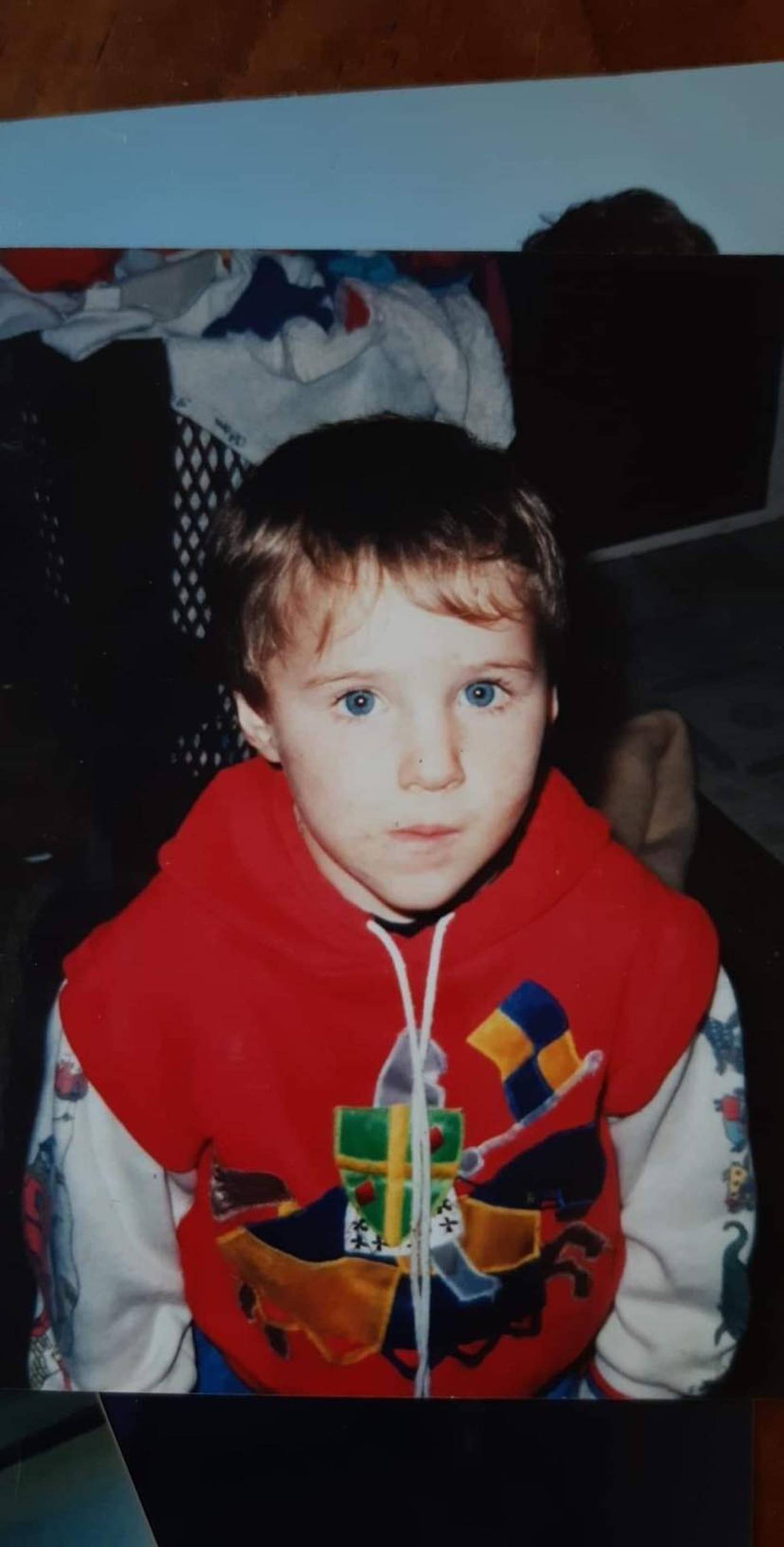

For years, Jacob Leo Skilling lived through and watched as his family suffered domestic abuse.

When he was growing up in Invercargill, his world was small and further reduced by the distance from his birth father, who had moved to Nelson.

Memories from Skilling's youth come back in fragments; the time he planned to stab a relative in the dead of night but changed his mind at the last moment. Other memories are so traumatic that the 29-year-old has buried them.

Beatings from the gangsters in his childhood home were frequent but something his warped childhood accepted as a term of endearment - it meant he was part of something.

In many ways, such as when he became a patched gang member in his late 20s, he was simply coming home to the life of violence he'd grown up with.

There were physical attacks from older men in his life. There was also sexual abuse.

