Artificial intelligence is transforming life in New Zealand more quickly than many realise, states a new report from the Royal Society. The urgent task is to ensure it helps more than it harms, writes Bruce Munro.

The future is ready to talk to you - so long as you are the leader of a global brand or business.

Talk to you properly, that is.

We can all have conversations with machines. We can talk to our phones and get verbal responses. Our banks and government departments often prefer us to answer machine-driven questions rather than talk to a real person. Increasing numbers of business websites offer to answer queries using online chatbots - computer programs written to do a half-decent job of responding to questions in full, if somewhat stilted, scripted, sentences.

But if you want to engage in conversation with a robot that meshes advanced artificial intelligence (AI) with hyper-realistic animation - a machine that can perform intellectual tasks as capably as any human, can evolve over time and operate autonomously with a full range of emotions - then you need to talk to Sam.

Sam is the future of AI, now. She, and her siblings, are the online, living, not quite breathing, brainchildren of New Zealand-based company Soul Machines, which says it has created "the world's most human digital beings''.

But to talk to Sam, you need to apply. And to apply, you need to be Someone. Because, according to the website,"Sam is conducting meetings exclusively with leading brands and business globally''.

Undoubtedly, that is because Soul Machines' founders see Sam's potential as "the first fully autonomous digital influencer capable of interacting as a human would but with the control brands need and expect''.

Sam might be the first. She is certainly only the beginning.

Chatbots and digital puppets achieve what is defined as Level 1 autonomy - basic and rudimentary autonomous behaviour. Soul Machines is aiming for Level 5, the holy grail of AI - full agency with self-awareness.

On its way there, Soul Machines has created Lia, a digital human brought to life for the Royal Society Te Aparangi. The occasion of her arrival is this week's release of the Royal Society's report on the future of AI in New Zealand.

Supporting the digital paper copy of The Age of Artificial Intelligence in Aotearoa, Lia, in four online videos, outlines what AI is, how AI is and will be used, and some of the concerns real humans have with Lia and her kind.

"Hi there. I'm Lia,'' she tells viewers.

"My digital brain allows me to sense, learn, make decisions and communicate in real time, just like you.

"People may have concerns that digital employees are going to take over their jobs. But, alternatively, we could work alongside you, complementing the tasks you do in order to achieve better results.''

For many people, however, the learning, let alone the trusting, is still to happen.

There is a widespread feeling that the potential achievements and gains offered by AI make its advance unstoppable. There are suggestions it is already proceeding at pace and that the effects could be as transformative as the advent of mechanical machinery, which totally reorganised the landscape and society 250 years ago. There are also muttered dire warnings of AI's latent destructive power and the havoc it could wreak.

Which is why the Royal Society has produced its report.

"There are many commentators making predictions or issuing warnings about possible consequences, but we don't yet know how important some of these benefits or detriments will be,'' the report states.

"However, we can confidently say that the implementation of AI is moving at a far greater pace, and is immediately global, in a way that the first industrial revolution was not.

"We all need to have some awareness and understanding of AI to ensure it is managed wisely and we are able to maximise the benefits of this technology for all.''

