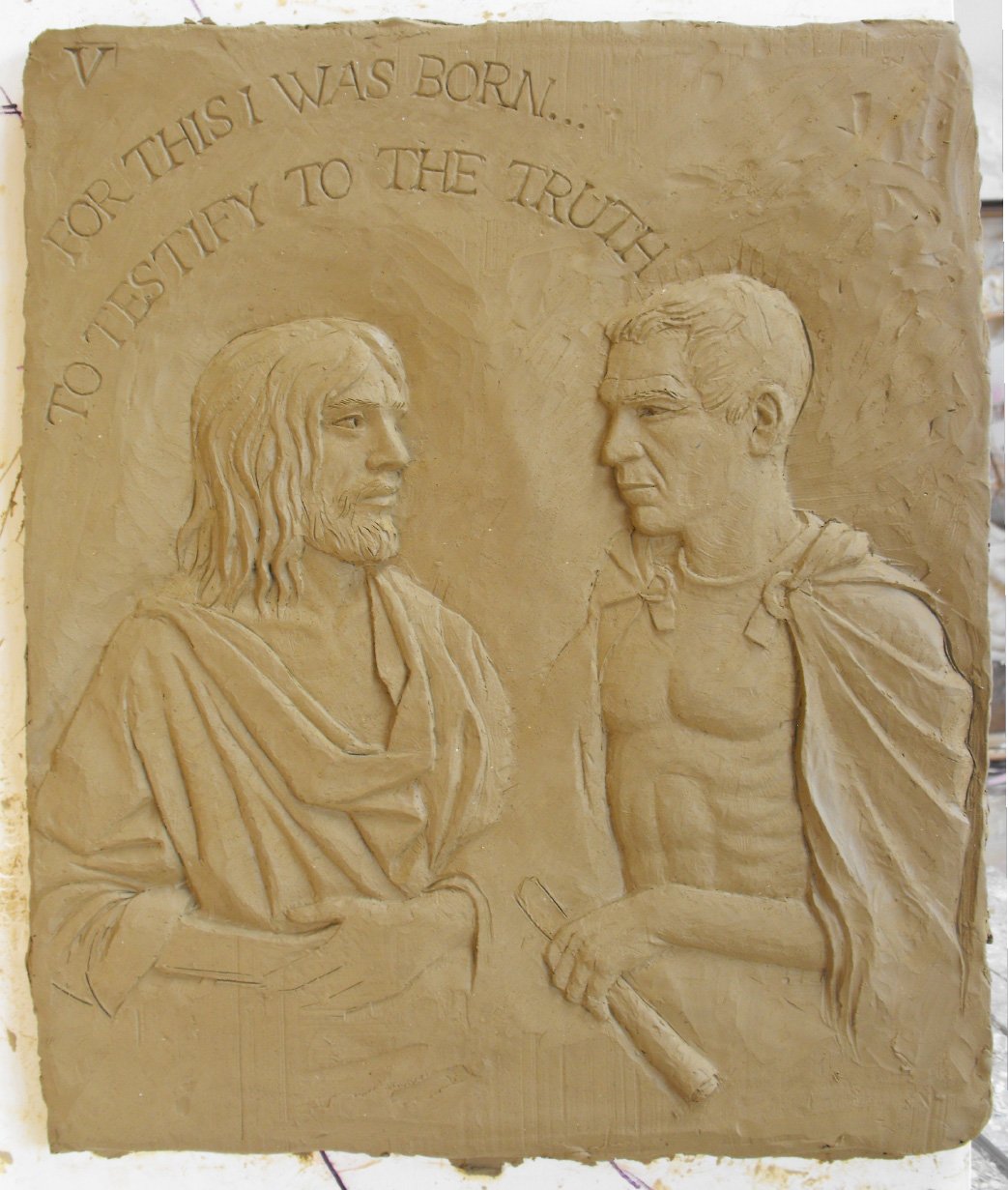

Pilate was a shrewd political operator, though one with a conscience. Pilate asks Jesus directly if he is a king. Jesus answers in the affirmative. "You say that I am a king. For this I was born, and for this I came into the world, to testify to the truth."

Truth involves listening, but to whom? The shocking and astonishing thing is that Jesus equates himself with the truth; his own voice is the truth. Jesus says to Pilate, the political leader who has the ability to save or end his life: "Everyone who belongs to the truth listens to my voice".

Truth requires us to listen. In order to listen well, we have to want to listen. Pilate, however, decides that he does not want to listen. Pilate is deeply unsettled by Jesus. And the more Pilate listens to Jesus, the more uncomfortable and afraid he becomes. He seeks to sidestep this discomfort.

In response to Jesus’ declaration that he is the "truth", Pilate states sarcastically: "what is truth?". And then, like any shrewd politician, he turns to the crowd, seeking their opinion and ultimately follows their wishes.

Pilate sentences Jesus to death by crucifixion on a cross — a first-century instrument of Roman imperial torture. Face to face with "truth", Pilate refuses to listen. His actions are illustrative of one who neither knows nor belongs to the truth.

Two thousand years later on Good Friday, Christians all over the world remember Jesus’ death. For Christians, truth is revealed to us in Jesus Christ. On the first Good Friday, truth gets pushed out of the world on to a cross.

Humanity finally has things on its own terms. Good Friday is deemed "good" because it unmasks our deep and distorted desire to live in a world without truth.

In a world without truth, humanity has no-one to listen to but ourselves. We become our own "truth". This leaves us in an awful place. Conditioned to see ourselves as the centre of the world, we are our own kings and queens, living our lives according to our own standards, regardless of the cost to our neighbour near or far away.

The gift of Easter is that of posing again this ancient question of "what is truth?". On Easter Sunday, as they have for 2000 years, Christians will celebrate the answer to this question.

The truth, they declare, is a living person, raised from the dead, Jesus Christ.

The great feast of Easter is a perennial thorn in the flesh of humanity’s desire to be its own master and ruler. Easter disrupts our efforts to establish a world that functions purely on our terms, however ghastly.

This is good news, although profoundly subversive of our age-old attempts to place ourselves as the centre of all things. The odd and unsettling news of Easter is, in the end, wonderful news. There is truth. To listen to the truth is to listen to Jesus.

Pilate, like figures past and present, may succeed in pushing the truth out of the world for a time, sometimes even with the blessing of religious authorities.

The wonderful reality of Easter confronts the futility of such actions.

"I have seen the Lord," says Mary Magdalene on the first Easter Sunday morning. Truth lives and speaks forever.

"Everyone who belongs to the truth listens to my voice."

- Christopher Holmes is an ordained minister and professor of theology in the University of Otago theology programme.