The big policy announcement in that speech was a NZ First proposal for an overhaul of KiwiSaver.

Should Mr Peters be in a position to enact it after next year’s election, his party seeks not only that KiwiSaver become compulsory, but that mandatory employee and employer contributions be increased — initially to 8%, ultimately to 10%.

Compulsory retirement savings of some sort is a long-standing NZ First policy, one born not only by the preponderance of seniors in the ranks of party membership but also by its realisation that as the population ages that the current universal national superannuation scheme — which NZ First supports — comes ever closer to becoming unaffordable.

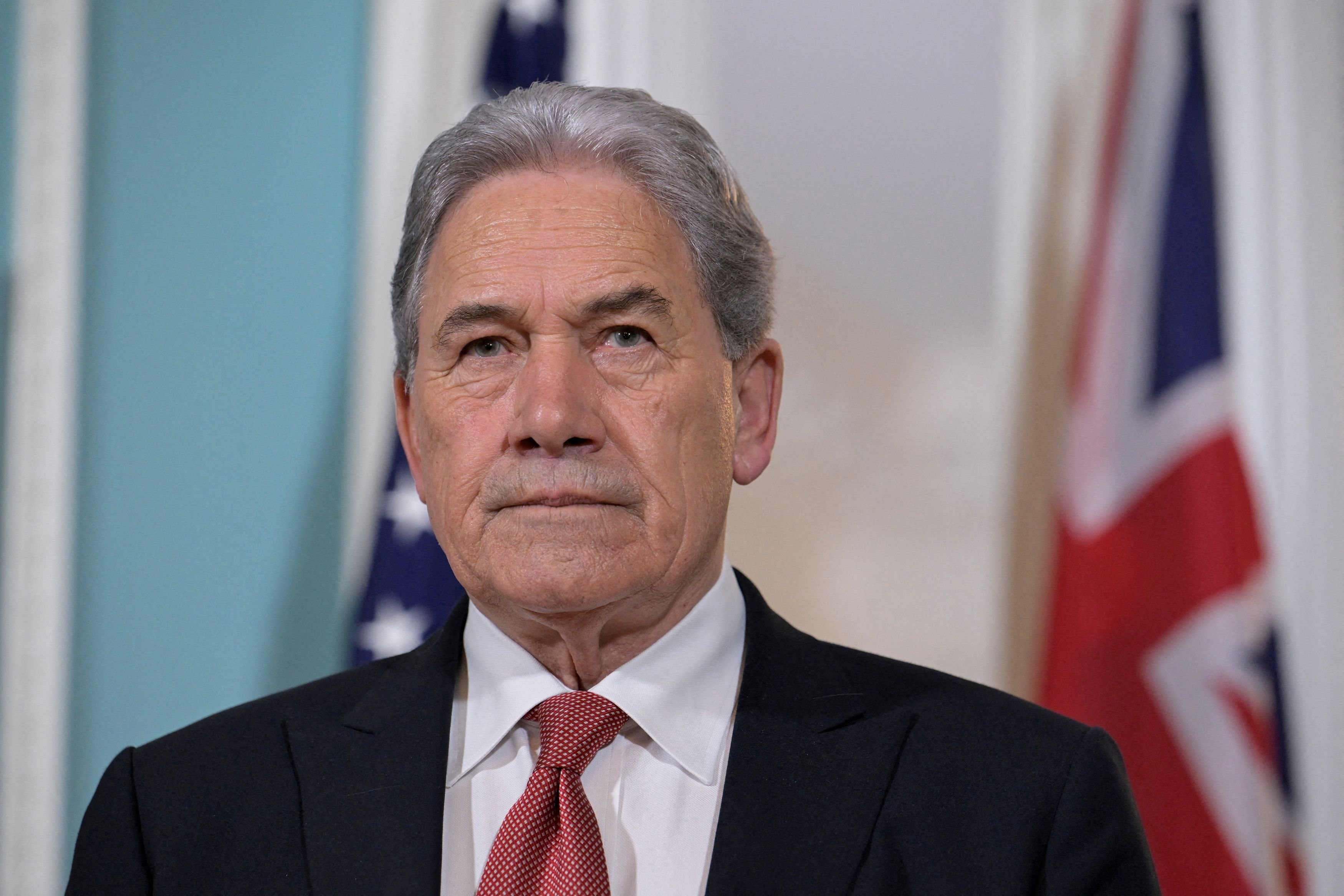

NZ First was in coalition with Labour when KiwiSaver was introduced, so Mr Peters has a long-term connection to the scheme. It is no surprise that, even though he has criticised its operation in the past, that in general he wants a government-backed savings scheme to succeed.

That fund would be expected to be a key partner of the already NZ First-created regional infrastructure fund, which demonstrates some level of joined up thinking as to how such a scheme would work and generate income of its own.

Less well developed, seemingly, is how NZ First would fund the changes to KiwiSaver contribution rates. Mr Peters said it would be by both employers and employees receiving tax cuts to cover the increases — the presumption likely being that the cuts and the contributions would offset each other and hence have a neutral financial effect.

Mr Peters’ defence that the policy was not being introduced at this point, only the principles of it, somewhat undermined his case, but he was right to point out that compulsory savings schemes do exist overseas — e.g. Australia.

Getting the support of party faithful in Palmerston North is one thing, but getting it past his current coalition partners should the present governing arrangement survive the 2026 election is quite another.

Act New Zealand released an alternative budget last year which preserved government subsidisation of the scheme but with income testing attached. While Act has never met a tax cut it didn’t like, it may find tax cuts for a mandated savings scheme a difficult trade-off to make given its insistence that people be allowed to make their own decisions about their own money.

In 2023 National campaigned on giving savers more choices for how to use, or with whom to invest, their KiwiSaver contributions. Its plans to make superannuation affordable centre on raising the eligibility age — something which Mr Peters will not have a bar of.

All three parties, in this year’s Budget, did sign off on a gradual contributions increase up to 4% for both employees and 4% for employers. That, however, was balanced by a decrease in the government contribution.

The Retirement Commissioner said even a small change was a good change, her study of the changes suggesting that they could result in retirement funds lasting on average approximately 30% longer for a median earner who contributed to KiwiSaver for 40 years.

However, research commissioned by her office suggests that in 2050 (assuming policy settings do not change) government spending on NZ Super will be about a fifth higher that it is now. Add in longer life expectancy and an associated higher amount needing to be spent on health, and the report suggests that rising taxes, reduced public services, or growing debt might be needed to fund it.

On the plus side, the first wave of retirees who will have had KiwiSaver their whole working life will be on the cusp of their golden years — good savers may enjoy a comfortable rest of their lives economically, but NZ Super was still expected to be an important part of income for most seniors.

Mr Peters may not have any or all of the answers, but at least he is asking the right questions before it is too late for them to be considered.