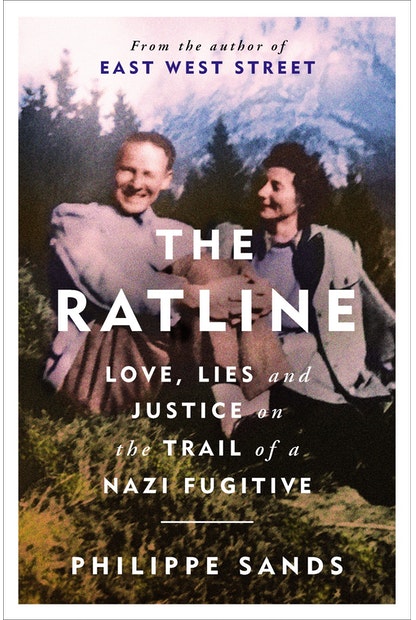

THE RATLINE: LOVE, LIES AND JUSTICE ON THE TRIAL OF A NAZI FUGITIVE

Philippe Sands

Weidenfeld & Nicolson

By JESSIE NEILSON

‘‘My father was a real, great figure, not just an SS man, running around shooting, killing people,’’ insists Otto von Waechter's son and stalwart apologist, Horst.

The Austrian fascist and Obersturmfuehrer, more accurately regarded as the Butcher of Lemberg, was apparently above all ‘‘kind’’ and ‘‘humane’’ and governed with love, only participating in and sanctioning mass murder of Jews and local Poles at great reluctance.

According to his ever-loyal wife Charlotte, he was a ‘‘sensitive, joyful, optimistic life personified’’, and despite being a womaniser he provided her with a luxurious lifestyle, in homes appropriated from Jewish families, while at the same time instigating the Krakow Ghetto, where, under his watch, over half a million people were murdered. Painful parallels are set up between Charlotte's wilful obliviousness as she bemoans the odd inconvenience in her own life, which is accompanied by maids and freedom in the great outdoors, to nearby cramped torment.

The ratline refers to the ‘‘Reich migratory routes’’ by which Nazis escaped post-war, mainly to Latin American countries. This was often aided and abetted by the Vatican. Von Waechter spent years fleeing, but locally. He was highly ambitious, calculating, and likeable to his kin, and had risen quickly through Nazi ranks to become Governor of the Nazi-occupied Krakow district, and later Governor of the District of Galicia, the capital of which was Lemberg. At various times also known as Lviv, Lwow, or Lvov, Lemberg had been a regional capital of the Austro-Hungarian empire and today, as Lviv, is a city in Ukraine.

Author Philippe Sands, a British-French lawyer with a keen interest personally and historically in this region's brutal past, focused on this area too in his 2016 book East West Street, which won the Baillie Gifford Prize for Nonfiction, among others. He has published prolifically and was due to speak in person at this year's Auckland Writers Festival.

Sands' captivating prior work traced his grandfather Leon Buchholz's rise and fall as a Jew at the same time as fellow Lvov-based contemporaries and Jews, Hersch Lauterpacht and Raphael Lemkin, were developing their concepts of crimes against humanity and genocide respectively. These terms would be used for the first time following World War 2, in the Nuremberg Trials, to hold criminals accountable as individuals, rather than as actors of a greater agent.

Also featuring prominently was Hans Frank. Through the 1940s he had been governor general of Nazi-occupied Poland, responsible for setting up the concentration camps and the following 4 million deaths. He was also Hitler's lawyer. Von Waechter reported directly to Frank. The former's earlier deeds included his part in assassinating the Austrian chancellor in 1934 in an unsuccessful putsch, as well as authorising a later reprisal of Poles, the first such act in Poland. He enforced the Star of David decree in his region, and ended the careers of thousands, including two of his university professors.

From early days he spent his life running and hiding. Thus son Horst, born 1939, says he hardly knew his father, but it is for the love of his mother that he protects his father's reputation of ostensible innocence above all else.

Sands was introduced to Horst through their mutual acquaintance and, astoundingly, Horst's close friend, Niklas Frank, son of Hans. Unlike Horst who refuses to engage critically with his father's atrocities, Niklas abhors his own father's legacy, carrying around in his wallet a photograph of him post-mortem, from his execution by hanging. While he does not believe in the death penalty, he would gladly make an exception in the case of his father.

Niklas has dedicated his life to educating people on the depravity of his father's regime, whereas Horst bides his time trying to convince people that his father was a specimen most ethically correct. And while Horst's father's death in 1949 was deemed natural, Horst seeks out conspiracies. Together he and Sands investigate, using in part Charlotte's extensive photographs, diaries and letters, which run to more than 8500 pages.

Like East West Street, this story is fascinating and complex, in no small part due to the apparently huge likability, as well as absolute delusion, of one Nazi's son. Horst and the author would conduct interviews in Horst's baroque castle at Hagenberg, bought with family money. Photos of his dead Nazi relatives and godfather Arthur Seyss-Inquart grace the walls.

The legacy of such actions has consumed Horst and the author's lives in quite different ways. Both have been involved in documentaries around this as they seek justification. What is remarkable is the extent of Horst's denial: an utter refusal to acknowledge his father's instigation of wreckage, torture and mass murder.

Jessie Neilson is a University of Otago library assistant