Why did you apply for the Blue Oyster Caselberg Trust summer residency 2023?

I was actually invited by previous Blue Oyster director Hope Wilson to complete the residency, so I am very grateful to the trust and Blue Oyster for gifting me that opportunity and believing in my practice.

What did you want to achieve while based at the Caselberg Trust House and Charles Brasch Studio in Broad Bay?

Because there was almost a year between the residency and my exhibition I didn’t put too much pressure on myself to achieve any significant body of work, or have any solidified concept for the show. I wanted to just take it slow and let the work be informed by what was happening in the atmosphere.

How did you enjoy your time there?

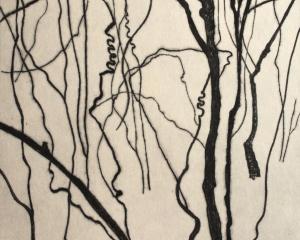

I had a lot of slow mornings, spending time with loved ones, swimming and walking, then I’d usually spend the afternoons drawing well into the evening.

What did it mean for your practice?

It meant so much. It really is the biggest gift you can give an artist, especially when there is no immediate pressure to produce something. I never usually have the time and space to draw. I find as a sculptor, drawing has become more of a planning space than an open one, so it was really nice to revisit some of my older modes of making and research through that medium.

How did you come up with the idea for the exhibition "Soda ash"?

Soda ash was born out of the very broad and relevant relationship between accumulation and disintegration, something building and weakening at the same time. This dichotomy is relevant to so many environmental and man-made processes that occur in and around the peninsula; starting from imagining Ōtepoti’s mammoth volcanoes; erupting and producing soft falling ash that accumulates back into its craters, forming a slow sedimentary build of earth; to the caves corroding along the coastline, filling themselves with tidewrack and anchored sea life, holding it together.

The properties of salt also corrode and build depending on the material it’s interacting with. The salt compound of soda ash is where the title comes from. Its original production was the result of burning sodium-rich plants and using the ash to slow down the melting point of sand to make glass and glaze for ceramics. I like the cyclical relationship it has with sea, earth, plants and fire and also its relationship with the surface of things, which is another important element to this exhibition. stormwater runoff became quite a focal point as I began to think more about the significance of my use of metals, seeds, debris and the weather. The permeable/impermeable tension around our built environments and infrastructure also played a big role in how I put my exhibition together.

How did the works develop from there?

I start any project quite intuitively. I find my material choices always make more sense the longer I hold on to them.

For this project my main material interests were metal and wood and how those two materials interact and affect their surrounding environments when exposed to the elements. Some of the work was only able to be completed during the install as there were some interventions we had to make with the building itself and some work was too fragile to transport, so I had to assemble them on-site. This meant there was no way of knowing how the work would react to the environment of the gallery, but meant the work was new to me as well as everybody else.

Describe the works in the exhibition.

The works consist of small constructions, alternative flooring, discrete work and architectural interventions. The forms they take describe a sort of amalgamation of different inlets/outlets and structures that make up various systems that operate in and around the harbour and peninsula. Processes like land stabilising, dredging, trapping and cultivating are all present within the works.

Some resemble construction and building supports - structures on their way to becoming something else; a kind of stalling, indecisive form that speaks to the many ways in which we interact with ecology and its inevitable force.

My material list is extensive, but include lots of the contaminants found in stormwater runoff - like heavy metals, sulphur, rubber etc.

I had help with a few of the works as they required some construction but mostly the works were all made with basic materials in my studio; glue, wire, tape etc.

You have had a busy few years of exhibitions -including "Central heating", Dunedin Public Art Gallery (2021); "heat transfers", Blue Oyster (2021); "Lay in Measures with Megan Brady", Enjoy Contemporary Art Space (2021); "Hush Swarms", Hot Lunch (2020); and "Console Whispers", Blue Oyster (2019) - so what drives you to continue making work?

It comes in waves. It depends on what opportunities are out there. I am constantly making work, but because my work is quite site-specific I do need space to respond to. I would like to eventually become less dependent on that though

How do you work?

I work a fulltime job, so even though it’s not ideal I work from my studio on Princes St in the evenings and on weekends.

Have you always been interested in art?

Probably when I was a teenager, I just found it relaxing. I never really had any big ideas about what I wanted to do with it, but knew I would probably always do it in some shape or form. My dad is creative. I’m not sure if he would admit to being an artist but he is. My granddad was an artist, too.

I did go straight to art school, which was incredibly liberating. I remember just thinking about how much easier it was than high school. I think I probably would have made better work if I’d gone a little later, as I had already finished my honours by the time I was 21 but I’m not sure if I would have had as much fun, so I think it was a good decision.

Why did you decide to follow the more sculptural side of making art?

When I entered second year of art school and we had to choose a medium to continue in. Sculpture seemed like the more open department that wasn’t specific to any material - it also had lots of stuff and interesting rooms.

Though I didn’t really end up using many of the facilities to make my work, I loved being around them. I’d spend a lot of time in the woodwork room, working with people’s offcuts and the same with the foundry. I also met my dearest friends through the sculpture department who had an immense influence on me. The lecturers and technicians (Scott, Jamie and Michelle) also had an impact on my decision to pursue this type of work.

It’s changed a lot really. I experimented with so much at art school (graduating from the Dunedin School of Art in 2017). I’d say it’s become more architectural, but in saying that, that’s because I’ve had the opportunity and support to achieve those things.

I think just having opportunities that give you a budget and technical support. I don’t think there has been any one moment that has been pivotal.

Who inspires your work?

Lots of things, but I’d say walking overall is the most important thing.

What do you do outside of your practice - does it influence your practice?

Yeah, I think anything I do influences my practice. It’s not easily identified where influence comes from.

Do you have another project on the go?

We are launching a photography publication that will sit adjacent to the show, with a text by Blue Oyster director Simon Palenski. There will also be a few public programmes that will be in support of the show.

TO SEE:

"Soda ash", Ed Ritchie, Blue Oyster Art Project Space, until February 24.