It might be time for plastic shaming, Dr Sommer Kapitan thinks.

"Plastic use is becoming a moral issue. Like cigarette smoking once was," the senior lecturer at Auckland University of Technology said this week, responding to a new Royal Society Te Aparangi report on plastic.

Plastics in the Environment: Te Ao Hurihuri - The Changing World confirms that plastic is everywhere now. In the air we breathe, in the deepest oceans, in the water we drink.

It chokes the life from birds and marine life. It changes soil chemistry. As it breaks down, it leaches toxins.

We have discarded three quarters of the volume of plastics ever produced.

"This amounts to hundreds of millions of tonnes of plastics being disposed of as waste every year," the report says.

At this point then, "Carrying and using plastic should become as objectively gross as blowing smoke in a baby's face. We should all be outraged," Dr Kapitan says.

But she acknowledges it is not an easy fix.

Plastic has become ubiquitous.

Royal Society Te Aparangi president Prof Wendy Larner points out that it is now present in everything from "construction to clothing, food distribution and healthcare".

And as the quantity of plastic used and consumed soars inexorably - the amount produced each year has doubled in the past 20 years and is still growing rapidly - those committed to addressing the mounting waste problem say we must look for new solutions.

Just this week community enterprise Wastebusters has announced it is reducing the range of plastic containers and bottles it accepts for recycling in Wanaka and Central Otago. From August 1 it will accept only numbers 1, 2 and 5 plastics after markets for other plastics collapsed. It will now concentrate on those plastics that can be recycled in New Zealand.

Wastebusters recycling manager Bis Bisson says the policy reflects the reality of today's recycling world, and Wastebusters' desire to be upfront with their customers and to encourage more transparency in the recycling industry.

"Since China stopped taking plastics for recycling under its `National Sword' policy, we haven't had anywhere globally to send mixed bales of 3-7s for recycling. Plastics 3, 4, 6 and 7 make up a small fraction of the recycling we collect, and with no way to reprocess them we've made the decision to stop collecting them."

Organisations such as Wastebusters are at the unenviable end of a tide of plastic consumption.

New Zealand is a high per-capita user and, like the rest of the world, produces large amounts of plastic pollution, the Royal Society report says.

The US tops the chart in terms of daily plastic waste at 286g per person per day. Germany and the UK are close behind. But New Zealand is right up there at 159g, well ahead of the likes of the Scandinavians, at about 30g.

We produce more than a kilogram each every week here in Godzone and our bodyweight every year or 18 months.

Kiwis use about 295 million disposable cups a year.

In 2017, New Zealand imported more than 300 thousand tonnes of plastic resin. Then there's textile imports, 49% (by value) were plastic. That year we exported 41,500 tonnes of plastics as waste.

Less than 20% of the waste plastic generated each year is recycled worldwide. Of the remainder about 70% goes to landfill and 30% is incinerated. Recent estimates are that, globally, up to 600 million plastic bags and 60 million bottles are used every hour.

