About a third of Dunedin Botanic Garden is bush, covering 11.5ha of the 33ha garden.

Surprisingly, it needs to be actively managed. It’s part of the Dunedin Town Belt, has been highly modified and needs a helping hand to guide it into a long-lasting healthy future.

This forest is at a crossroads. If left alone, pest plants would spread, resulting in swathes of sycamore, old man’s beard and other pest plants. Instead, this forest is being nudged down another path towards regenerating and becoming healthy and strong.

Since Pakeha settlement, timber has been removed from the town belt and it has been grazed and cleared for private use. In 1874, a councillor proposed to sell off sections of the town belt for building. Fortunately, the council rejected the motion.

Counter-intuitively, history’s random approach to town belt conservation benefits today’s Dunedin Botanic Garden. In 1869, the sunny, sheltered area previously occupied by the Acclimatisation Society became the new site for the botanic garden when it was transplanted from its old site at the University of Otago.

The result of history’s affronts is that most of the garden’s bush is small, fragmented remnants of regrowth. This means lots of unprotected edges vulnerable to wind penetration and invasion by pest plants and animals.

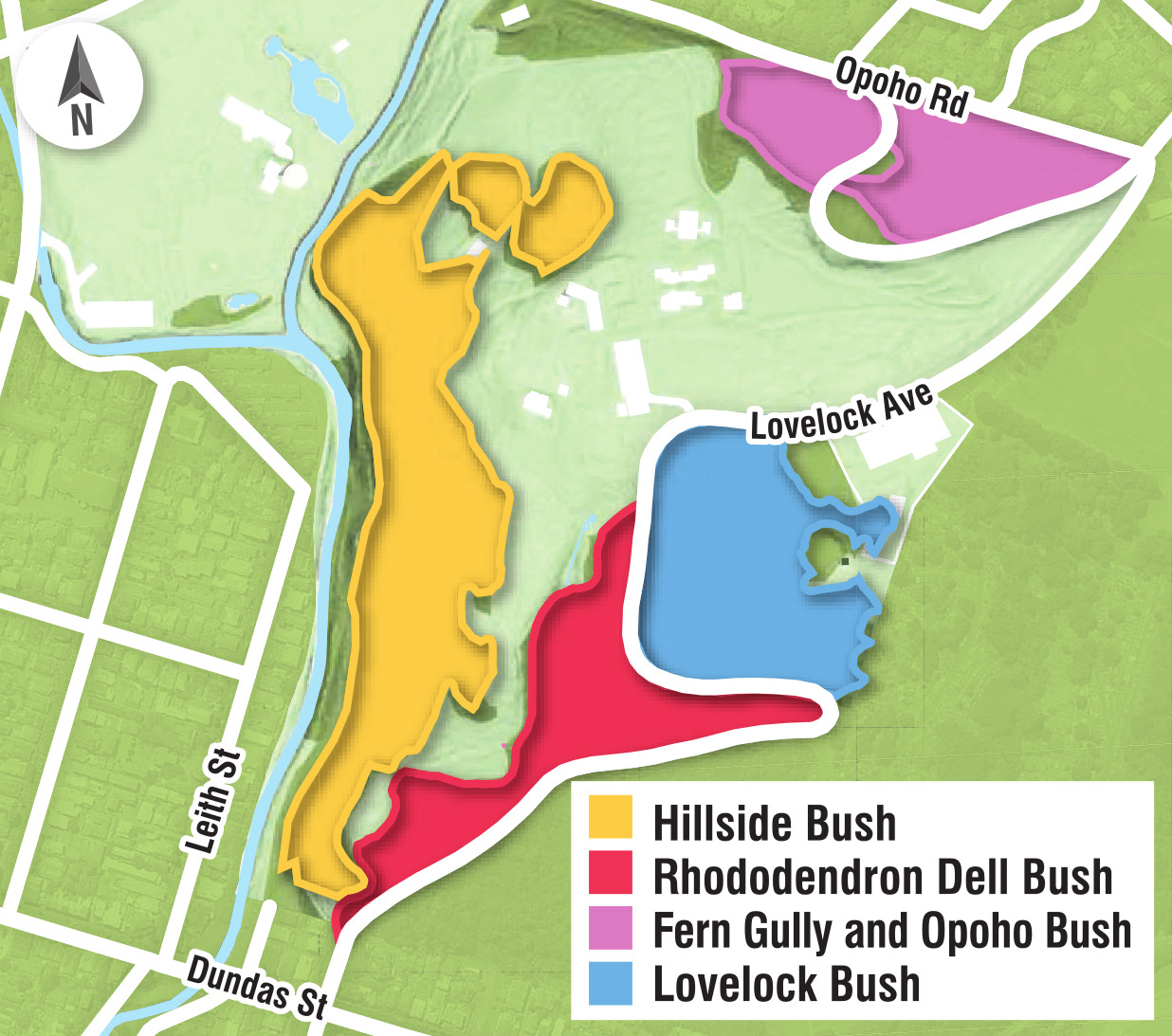

A chunk of bush at the east end of the garden is separated by Opoho Rd. Fern Gully has a creek, and a deep humus layer and diverse vegetation support many birds including native brown creepers. Despite its idyllic name, ferns in the gully aren’t all benign natives — an invasive Dryopteris is spreading, leaving less room for the locals.

