As Guy Mollett drove away from his Redwood Valley home on the evening of February 5, he took a photo.

In it, his sizeable, modern house is bright in the slanting sunlight. It sits proudly on a landscaped section part way up a hill that six years ago was covered in gorse and grass.

But what dominates the photo is an enormous, billowing cloud of smoke rising into the blue summer sky directly behind the homestead.

It is coming from a fire just over the ridge, no more than 1.5km away, one of two wildfires that had ignited that afternoon less than 20km apart on rural land west and southwest of Nelson.

In January, many locations had experienced record or near-record temperatures. Nelson had again topped the country with 355 hours of sunshine - the sunniest month recorded in the South Island. Rainfall was well below average and soil moisture was also down. The countryside was tinder dry.

The fire in Pigeon Valley would become the country's largest in more than 70 years. More than three thousand people were evacuated from Wakefield, Pigeon Valley and Redwood Valley. A state of emergency remained in place for three weeks, as firefighters on the ground and up to 22 pilots in helicopters fought the wildfires.

On the afternoon of February 5, Mollett, a marketing manager for a Nelson orchard, had heard news of the fires and had, of course, seen the huge plume of smoke.

He realised the strong, warm wind was pushing the blaze directly towards his 2ha lifestyle property. What he did not know, until later, was how quickly it was moving. Wind-blown sparks were causing new fires up to 500m ahead of the main fire-front.

He did what he could to defend his property.

"I stayed as long as I could, damping down the peripheral boundary," Mollett recalls.

"You feel pretty hopeless with a garden hose, though."

At about 8.30pm, the call to evacuate came through. As he drove away, he did not know whether that photo would mark the last time he saw his home.

The global climate is changing, quickly.

Last week, the World Meteorological Organisation (WMO) said the physical signs and socio-economic impacts of climate change were accelerating. The WMO report said the incidence of sea level rise, sea ice and glacier melt and extreme events such as heat waves were all speeding up.

During last year, intense heat waves and wildfires in Europe, Japan and the United States alone, killed more than 1600 people and caused economic damage worth more than $NZ35billion, the WMO said.

As a result of this accelerating change, the risk of fires - such as those recently seen in Nelson and closer to home - is also increasing.

Pearce is a fire scientist with Scion, a Crown Research Institute. His forecasts come from research conducted by Scion and Niwa, the National Institute of Water and Atmospheric Research.