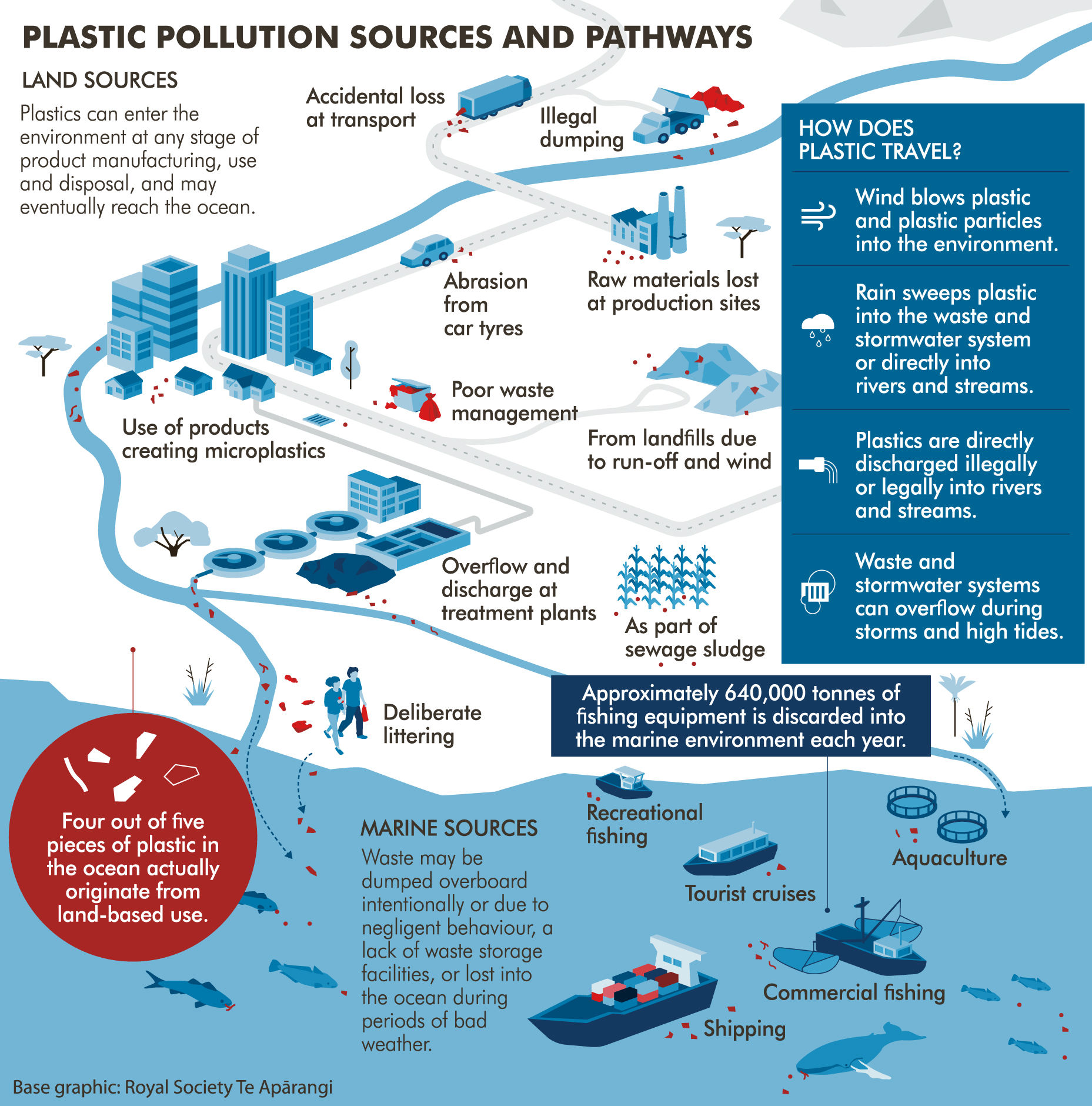

When not recycled or carefully disposed of in landfill, waste plastics linger in the environment, Plastics in the Environment says. There is growing concern about hidden forms of pollution, such as the fibres that rub off synthetic clothing when washed and the dust particles that vehicle tyres leave behind.

"It has been estimated that the equivalent of a garbage truck-load of plastic waste has been dumped into the ocean every 38 seconds over the past decade. Unless we do something, it is estimated that by 2050 there will be more plastic than fish in the ocean."

There it entraps and kills animals, provides rafts for invasive species to move around the world and is a vector for disease in corals. Perhaps most worrying is that much of it ends up as microplastics.

"The majority of waste plastic that enters the environment remains as waste plastic. Ocean waves, sunlight or abrasion from sand or rocks can break the plastic into smaller and smaller fragments that can then be ingested or breathed in by wildlife on land or in the sea. Humans are also consuming microplastics."

The full impact of this plastic entering the food chain is not yet known, but evidence for concern is mounting, especially as some plastics contain chemicals that are toxic at low doses, Prof Gaw says.

Because of their high surface area, microplastics are very good at binding to and concentrating chemical contaminants - at up to one million times the concentration of surrounding water.

In 2014, it was estimated that the ocean contained between 15 and 51 trillion microplastic particles. Hardly surprising when you consider that 1900 fibres can be released every time a polyester or nylon garment is washed. These tiny particles can pass straight through wastewater treatment processes.

We have arrived at this unfortunate circumstance because plastic, in its multifarious forms, is so useful.

It's lightweight, strong and cheap, and easily adapted into different colours and shapes, the Royal Society notes. The word plastic comes from the Greek "plastikos", meaning capable of being shaped or moulded. The Boeing 787 Dreamliner is 50% advanced plastic composites, which contribute to weight reductions and fuel savings. It is an important component of sterile medical products. But much of it is used to make single-use items, used once and discarded; straws and food packaging, cigarette filters and disposable cups.

As a result, the boom in global plastics production has outpaced that of almost every other material in history, Plastics in the Environment says.

A few more numbers then:

In 2015, 407 million tonnes of plastic were produced worldwide. Of that, 302 million tonnes were discarded. We're tracking towards annual production of 1124 million tonnes by 2050. In the next 15 years alone, it is expected that plastic packaging could double.

Altogether, it is estimated 8.3 billion tonnes of plastic had been produced by 2015. And it has only been produced in any real quantities since World War 2. That's more than a tonne for every person on earth. Most, about 6.3 million tonnes, has been discarded.

After half a century of furious production, the profound implications of the accumulation of petrochemical products in the environment are beginning to emerge.

Plastics in the Environment says ecological effects include changing soil structure and impacts on microbes and plant life, damage to habitats and reduction in biodiversity. A study in California found crow hatchlings were being strangled by plastic twine made into nests. Plastic mistaken for food causes starvation in birdlife and sea creatures alike.

"This threat will continue, and worsen, if the input of plastics into the environment continues to increase," the report says.

Microplastics have the potential to transfer through the food web, as smaller organisms that have ingested them, are eaten themselves.

