Debbie Neill

Life drawing has taken on a new dimension under the hands of Dunedin artist Debbie Neill.

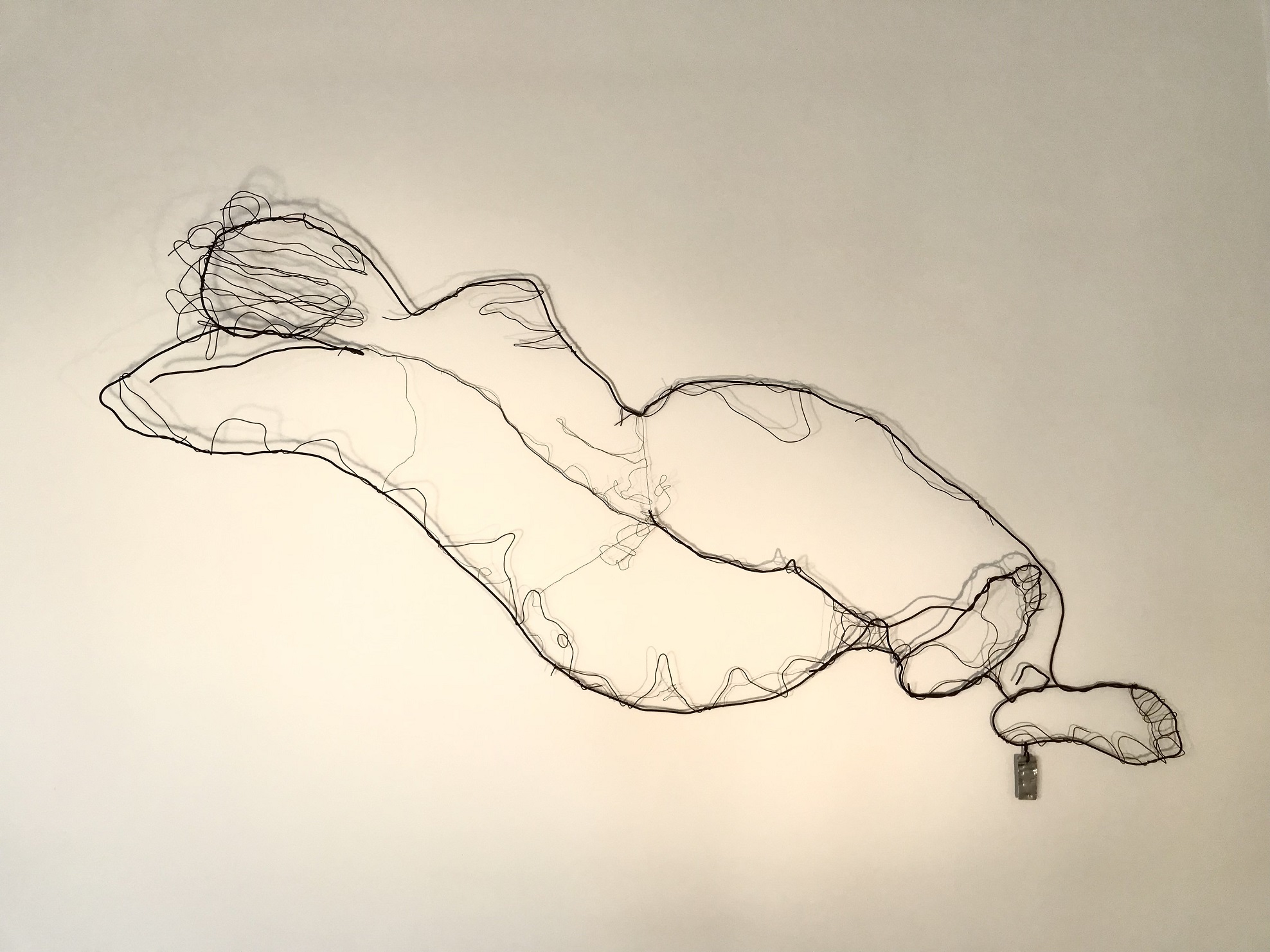

She uses redundant conduit wire pulled out of an old house to shape the female forms she has drawn, creating wall-hung sculptures.

"There is the juxtaposition of the soft form against the hardness of the material," Neill says of the two works which made the finals of the prestigious Parkin Drawing Prize, Evanescence IV-II and Evanescence XI-I.

