Instead, the virus appeared to have been passed through aerosol particles suspended in the air - within just 50 seconds - during routine swabbing in Christchurch's Crowne Plaza Hotel last September.

A virologist involved in the investigation said the curious case raised questions about other instances where surfaces have been blamed for transmission - including the purportedly-contaminated lift button at Auckland's Rydges Hotel.

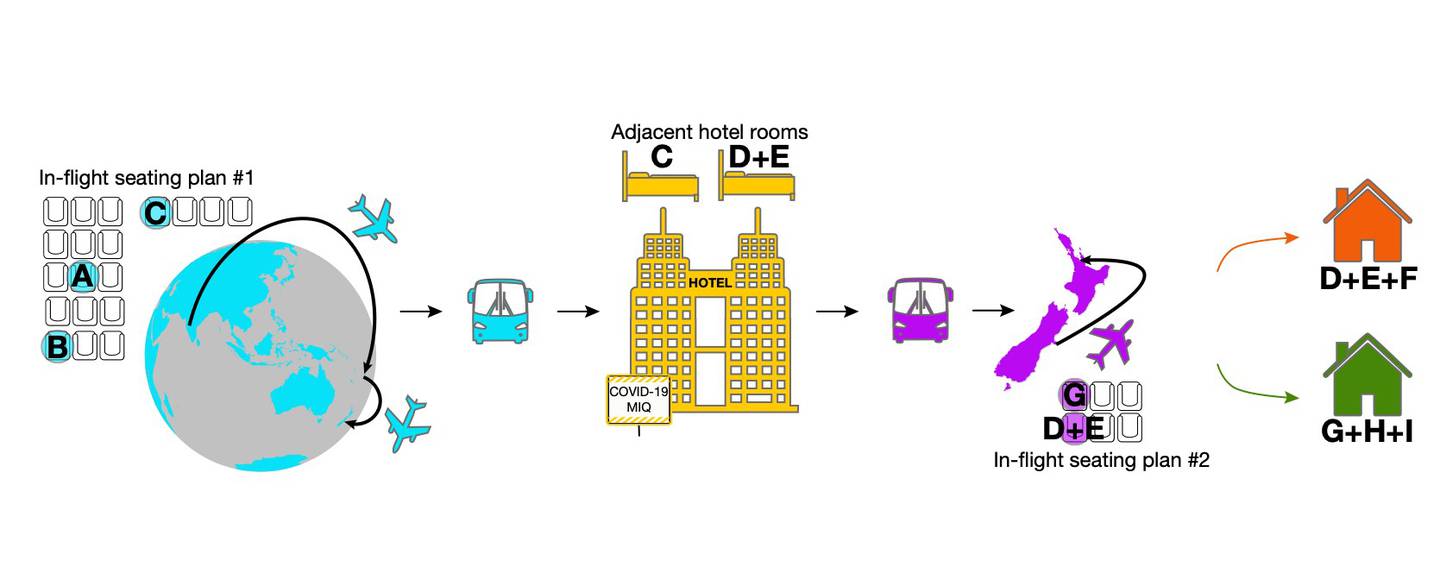

The inquiry, set out in a just-published study, pieced together a complex chain of transmission that resulted in six community cases.

Unravelling the chain

The chain first came to light on September 19, when a fresh community case was reported in Auckland.

That person - a recent arrival from India, and denoted as "case G" - had earlier tested negative on days 3 and 12 during their stay at the Crowne Plaza.

At the time, director of public health Dr Caroline McElnay said the person was likely infected on a domestic charter flight by a person seated behind them, who'd also just completed MIQ.

As for how that person was infected, McElnay suggested the intriguing possibility of touching a shared rubbish bin at the MIQ, which may have been contaminated by another infected guest.

That theory now appeared unlikely.

Nearly a month earlier, on August 27, case G was part of a cohort of 149 repatriated travellers who'd returned from Delhi, via Nadi, Fiji.

Among those who arrived in Christchurch, eight later tested positive while in MIQ.

Of those eight, three were shown to be genomically linked, and were denoted in the investigation as cases A, B, and C.

During the first 18-hour trip from New Delhi to Nadi, these three travellers sat within two rows of each other - and it was possible that cases A and B might've been infected during or before the flight, from a common source.