Some of this plastic will contain toxins, carcinogens and endocrine disruptors.

"Heavy metals such as lead, cadmium and tin are used during the manufacturing process."

Additives such as persistent organic pollutants can accumulate in the tissue of animals and may also transfer through the food web.

"A rapidly growing body of research is showing that ongoing accumulation of toxins associated with plastics poses a risk to our food safety and public health," the report says.

We know it's already in our table salt, drinking water and floating on the air we breathe. A litre of bottled water contains an average of 325 microplastic particles.

This not just about a nuisance or an eyesore.

In New Zealand, the Waste Minimisation Act targets the problem with levies on waste and by funding minimisation efforts. It has been used to ban microbeads and contains provisions to encourage or require product stewardship, so those introducing waste to the system remain responsible for it through the life cycle.

However, the Royal Society report shows that initiatives to reduce plastic waste here, as elsewhere, are yet to have the desired effect.

Relying on consumer behaviour - as in the example of shoppers saying no to single-use plastic bags - is problematic, the report says, because plastic is so "embedded in all aspects of our daily life - in food production, transport, communications, hygiene, medical and personal care".

What is required is "significant change in regulation, infrastructure, technologies and social practices in order to influence household consumption".

The report looks to work under way by Prof Juliet Gerrard, the Prime Minister's chief science adviser, who is involved in a project "Rethinking Plastics in Aotearoa, New Zealand".

The obvious answer is to use less.

"The limitations on the number of times that plastic can be recycled and the difficulties of recycling products made of different types of plastics means many are calling for a radical shake up of how we design, produce, use and consider the end of life for plastics," says Dr Elspeth MacRae, chief innovation and science officer at Scion.

The approach both mitigates harm to the environment and reduces the demand for new plastic production from oil, says Dr Florian Graichen, who also works at Crown research institute Scion.

Big international companies see that there is no option but to adopt such an approach, both for business and the health of our planet, he says.

"Plastic production could represent 15% of the global carbon budget by 2050 if we don't change our approach. Plastic recycling needs to become about carbon recycling."

This sort of change is going to require regulation, say others. To date, initiatives around companies taking responsibility for their own waste have mostly been voluntary.

Meanwhile, at Wastebusters, they hope their decision will lead to people taking up the challenge to reduce plastic.

"It will be obvious to our customers that avoiding plastic containers and bottles with a 3, 4, 6 and 7 on the bottom will reduce the waste they send to landfill. We live by the waste hierarchy, so reducing waste before it's made is always better than recycling it later. Don't use it if you can avoid it."

Customers who recycle their number 1, 2 or 5 plastics with Wastebusters can be confident that nearly all their plastics will be recycled onshore by reprocessors who meet New Zealand's environmental and labour standards, Bisson says.

"Stories are circulating about plastic recycling being dumped and burned offshore, or sent back due to contamination. More of our customers are asking where their recycling is ending up, which we think is a really positive thing.

"We need more transparency in the recycling industry, and Wastebusters wants to be part of the shift to a more honest and open recycling chain. Without a functioning recycling system, the circular economy will remain just a dream."

While the pieces of that circular economy are put in place, Dr Kapitan urges us to embrace our plastic shame.

"Every choice we make, even once, to avoid plastics in our daily life ... translates to the creation of a new, plastic-free habit."

Where Wastebusters' recycling goes

Clear PET (No.1 e.g., soft drink bottles) goes to Flight Plastics in Wellington to be made into fruit containers. Includes pale green and blue tints.

Coloured PET (No.1 e.g., soft drink bottles) is baled separately, and the last load was sent to OJI Fibre, who onsell it overseas.

PET meat-trays are now baled separately so we can find a reprocessor to take them.

HDPE (No.2 e.g., milk bottles and cleaning product bottles) goes to Comspec in Christchurch to be processed into flake, which is then made into drainage pipe or other industrial plastics.

Polypropylene (No.5 e.g., ice cream and yoghurt containers) goes to Comspec in Christchurch to be processed into flake, which is then made into cable reels or other industrial plastics.

Clean, white expanded polystyrene (No.6 EPS e.g., appliance packaging). The last load went to Spain to be made into rigid polystyrene.

Clear LDPE plastic film (No.4) goes to OJI Fibre for onselling overseas.

Plastics not accepted by Wastebusters for recycling:

Plastic bottles and containers 3, 4, 6, 7

PLA (polylactic acid) vegetable-based plastic

Unidentified plastic bottles and containers (no number on the bottom)

Coloured film

Soft plastics

Tetrapak, coffee cups

Other plastics (eg toys, washing baskets)

Wastebusters does not collect or process kerbside recycling, so this new policy will not affect plastics 1-7 accepted in kerbside recycling in Central Otago or Queenstown/Wanaka.

Comments

Good to learn Flight Plastics and Comspec are utilizing recycling.

We need more efforts of this type or even turning it back into fuel.

Best you get rid of your toothbrush then ..... guess what that's made from.

Not the charcoal toothbrush. It's handle is wood.