The Pilkington governance review expressed frustration that the rugby community, though aware of a rapidly changing world, still struggles to modernise and adjust.

Despite a "clear problem definition" and multiple reviews, "big decisions needed in the interests of the game" continue to be avoided.

It’s worth noting, however, that the report did not offer an explanation for why change has been so hard. It may well be "one of the most conservative of this country’s major sports", but why is this the case?

Furthermore, could it be that the recent decision by some provincial unions to reject the expert panel’s key recommendation – that New Zealand Rugby board directors be entirely independent – is evidence the real problem goes undiagnosed?

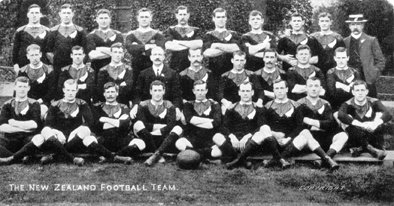

So, what is it that makes the All Blacks the All Blacks? Pilkington raised the matter of the nation’s colonial past.

"New Zealand had always – has always – had a certain insecurity about its place in the world," observed historian Jock Phillips.

"We’ve always got a certain anxiety that we are falling off the edge, that we don’t really count. The [1905] tour gave New Zealanders a sense that they had a role to play in the empire."

Though helpful in clarifying why rugby is synonymous with the national identity, it doesn’t really get into the how.

I took some time to reflect, casting my mind back to decades of Bledisloe Cup disappointment, living across the Ditch. What struck me most about the All Blacks – from watching them play during the 80s and 90s and learning about legends such as Colin Meads – was their Zen spirituality, aka amateurism.

The team honoured its opponent and the game, based on a moral code independent of the official rules.

They always looked utterly composed, as if nothing literally mattered. The players exhibited a calm attentiveness, their actions guided not by the need to win, but by a connection that put heart before head, that was more art than science.

Something did matter, obviously, but it was only found in the flow of the physical contest, too immediate for the mind to understand, quantify or control.

According to the Pilkington review, "the world that produced the original All Black story no longer exists".

I think this is both revealing and wrong.

There’s a material aspect to life that is constantly changing. Thanks to the wonders of science and technology, this is often for the better.

But there is also something higher, a part of life that is characterised by the absence of change. What is morally and aesthetically meaningful today is just as applicable as it was in 1905, and still will be for anyone around 100 years from now.

The professional era sought to enhance the material side of rugby.

Change was presented as a no-brainer. Why not use the science of sport and high performance? How could anyone have a problem with securing the future of the amateur game by cascading money from the top down to clubs, their players and volunteers?

Yes, it would bring greater complexity, but this could be managed through a hierarchy of governance that ensured, as noted by Pilkington, that provincial unions are "trusted to know their patch and how best to run their business within it – but not in an isolated way".

There was one major risk with this strategy.

In order to break down any parochialism and build an integrated global structure, NZR had to foster a rival, head-before-heart culture.

It was necessary to create the impression that what really matters, on and off the field, can be understood and measured for the purposes of improving the game.

As often seen in politics and business, the larger and more complicated the process of bringing it all together, the greater the chance those in the upper echelon lose touch with reality as a whole.

Caught up in the contest rather than the spiritual opportunity it affords to do the right thing, they discount that facet of life that has nothing to do with money, power or the abilities of a board.

Could this be why provincial unions have been difficult? Perhaps they sense that endless change for the sake of change now threatens to ruin, not complement, the flow of the game, the very thing that has provided historic meaning for so many New Zealanders.

Like a new priestly class, modern administrators seem bent on control. Reliance on an unwritten moral code isn’t an option. There’s too much at stake to trust in some give-and-take on the field. The default is more subjective whistleblowing and more sanctions, meted out by moralisers who sit in replay booths above the fray, reducing a noble game to a series of hair-splitting technicalities.

It is possible, of course, to achieve the best of both worlds, where professional-material and amateur-Zen cultures work in harmony.

It just means being open and honest about what changes and what doesn’t – and which is the most important. If bodies like NZR and World Rugby want real unity, they need to acknowledge that, while it can be made safer and more inclusive, the heart of the game is always beyond any conscious improvement.

And this includes good governance.

— Mark Christensen is a Wellington writer.