On arrival in Christchurch, passengers were disembarked in groups of 10 to enable physical distancing to be maintained in the terminal, and each case was provided with a fresh surgical mask.

The cohort was transferred by bus to the hotel, where each room had its own bathroom and no balconies.

When case C tested positive on day 12, the patient was moved to the isolation section of the facility.

Before their relocation, an adult and infant child, who had returned from India on the same flight, were in the adjacent room.

These two people - denoted as cases D and E - later tested positive while in Auckland, having earlier returned negative tests during quarantine.

Yet a CCTV review showed there was no instances where cases C, D or E were outside their rooms at the same time.

So how was the virus passed?

The investigators found the likely answer when assessing footage of routine testing that took place in the hotel hallway on day 12.

"They would open one person's door, test them while literally standing in the door, and then close the door," said study co-author ESR and Otago University virologist Dr Jemma Geoghegan.

It so happened that there was a 50-second window between closing the door to the room of case C - and opening the door to the room of cases D and E.

A commissioned review of the ventilation system found that the rooms in question had a net positive pressure compared with the corridor, which further made the facility's communal bins a less-likely culprit.

After completing MIQ, a now-recovered case A, along with cases D, E and G boarded the 85-minute chartered flight to Auckland.

All passengers were required to wear masks, and the flight was at around 50 per cent occupancy.

Case G sat directly in front of case-patients D and E, and was likely infected at that point, while case A sat at a distance.

On arrival at Auckland airport, cases D and E were met by a household contact - who became case F - and case G was met by household contacts, who became cases H and I.

Solving the mystery

Of the nine cases, Geoghegan said genome sequencing and epidemiological investigation established who likely infected who.

But it initially left puzzling questions as to how some of those cases were infected with the virus.

"When we looked at that transmission chain, the biggest question was, how did case C infect cases D or E."

The sequencing results enabled a team at Canterbury District Health Board to investigate and identify how transmission of the virus was able to happen in managed isolation without person-to-person contact.

"Once this was established, then the rest of the transmission pattern could be explained through in-flight and household transmission," Geoghegan said.

The investigators then drew on CCTV observations within MIQ, inflight seating plans, and epidemiological data.

Instead, the evidence pointed to the virus being passed on later, within MIQ.

Canterbury DHB lead investigator and study co-author Dr Josh Freeman said while initial indications suggested the rubbish bin was involved, aerosols were later ruled the likelier explanation.

During swabbing, masks have to be lowered briefly to expose the nose - and this was thought to have increased the risk of cases D and E being exposed to infectious aerosols that would've been hanging in the air.

"These findings provided just one part of the puzzle, but investigations like this can assist scientists in New Zealand and around the world as we seek to better understand Covid-19 transmission," Geoghegan said.

"It's good to learn new things - and this has changed the way that people are tested in Christchurch. They're not tested in sequential order in their rooms anymore."

No changes were suggested for domestic travel, given that all passengers were deemed to be negative for the virus, and regardless, were required to wear masks.

Geoghegan said the findings were relevant to other MIQ cases, such as a spate of infections that forced the emptying of Auckland's Pullman Hotel.

An investigation also found that droplets in the air, not contaminated surfaces, were likely to blame.

Another case was the passing of the virus from one person in Auckland's Rydges Hotel to another, who entered a lift minutes apart.

It's been widely suggested the link was a contaminated button in the elevator - but such cases of spread by surfaces remain extremely rare.

"This study points to the fact aerosols are usually the more likely source in unventilated spaces," Geoghegan said.

"Hotels aren't purpose-built facilities - they're repurposed - and they may be providing opportunities for these things to happen.

"As always, the best way to protect yourself and others against Covid-19 is to continue with basic public hygiene measures, use the NZ Covid Tracer App to record your movements, stay home if you're unwell and ring Healthline if you think you need a test."

The study was also co-authored by McElnay, Tara Swadi and Tom Devine of the Ministry of Health; Dr Nick Eichler and Dr Felicity Williamson of Auckland District Health Board; Dr Craig Thornley of Hutt Valley District Health Board; Dr Jillian Sherwood, Matt Storey, Dr Joep de Ligt and Dr Una Ren of ESR; and Dr Cheryl Brunton and Dr Sarah Berger of Canterbury District Health Board.

It was funded by the Ministry of Health, Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment's Covid-19 Innovation Acceleration Fund and ESR's Strategic Innovation Fund.