Her two works, along with works by Glenorchy artist Emma Theyers and Dunedin artist Motoko Kikkawa, are among 76 finalists selected from 588 entries for the national drawing competition, which attracts a major prize of $25,000. Her work will be exhibited alongside that of other finalists at the New Zealand Academy of Fine Arts.

Even after having some time to absorb the news, she was still "blown away" by it.

It is especially sweet for Neill, a grandmother who has a masters in marine science and used to work in childrenswear retail and interior design, as she graduated from Dunedin School of Art last year, something she had wanted to do for many years.

She was always creative, often doing extra-mural courses in various things like ceramics, although it took 10 years to finish that course.

"I love it all."

She first did a certificate in creative studies in 2007 and applied for art school then, but other things got in the way — like travelling Australia’s field days with a caravan for nine months of the year selling battery additive.

"I was bored stiff but I said I’d do it for five years."

Neill knew that after that she would need to feed her soul by returning to art school, and she did so, but unfortunately her hoped-for return to the immersive environment of art school was stymied by Covid-19, forcing most of her study online.

However, it was Covid lockdowns that forced her to look for different materials to work with, as she could not take any clay work to a kiln.

"We’d just done a renovation and we had this bucket of old wire, so I decided to make bits and pieces out of it."

She started with a bird’s nest, as birds are her other passion — especially brightly-coloured Australian birds.

"I’m right into bird photography."

Challenged to push and explore different things by her lecturer, Neill started to make a dead bird out of wire, but it was only two-dimensional, so she tried making a three-dimensional bird.

Then she decided to bring together her love of life drawing with the wire work, creating the works she entered in the Parkin.

"They push the boundary of drawing."

The wire work is also quite hard on the hands as she bends and twists it into the shapes she is seeking.

"My hubby, bless his soul, strips the wire so I can use it."

She will use whatever length or width of wire she can find as it "creates the shadows and forms" of the life drawings.

"I don’t get too precious about it, or it doesn’t gel. I need to not think about it and just create."

The resulting sculptures are hung on the wall for her to "sit with" for a while so she can make sure they look complete.

"I also photograph it, as you can see then what is not quite right."

Neill has been life drawing for about 15 years, and uses actual life drawings as templates for her sculptures. The ones she drew for this project were done on 100-year-old wallpaper saved from her grandmother’s house.

"I love the family connections, the history and utilising resources like that. I put the wire drawing over the top. I’m a collector by heart."

She has never been one to make small works, and often bemuses her life drawing teachers with the large scale of her works, which are up to 2m wide, requiring her to jump from one end to the other to work on different aspects of the body.

"I’ve even had to devise a frame to put on the paper when I start drawing so I still have space to put the the arms and legs. When I first started off faces, hands and feet, they’re quite difficult and take time, so I’d leave them but then run out of space."

Every work she has done has been kept, so Neill can see the progress she has made over the years in the ways she makes her marks and the drawing process.

As life drawing sessions are often two hours long, they are exhausting, leaving her "absolutely shattered". For this project she did two two-hour sessions a day.

"By the end of the day I was knackered. But I thoroughly enjoy it."

She admits the models may recognise themselves in her wire works, as their forms are unique.

"I don’t see them as a person, I see them as a form, their lines and shape, not their nakednesss. You have permission to look without it being considered weird."

To her the female forms of her work are not about body image issues as such.

"They’re more about being comfortable with the inner self and reconnecting with who you are."

Having a science background, she finds it interesting that science allows people to study specimens all the time, but in art doing so is considered different.

Emma Theyers

Glenorchy artist Emma Theyers’ work is as detailed as Neill’s is large.

Her drawings of stones from Southland’s Riverton beach — Untitled, Riverton Stone 3 made the Parkin Awards final — in graphite and charcoal take many months to complete.

"This is a slow process of drawing the textured pattern in each stone to form a realistic representation. There is an interesting correlation between the time and labour invested in the drawing to the time implicit in the formation of such stones."

She is interested in the "aeons of time and amount of pressure" that occurs in this, the "seemingly magical", transformation process.

"These stones have been formed through erosion that takes place upon greywacke (argillaceous sandstone). Some New Zealand greywacke is over 300 million years old. "Transportation via rivers and the ocean has smoothed their surface, and in this case, exposed quartz lines, markers of pressure and time, in an exquisite geometrical pattern."

Each stone has a story to tell, the part-time gallery assistant says.