Hillside Bush has slopes so steep that staff would need to be harnessed to climb some of them. One part is 55 degrees. This means erosion by water and barely any leaf litter or soil. Pest plants and birds live here but, on the flip side, few pest animals.

Lovelock Bush is open and provides plenty of space for gutsy rodents. It is the busiest area in the garden for rats and mice.

The Rhododendron Dell bush surrounds and covers a sheltered gully. It’s healthy with lots of invertebrates and birds, making it a magnet for pest animals.

Standing at the bottom of the dark gully near Lovelock Ave, this broadleaf was once surrounded by pristine original native forest. Even our most treasured historic buildings weren’t built when it was in its youth. What lush birdlife did it see? Now it witnesses the sounds of passing cars and planes.

Its age means it’s a local ecotype with genes adapted to local conditions. Its younger neighbours might be too, if they’ve descended from local plants, but with plant introductions by humans over the years, there’s no guarantee any of the younger native bush is truly local in origin.

The broadleaf’s known provenance makes it an ecological taonga. Cuttings have been taken and seedlings planted in the bush pocket by the species bed of the dell.

Broadleaf is also known as the "ice cream plant" because of its appeal to introduced browsing animals. Native and exotic trees and the cultivated plant collections are vulnerable to browsers’ teeth.

To manage browsing damage, since 2007 contractors have been brought in a few nights a year to shoot possums and rabbits. Most animals have been found in the dell bush.

An average of 25 possums a year have been killed throughout the garden, but there hasn’t been a distinct pattern in numbers as the programme has varied each year. It’s been a help, but a drop in the ocean, although now a brilliant new initiative is about to take off.

City Sanctuary is a council-managed project that implements community-led predator control in backyards and reserves. It’s the urban arm of Predator Free Dunedin, the conservation collective aiming to get rid of possums, rats and stoats from Dunedin and environs by 2050, the Government’s aspirational date.

More than 50 permanent traps have just been laid, encircling and criss-crossing the garden. They’re baited and mounted to be safe for domestic pets. They’re not in areas of high use by people, but will be highly attractive to possums, rodents and stoats. Monitoring lines have also been established to monitor the effectiveness of this new control approach.

This means big gains for the bush and plant collections. Permanent traps mean a consistent, intensified level of control to suppress animal numbers as opposed to the spikes of the shooting programme.

For the wider predator control programme, the addition of the botanic garden plugs the gap between the town belt and Signal Hill. The garden now plays its part in the network of protected areas that are helping our forest to grow naturally.

City Sanctuary will train volunteers to manage the botanic garden traplines. It involves a one-hour loop walk on set days and times, with a year-long commitment by each volunteer. People have already signed up, but there’s room for more. If you’re interested in volunteering, contact info@citysanctuary.nz.

The introduction of trapping times perfectly with the garden’s intensified effort to blitz the other threat to bush conservation, pest plants.

Like others throughout the country, Dunedin Botanic Garden was founded on the Victorian horticulture model that valued the display of plants for their aesthetic value. This meant the garden’s focus was managing the cultivated plant collections.

Now the ecological movement has raised awareness of the conservation responsibilities that come with being kaitiaki of bush and land which will last in perpetuity, maybe longer than the botanic garden.

As a result, pest plant control has cranked up in the past 20 or so years. Task Force Green workers dedicated themselves to removing some of the worst offenders. Carpets of ivy they literally rolled up more than 15 years ago have left a clear understorey now being populated with native ferns.

Community group volunteers then supplemented this effort during one-off weeding days, attacking aluminium weed and hypericum. Both are insistent invaders and soon grew back.

Pest plants and animals

In 2015 and 2016, Dutch interns studied the bush for six months and filed some eye-opening reports. The extent of the problem fuelled a more targeted approach beginning in 2017. That winter, all gardening staff dedicated every Wednesday for 11 weeks to hand sawing and grubbing their way through the 15 most troublesome weeds. Throughout June, July and August this year, staff worked on pest plants for two mornings a week.

Camellia collection curator Marianne Groothuis said “the result was incredible”. The forest floor was freed for native plants to have a chance to grow instead of the aggressive exotics getting in first.

Now every area of the bush, except the steepest slopes, has been targeted. Resurging pest plants are being knocked out and there is less regrowth. Harmless plants are left to rot and leave their nutrients as fuel for the forest.

Sycamore is also being controlled. Staff attack seedlings that pop up, but some mature trees on steep slopes can’t be felled. Instead, they’re ring-barked using the herbicide DOC uses for wilding pines, X-tree Basal Wet & Dry.

This spring is the third year of the sycamore programme. A contractor sprays the base of large, grandparent sycamores and some require two applications. Small branches decay first then the tree slowly falls down to decay on the bank beneath. Sycamores are fast-growing and easily win the race for space on the forest floor. Removal of their large ongoing seed sources is a no-brainer.

Pest plant control is hard physical work but the investment the garden is making is already showing results and will pay dividends for hundreds of years.

Rhododendron Dell curator Doug Thomson said is was really satisfying.

“It’s rewarding when you hear comments from people who notice the change.”

The animal control work is adding to the bush’s arsenal, eventually returning it to its natural ability to live long and prosper.

- Clare Fraser