It was dubbed ‘‘Mission Impossible’’ - set up three huts in a day on a beach in the Antarctic notorious for having some of the worst weather in the world. Guy Williams talked to ‘‘Turk’’ designer Erik Bradshaw about his two-week adventure on the ice.

Arrowtown adventurer Erik Bradshaw had a bright idea last year - get a plastic water tank and build a lightweight but tough alpine hut.

He built it in his backyard with some mates, and had it flown into the hills for use as a backcountry skiing and tramping shelter.

On February 7, only a year after his light-bulb moment, he found himself in a Boeing C17 jet, bound for the Antarctic, with a slightly bigger project on his hands.

It was to install three of the huts at Cape Adare, 700km north of New Zealand's Scott Base - a desolate spot exposed year round to freezing winds from the continent's interior.

Sitting with him on the plane were three Antarctic veterans: Queenstown builder Doug Henderson, engineer and mechanic Jeff Rawson and Department of Conservation backcountry construction specialist John Taylor.

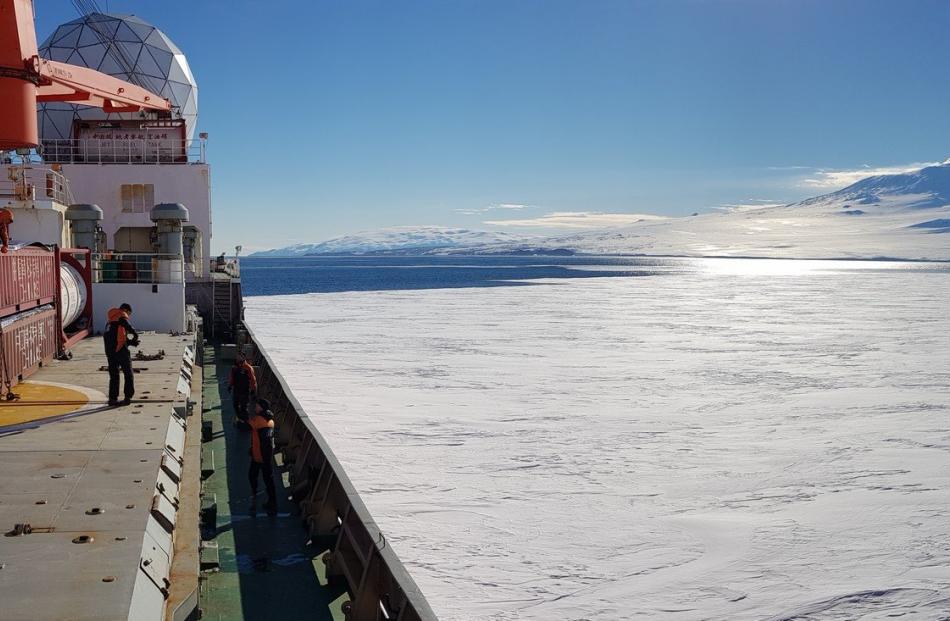

Waiting for them on Chinese icebreaker Xue Long in McMurdo Sound were the huts, built by Mr Bradshaw and a small team in Lyttelton late last year.

They had been ordered by Antarctica New Zealand for use in a project to conserve the first building ever erected on the continent.

From next January, a seven-strong Antarctic Heritage Trust team will spend a month at Cape Adare, in each of the next four summers, working on the hut of pioneering Norwegian explorer Carsten Borchgrevink.

On February 12, three days after Mr Bradshaw and the team reunited with Xue Long, the icebreaker arrived at the Cape.

He said they struck one of its few fine days a year, with little wind and a temperature of about -4degC.

In another stroke of luck, preparatory discussions with the leaders of the Chinese expedition on board the ship produced an unexpected boost in manpower.

''We had asked the Chinese for four people to help us set up the huts,'' Mr Bradshaw said.

''They discussed it, looked at their timeframes, and said 'we can do this, but we want to use 50 people'.

''So we said OK.''

In what he described as ''probably the most planned day of my life'', onboard preparations began at 6am.

By noon, everything was ready to start work on the beach. The local inhabitants - the world's largest Adelie penguin rookery - watched as the three 10sqm huts were lifted off the ship by a giant Russian-made helicopter.

The job was completed by 9.30pm, in the polar twilight, in half the time they had budgeted for.

Mr Bradshaw put that down to the fine weather and the sheer manpower at their disposal.

The four New Zealanders would have ''absolutely exhausted ourselves'' without the help of the assortment of Chinese crew members, builders and scientists.

Despite minutely detailed planning, they had underestimated the difficulty of moving 19 tonnes of gravel in wheelbarrows for placing in the huts' bases to anchor them to the ground.

The beach was softer and steeper than expected, making it a tough job for only eight people.

''That probably tripled the effort required. We would've run out of time and had to leave things in quite an incomplete state.''

The Chinese were ''incredibly cheerful, positive people'' to work with, and effective at working as a team.

''They wanted to make this work, because they really value the relationship with New Zealand.''

The huts will sit empty until next January, when the conservation team arrives for its first stint.

They had to be installed this month, to avoid the Adelie penguin breeding season in November-December but before the coming polar winter.

Mr Bradshaw said he was confident the conservators would like what they saw when they walked into the huts next year.

''I think they'll be really happy. Compared with staying in a canvas tent, it's complete luxury.''

Antarctica New Zealand had expressed interest in using more of the huts for some of its other projects and research sites.

They were a low-cost, quick-to-assemble, highly effective form of accommodation, he said.

''They've being trying for five years to get something into Cape Adare, and so we finally nailed it.

''It's definitely a design in a state of evolution, and there's a lot of things I'm still working on in refining and improving them.

''Having said that, I'm still very confident that what we built will survive the lifetime of the occupancy of them.''

Cape Adare

Carsten Borchgrevink made one of the "great Antarctic mistakes'' by choosing Cape Adare as the base for his 1899 expedition, and now Mr Bradshaw understands why.

The Anglo-Norwegian explorer was a member of a whaling party that made the first documented landing on the Antarctic mainland, on the Cape's beach, in 1895.

Based on the fine weather he experienced that day, he chose the beach as the base for his 1899 expedition, the first to spend a winter on the continent.

It proved a terrible choice, Mr Bradshaw said.

"He had gone there and had one of the few perfect days in a year, like we had. Then he went back there to winter over and had an absolutely miserable time.''

Fact box: Cape Adare tank huts

• One is a living space, the second a workshop and the third a store room with a toilet cubicle

• Each has a door, windows and internal joinery

• Waterproof and highly insulated

• They are strong enough to withstand temperatures of -30degC and 200kmh-plus winds

• Dubbed "Turks'' because they are somewhere between a tank, a hut and the yurts traditionally used by Central Asian nomads