"They represent a depiction of life on Earth that no human can quite completely grasp. Their journey is monumental and ancient. My drawings aim to represent this intangibility through a dedicated depiction of a singular stone with which I place intense importance."

The medium she uses to draw the stones and the type of greywacke share similar qualities; both occur under pressure and take vast amounts of time to form, eventually eroding to leave behind their mark on material beauty.

"This is an important aspect of my current practice."

To make the finals of the awards is an honour, she says.

"Very excited. It’s a fantastic opportunity to launch and build my profile in New Zealand. I’m delighted to be placed within the context of ‘contemporary drawing’ here in New Zealand."

That is important as Theyers is a Covid refugee, returning from 20 years in Australia recently. While she was born in Clyde and grew up in Alexandra, she moved to Australia in 1998 after doing her first year of art training at the Dunedin School of Art. While in Australia she completed her undergraduate training at Griffith University, Queensland College of Art.

Drawing has always been an interest.

"I vividly remember being very excited about new colouring pencils as a child. My art teacher in high school was a very talented artist and I remember being in awe of his drawing skills. He encouraged me to go on and study art at university level. I think this was the point I began to consider art as a viable career."

She has kept drawing over the years, sometimes as a full-time artist and at other times part-time. Drawing is the most effective approach for enabling her to get the detail and realistic representation she seeks.

"I’ve recently begun experimenting with different surfaces; cement fibre board [industrial product], schist stone and more recently a paper made from recycled stone (karst paper).

"The drawing of stones has been a dedicated project and an ongoing motif in my practice. I find it incredibly potent subject matter."

Her interest in stones was initially inspired by a personal interest in Buddhism and Zen gardens.

"I’m curious that there could be a correlation between the potency of Zen gardens, and geological motifs, I experienced in Japan, to that of the geological matter here in the South Island.

" I think there is an implicit energy in my subject matter. I’m essentially investigating the possibility of achieving a transference of this energy to the drawing itself. It’s my intention for the viewer to experience this type of energy."

In Australia, she exhibited in Queensland and New South Wales and was a finalist for many prizes, including the JADA Drawing Prize, Hadley’s Landscape Art Prize and the Dobell Drawing Prize.

"A recent highlight was exhibiting here locally as part of the group exhibition ‘Stoned’ at Broker Gallery, in Queenstown."

Finding different types of stones to draw takes significant time, as each region can have a lot of variation even within a few kilometres.

"I find this fascinating. It’s a great way to get to know my home country again and spend time in nature. I spend a lot of time refining my selection before choosing a specific stone."

She then takes many photographs over days, testing angles, lighting and shadows.

"Stones are an impressive piece of phenomena so it’s essential to find the best possible option to express this monumentality."

Theyers uses mostly charcoal and graphite in both solid and powder form, and sometimes a brush to build layers.

For her piece in the Parkin Prize, she prepared cement fibre with a layer of charcoal and graphite in order to create the texture of stone, then removed the charcoal with an electric eraser, one dot at a time.

"This is a very intimate way to learn about their formation. In a sense it can be likened to drawing individual particles within the stone. The fine detail in which I represent each stone is contrasted with marks from broken charcoal that naturally falls on to the drawing surface and other smears caused by my hands and forearms as I lean into each piece."

After so long in Australian cities she is enjoying living in Glenorchy, being near family and immersed in nature and close to the mountains.

"It just felt like it was time to re-establish my connection with New Zealand."

Motoko Kikkawa

Dunedin artist Motoko Kikkawa has made the finals of the Parkin for the third time, this time with Weathers, a "doodle" inspired work on paper using mechanical and cold pencils.

"I always love looking at someone’s doodle. Even my own one, especially after long talking on telephone.

"Often I see shapes I’ve never seen before. So I decided on making a serious doodle."

The work took more than six months, as her neck or back started to ache after a couple of hours drawing each day.

"To concentrate on, I listen to life counselling on YouTube. It is very comfortable, specially the feeling of paper, and hard to stop ."

"I thought it’s like weathers on Earth."

The finalists were selected by an advisory panel, consisting of leading painter John Walsh, contemporary ceramics artist Virginia Leonard, and artist Matt Gauldie.

The works will be showcased at the Parkin Drawing Prize exhibition at the NZ Academy of Fine Arts in Wellington, and the winner will be announced at a gala on August 1.

To see:

Parkin Drawing Prize exhibition at the NZ Academy of Fine Arts (August 2–September 11)