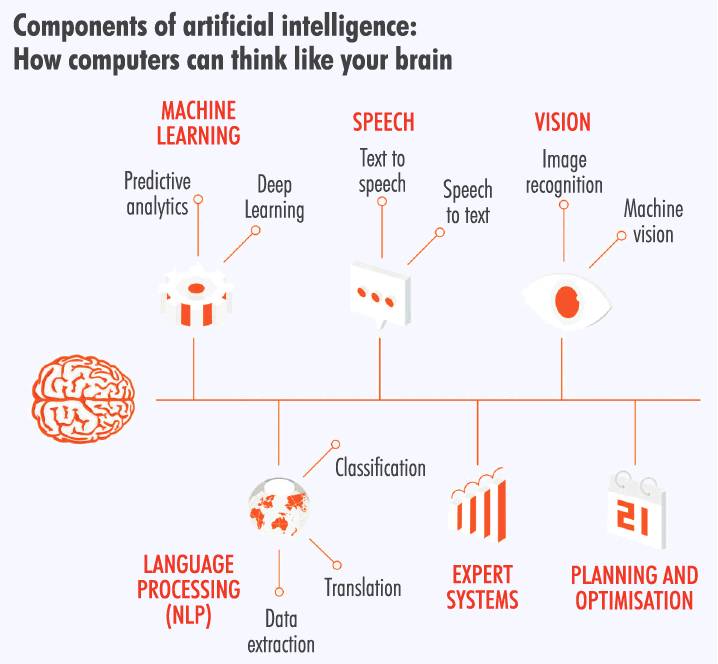

THE starting point for understanding AI is realising it is not a specific technology, the report says. Rather, AI is a term to describe a wide range of new computer methods and techniques to solve problems, make decisions and perform tasks that would otherwise require human thought. AI is computers doing human thinking.

What is helping AI develop is the growth of three technologies - data storage, computer processing and the internet. The convergence of big data, fast processing and wide connectivity is enabling computers to become more human-like, to think much faster than humans and to weigh options.

AI loves nothing more than to chew through big chunks of information, such as medical files, census information and the endless streams of data from social media. Computers can be programmed to study this data, learn from it and make predictions, Prof James Maclaurin says.

Prof Maclaurin is co-director of the Centre for Artificial Intelligence and Public Policy, at the University of Otago. He is also one of the authors of a report by the Australian Council of Learned Academies (ACOLA), The Effective and Ethical Development of Artificial Intelligence: An Opportunity to Improve Our Wellbeing, to which New Zealand has contributed. The Royal Society report has come out of the ACOLA project.

"AI is good for processing information faster in order to select and weigh options more efficiently or to identify connections that were not obvious before,'' Prof Maclaurin says.

But, he adds, people still have to tell the computers what questions to ask and have to program them in a way that will give useful answers.

The Royal Society report says the rise of AI does not mean computers will begin to think for themselves, although it concedes philosophers, biologists and computer scientists are debating whether it is possible. Groups such as Soul Machines clearly think robots that can make their own free choices and act independently are not just a possibility but the goal.