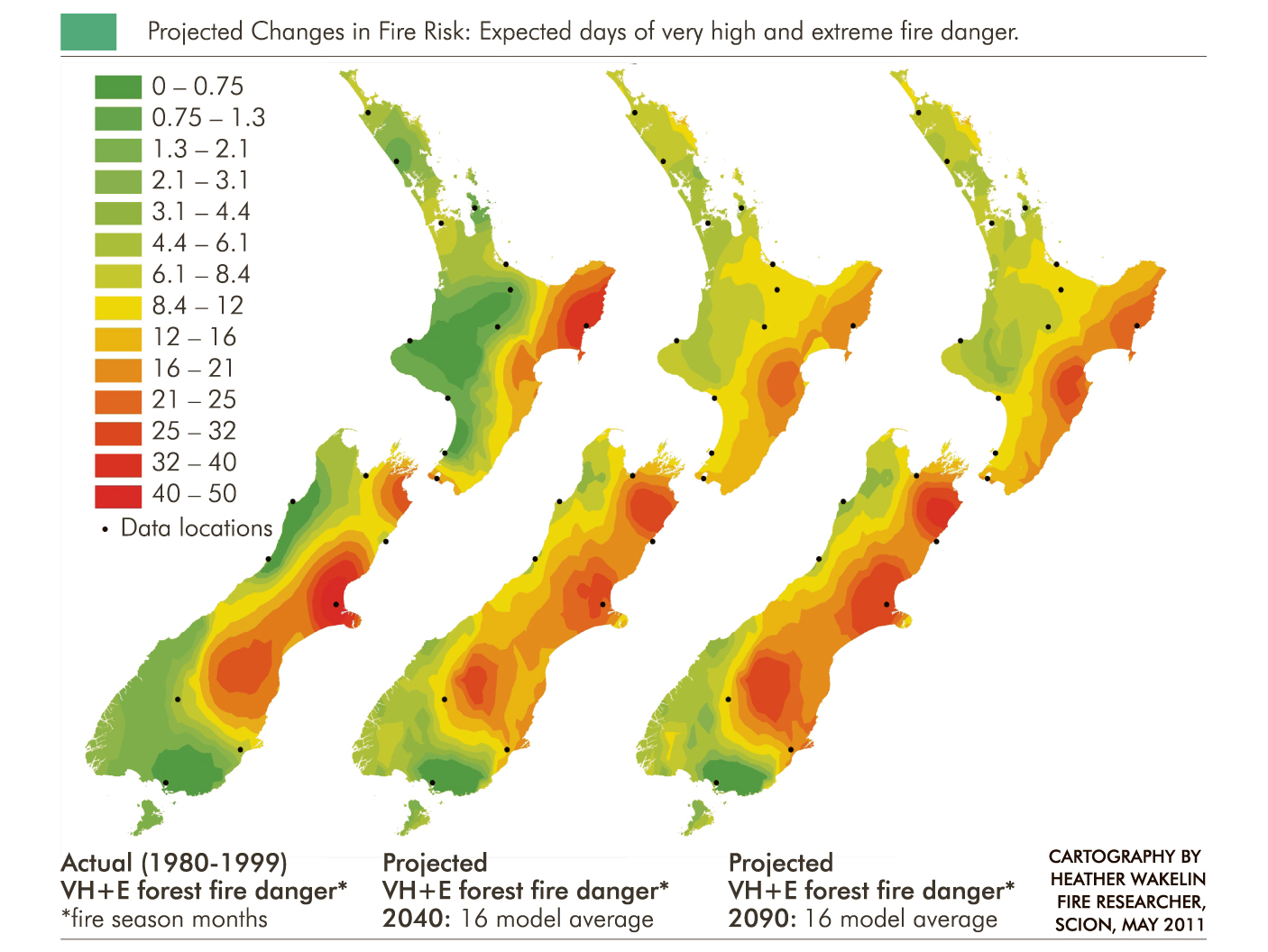

Parts of the country where the fire risk is highest, such as Marlborough, Canterbury and the East Coast of the North Island, will have five to 10 more days per year of very high and extreme forest fire danger, he says.

But even more dramatic changes - a doubling or trebling of fire danger levels - are predicted for some other parts of the country, including Wellington, Wairarapa, Nelson and coastal Otago.

Almost all of Otago is likely to experience extended periods of serious fire risk, Christchurch-based Pearce says.

Central Otago, which already has one of the most severe fire risk climates, is expected to get higher temperatures and stronger winds, pushing up its risk.

Dunedin is likely to see a bigger change. The city's risk of very high and extreme forest fire danger days could rise from an average of 5.7 days per year to 18.3 days in 2040 and 22.2 days in 2090.

Otago's principal rural fire officer knows first-hand what it is like to fight large, angry wildfires.

Still has fought them, directed the fight against them and investigated them, here and in Australia. He first started crossing the ditch to help Australians fight their large, volatile fires 17 years ago.

Still has fought them, directed the fight against them and investigated them, here and in Australia.

In 2014, he was on the front line fighting the Snowy River fire, in Victoria. During a 70-day period the fire scorched 165,806ha of bush, pasture and crops; affected three communities; destroyed nine houses; and killed 100 head of livestock.

"The fire environment changes all the time. So you have to keep your wits about you," Still says.

"Often the conditions are hot, hazardous and trying."

With large fires, you reach the point where you cannot fight them with water, Still explains.

"You're just wasting your time. Because of the fire intensity, the water evaporates before it can do anything."

Then, the tactic is to steer, and eventually control, the fire.

"You can do that by putting in bully [bulldozer] lines, burning out and taking the fuel away from the fire.

"Because the fire is so big, we can plan a day or even a week ahead. We might decide, we're going to take a stand here. And that's where you'll do that fuel reduction."

Still says we are already seeing climate-driven change to fires in New Zealand.

Last month's fire at Kokonga, between Ranfurly and Middlemarch, is a case in point.

It was started by dry lightning during a month with unusually high temperatures.

"We had four ignitions on that day, from Kokonga right through to Deep Stream.

"We get a lot of lightning, but it is usually followed by rain. Now, we are getting more of these dry hits. Last year, I had three of them in the high country in Central Otago. One of them burnt over 200 hectares."