Skilling's older sister, 31-year-old Courtney, also lived through the physical abuse but says her brother's suffering was more acute.

"We kind of just thought that was life. I mean, when you're younger, if you don't get things explained to you as situations happen, you just became accustomed to seeing it."

Years on, she has a good relationship with the person she says was behind some of the violence and is aware of the mental health problems that contributed to the person's actions.

"I'm really empathetic, and I think a lot of it is to do with my upbringing. When people hurt me, I don't retaliate, I try just show humbleness and love because I didn't so much get that."

He began to use the violence he'd grown up with.

"Reputation and ego start to come into it, and I didn't even realise it.

"I got to an age where I knew what I was doing was wrong, but I did it anyway, impulsively."

Doing time

Skilling always understood he would go to prison, believing the punishment was in his blood as his father and uncle had both been behind bars.

Despite viewing jail as his destiny, his first stint wasn't from a planned crime but a spur-of-the-moment group decision to rob and assault a man in the street.

Skilling left prison vowing to change - but within weeks was using drugs again. Not long after, he was charged with grievous bodily harm and sentenced to nine years in prison, serving seven from late 2008 to early 2016.

He stabbed six people in separate attacks behind bars, using whatever implements he could fashion into weapons.

"I've used a pencil, a pen, a knife, a fork a paintbrush."

It was, he says, an expression of anger that had no other outlet.

Corrections said its records showed Skilling was involved in four fights with other prisoners "and on several occasions, he was suspected of assaulting other prisoners".

During this period in jail, Skilling found out he was going to be a father. The woman visited a few times "but we just stopped because it's not a good place".

She later moved to Australia.

Skilling was released on parole to Odyssey House, a residential rehabilitation centre in Christchurch.

He admits he continued to make mistakes - but credits his time at Odyssey House for planting the seed for his future on the right side of the law.

During his stay, he met Anna Christoforo, who then was the operational manager at Odyssey.

She says Skilling was always enthusiastic and made a full commitment to recovery the day he walked through the door.

It's not an easy road, and although the programme is challenging, Christoforo says it's only the beginning and the real work happens after clients leave.

Leaving the programme can be daunting; those who leave face a world where housing and employment difficulties are even more pronounced than usual, as many have criminal convictions.

And staying on the straight and narrow in the "real world" was not simple as Skilling thought.

The down

Skilling moved from Odyssey into a reintegration house. He was working and playing league - his nickname was "the flash" because he was so fast.

But then he met a former associate in the gang scene and fell into old habits and began formalising his gang connections.

Becoming a patched member wasn't about family or brotherhood for Skilling - it was about money and reputation.

Despite that allure, he left the gang, but a year later his life was upended again when he was seriously assaulted and left in a coma.

It was, finally, the push Skilling needed to make real change.

This journey from childhood abuse into the gang scene is incredibly well-trodden, says University of Canterbury director of criminal justice Dr Jarrod Gilbert.

He told the Herald that once people were in the gang, they became isolated because the gang became their family and their friends.

"It's often all of your life and so it's incredibly difficult to leave and in fact, this is why you often see the church involved. People go into the church, because they are substituting one family for another."

"Freedom," is how Skilling describes finding the church and living without crime.

His induction into the faith came from the Passionate Sons Ministry, of which he is now a member.

When he stepped into a church, the Living waters Christian centre in Halswell, after walking away from the gang "I just felt it, the presence, the Holy Spirit".

"You feel convicted, you've got to repent, you've got to deal with it and apologise, even if people aren't willing to accept your apology, that's all you can do."

By turning his back on crime and the gang, Skilling says he was shunned and labelled a traitor.

But he takes comfort in his belief that God has a plan.

After discovering "the light", he says he wanted to share it to help pull others away from the world he had escaped.

Skilling says his torrid upbringing has given him a wealth of experiences to help others make a change.

He founded the Broken Movement Trust in 2019 and it was formally registered as a charity in March last year.

Skilling and others he works with try to help young adults, their whānau and their communities.

Those running the organisation aren't outsiders, according to Skilling. He says they have been there and they know what it's like to struggle.

They host community events, help mentor those who are struggling and even provide food and shelter for homeless people.

Now, from the other side of the bars, he wants those stuck in the cycle of violence and crime to join him.

"Don't live in the fear. Be brave and step out in the shadows because the longer you live in the shadows, the harder it will be to escape it."

Skilling is now studying mental health and wellbeing at Open Polytechnic. He describes it as coming full circle - he's spoken at prisons where he'd previously been an inmate.

"I'm free from anxiety, I'm free from depression and I actually feel comfortable in my skin now."

His sister, Courtney, says she's proud, given everything Skilling has had to overcome.

"He's come such a long way."