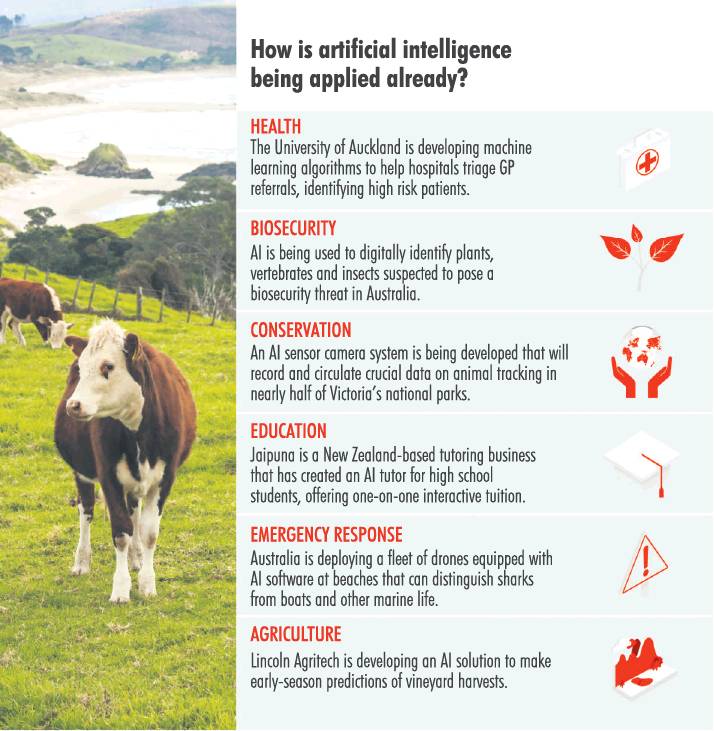

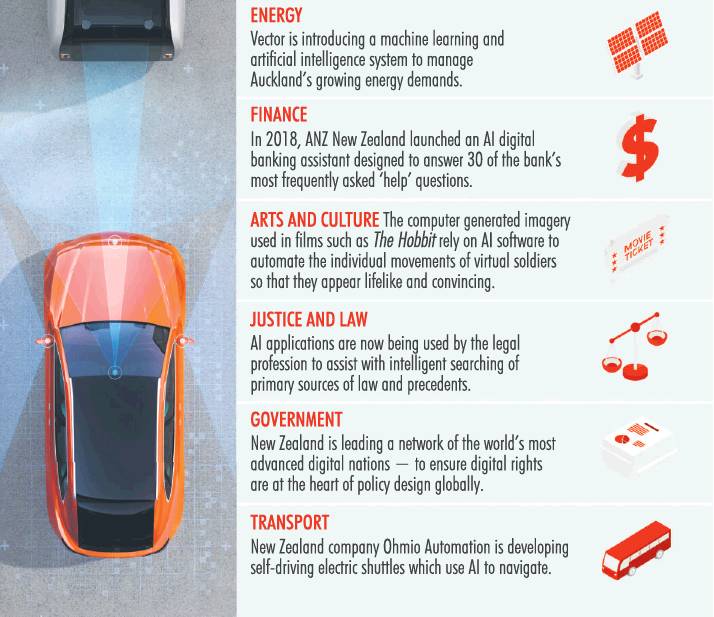

The Age of Artificial Intelligence highlights how AI is already helping in areas as varied as finance, the arts, health and education.

AI-empowered banking systems monitor transactions and alert customers if something seems unusual, such as an atypical payment to an overseas company.

Computer-generated imagery used in blockbuster movies often relies on AI software to, for example, automate the movements of hundreds of virtual soldiers fighting in a virtual battle so they all appear life-like.

AI is helping doctors choose the right cancer drug treatments for patients from the hundreds of drugs available. Other AI technologies are being used to rehabilitate stroke sufferers and can interact directly with the brain to enable people to control artificial limbs and even robotic exoskeletons.

In education, Jaipuna, for example, is a New Zealand-based tutoring business that has created an AI tutor, offering one-on-one interactive tuition to high school pupils.

The use of AI in New Zealand will only increase, the report says.

The University of Auckland is developing machine learning algorithms to help hospitals triage patients, identifying those at high risk.

Potentially, AI could also diagnose illnesses, providing support and backup for GPs and giving them more time to focus on the patient.

Energy company Vector is introducing a machine-learning and AI system to manage Auckland's growing energy demands.

Lincoln Agritech is developing an AI solution to make early-season predictions of vineyard harvests.

Wireless cattle collars are being developed that gather information on an animal's location and behaviour, to help farmers make better decisions about grazing management, feed supply and when to muster.

It has been estimated that next year worldwide revenues from the adoption of AI systems across multiple industries will be more than US$47 billion (NZ$73.4 billion), compared with US$8 billion just four years ago.

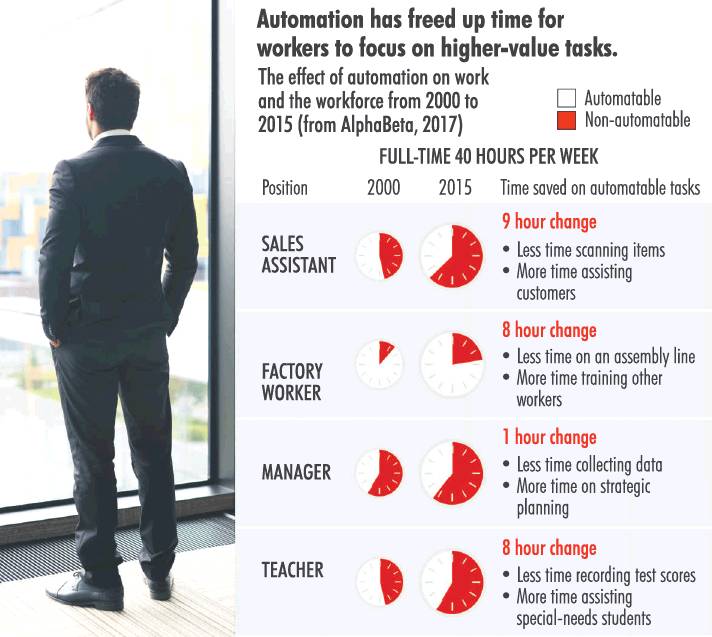

It is clear AI is becomingly increasingly ubiquitous. Less certain, is what that means for the jobs humans do, the Royal Society says.