The fire season itself has also begun shifting.

A few decades ago, the hottest temperatures, and therefore the greatest fire risk, were around Christmas and New Year.

"Now, we are still getting 30 degree days in March.

"Our fire season is starting later and running longer."

Rob Goldring agrees that fire fighting in New Zealand is having to adapt to climate change impacts.

The national adviser on fire risk management at Fire and Emergency New Zealand (Fenz) says emergency services around the world are facing the challenge of climate change. Fenz planning takes into account predictions of more high fire risk days and more extreme weather, including wildfires.

Fenz is working with the Australasian Fire and Emergency Service Authorities Council "to develop assessment tools and determine what training tools and structural requirements there are", he says.

In response to greenhouse gases causing the planet to warm up, New Zealand's Government is planning to plant one billion trees to help mitigate gas emissions.

The Parliamentary Commissioner for the Environment has acknowledged this. In his "Farms, forests and fossil fuels" report, released last month, Simon Upton says "heavy reliance on forest offsets comes with risks".

"Their increasing exposure to climate change impacts through fire, pests, pathogens and erosion further underscores their impermanence."

Otago, Canterbury and Manawatu-Whanganui are the regions likely to get most of the one billion trees.

"Significantly, the two South Island regions are predicted to become more vulnerable to extreme fire risk, further underlining the risks that a heavy reliance on forest sinks might carry," the report states.

Apart from the potential harm to life and home that raging forest fires bring, trees grown to sequester carbon could release their carbon in a flash once alight.

"The right tree in the right place" is the key to managing that risk, Pearce says.

Australian-born Dr Tim Curran, of Lincoln University, has discovered on his made-for-purpose barbecue that "we do have quite a few low-flammability [native] species". These include five finger, mahoe, ngaio, wineberry, lancewood, tree fuchsia and broadleaf.

Not all native trees are slow to burn. Rimu and kanuka are exceptions, as are native shrubs such as manuka.

"We're not saying don't plant these [more flammable] species, but if you are planting them think about what the consequences might be for fire hazard and then work out ways that you can actually mitigate that."

One solution is to plant low-flammability natives in conjunction with exotic forestry.

China leads the way in native green fire breaks - 364,000km of them are woven across the country in designs that compartmentalise flammable forestry blocks to contain fires to one section. Another 167,000km are planned by 2025.

Xinglei Cui, a PhD student of Curran's, is investigating their applicability to New Zealand conditions.

"These low-flammable trees will actually block the fire, actually stop and repel the heat and some of the fire," Curran says.

Mollet's property in Redwood Valley is indisputable proof of the value of applying that sort of thinking to private dwellings.

The fire burned fiercely through the night. The scene, after midnight, from a high vantage point was like looking into a volcano, he says.

The next day, when he was allowed to return briefly, most of the adjacent paddock had burned, except for a tennis court-sized square of grass where 10 of the neighbour's sheep had sought safety.

Another neighbour's sheep had not been so lucky. More than 50 of the 60-strong mob died in the fire or had to be euthanased.

In all, the fire destroyed three-quarters of Mollett's grazing land and a block of native bush on the property boundary.

The fire had reached the garden fence but it had left the house and out-buildings untouched.

"When we were allowed up there the next morning, there were fire hoses all over the back yard. So, there had obviously been quite a bit of activity there. And then they had just dropped and gone.

"Basically, it was still smouldering on the boundary."

What had allowed the firefighters to defend Mollett's home effectively was the landscaping choices he had made several years before that.

At a school fair not long after he had moved to the area, rural firefighters had demonstrated how fire moves up a hill.

"That made me think, we need to think about this. So, when we started landscaping, it was pretty much, keep it low around the house, nothing high flammability, choose your plants carefully and try to keep the larger trees further away."

He also thought about the lie of the land in relation to the prevailing wind.

"So, on what I thought were my higher-risk banks leading up to the property, I thought carefully about what to plant."

A property further up the same hill was extensively damaged in the fire. It had trees and shrubs closer to buildings. Everything except the main dwelling was burnt.

"Their damage was much more significant than ours. It is a bit chalk and cheese. One was reasonably easily defended, that being ours. I'm not blowing my own trumpet. It was just a bit of luck and a bit of foresight.

"The other one was more difficult to defend from everyone's perspective, just because of the planting."