It is likely that few existing occupations will remain untouched by AI. Since the new millennium, the average worker has already had two hours per week of their routine, predictable tasks automated. By 2030, that will be four hours.

"So, while AI might not take your job, it is likely to affect what you do,'' the report says.

"Career flexibility, continuing professional development and training will be important.''

The Royal Society report raises important concerns and questions about AI's impact.

AI needs large amounts of information. It can hoover up that data from multiple sources. But that can present technical and legal quandaries related to privacy, anonymity and tracing the origin of information.

Systems are only as good as the data they are built on. Biases in the data can produce spurious but plausible predictions, which may not, in fact, reflect the real world, the report warns.

AI relies on computing hardware that uses materials that are rare and finite, and their disposal presents a waste management challenge. The contribution of computers and smartphones to global greenhouse emissions is currently on a par with air travel, about 8% each.

Increasingly, AI is being integrated into military and security systems, creating ethical questions about the decision-making of AI-controlled weapons.

How will we prevent our genetic information, health history and online activity being used to discriminate against us in employment and insurance?

Could we become too dependent on AI doing our thinking for us?

Could AI get out of control?

The urgent task is to ensure AI helps more than it harms.

That is also the view of Dr Benjamin Liu, a senior lecturer in the department of commercial law, University of Auckland.

Dr Liu, commenting recently on the high-level of AI use by government departments in New Zealand, said the legal and policy issues of AI are becoming increasingly pressing.

"Take facial recognition as an example. [Recently] San Francisco banned local law enforcement ... use [of] facial recognition. [And], an office worker in the UK launched the first legal challenge over police use of surveillance equipment because his picture was taken while shopping,'' Dr Liu said.

While AI technologies raise difficult legal and ethical questions, we must not forget the huge potential AI can offer, he says.

"For example, police in New Delhi recovered 3000 missing children within just four days after using facial recognition software. And back home, we all enjoy the convenience brought by eGate when we pass through Auckland International Airport.

"In the end, the key question is not about whether to use or ban AI, but rather how to preserve the fundamental values we share in our society.''

Assoc Prof David Parry, head of the computer science department, AUT, says a scientific and inclusive approach is needed.

"Only open, well-designed trials will allow a true assessment of the value of these systems,'' Prof Parry, commenting recently on the errors that can creep into AI systems, said.

"They cannot be assessed effectively by simply being inspected and complying with a set of pre-existing rules.

"A suitable regulator would behave like a medicines agency, requiring proof that the algorithm is effective from independent studies, proof that it is being used correctly, and surveillance of outcomes along with the right to stop an algorithm being used.''

Prof Maclaurin says it is important AI benefits everyone, not just a small number of companies or a small proportion of New Zealand's population.

"As a country, we need to figure out the regulatory requirements that would provide assurance of safe and just use of artificial intelligence.

"The decisions we make now will determine our future, which is where human intelligence comes in. We have the opportunity to set a global example for responsible adoption of AI. With proper oversight, AI has the potential to enhance wellbeing and provide a range of benefits to all New Zealanders.''

It sounds a lot like digital human Lia on the Royal Society videos.

"It's great that you are learning more about us ... as it ensures that you trust us to help each and every New Zealander thrive in the Age of Artificial Intelligence.''

Who had that thought first is unclear.

For more

To find the Royal Society report The Age of Artificial Intelligence in Aotearoa and the videos of digital human Lia, go online to https://royalsociety.org.nz/major-issues-and-projects/ai/