Some Stewart Islanders think they can wipe out all predators from their piece of paradise, allowing endangered native species to thrive. A ‘secondary kill’ 1080 poison strategy to kill feral cats is a controversial part of the plan.

Daniel Cocker waits with a backpack on the banks of remote Freshwater River in Stewart Island. We’re the first people he’s seen for days and he has a surprise for us.

The boat has barely pulled in to take him back to Oban, where a hot shower and his own bed await, when he yells that he has one, and to come to the hut to see it.

He places a small female tabby cat on the grass. It’s very much dead, but lying there, with its head tucked close to its front paws, you can almost tell yourself that it’s semi-curled into a sleep position dreaming of successful hunts.

It’s bedraggled and thin and as Cocker points out her sad eyes it’s hard to not to feel a bit sorry for the cat.

But he has no regrets and says he was happy to trap it. “There’s definitely still a few more out there,” Cocker says.

The fresh-faced 24-year-old, is also known as Dotterel Dan. He’s one of the Department of Conservation (DOC) rangers dedicated to saving the Southern New Zealand dotterel / pukunui from extinction.

Feral cats are the birds’ number one enemy and in recent years the rangers have been fighting a losing battle against the feline predators. Scores of birds have been lost to them, including the dotterel bearing his girlfriend’s name.

Today’s cat catch is another notch in the tally of the 20 to 30 cats they've caught at just one of the birds’ breeding sites on the island.

“They just reinvade so quickly,” Cocker says, a little forlornly.

Helping keep the dotterel alive means days alone spent in the field trapping cats. This is no easy feat. North Island dotterel nest on beaches, but their southern relatives opt for inhospitable mountain tops, some well-known for having howling winds so strong it’s difficult to stand.

Despite the huge effort, trapping alone barely stems the tide of cats. Hungry rats steal the bait from the cat traps before cats come across it and the wary felines are naturally suspicious of traps.

Back at DOC's Stewart Island office in Oban another ranger, with the pelt of a cat draped casually over the back of his office chair, shares a spreadsheet. It contains information about every cat they've trapped at each dotterel breeding site, stretching back to November 2022. The data gives the battle perspective. Including the cat caught that day, the tally sits at 122.

The cats which have been caught outnumber the 105 dotterel left.

Cocker knows each of the 105 remaining birds by sight. These dotterel are the world’s rarest wading bird, a fact he shares with equal parts pride and sadness.

Last year was a good breeding season where numbers increased from 101 to 105, but the seasons before were a different story.

“When your population's dropping, when you're seeing 40 to 50 adults dying each breeding season, that's the stuff that keeps you up at night,” Cocker says.

There’s a goal to build the population to 300 by 2035, but while cats prowl nest sites, it feels like a pipe dream. With 40 birds killed by cats each year, extinction seems more likely than the 10-year hope of tripling the population.

With the birds poised on the edge of oblivion, drastic action has come in the form of small green cereal pellets laced with sodium fluoroacetate, a controversial poison more commonly known as 1080.

It’s a bold move, which almost feels like a hail mary. It’s pinned on the hope an unfortunate chain of events will unfold for the cats.

The hope is that rats will eat the 1080 pellets, and that cats will eat the poisoned rats and die themselves, giving the dotterel a clear run at a successful breeding season.

An army of Trojan rats

There’s more than one way to kill a feral cat. Traps are commonly used, but require checking to dispatch cats if they’re in a live capture trap, and rebaiting. This means hours in remote areas, often traversing rough terrain and dealing with bad weather. When you’re trying to reduce cat numbers in huge areas of rugged land, the human-power required to consistently trap can be an ineffective strategy.

The hope is to return the island to something close to what it was before predators were introduced; there’s even talk of the return of kākāpō, which were evacuated from the island due to cat predation.

The programme is led by the non-profit group Zero Invasive Predators (ZIP), with DOC alongside. ZIP, an organisation set up by DOC and philanthropists the Next Foundation, has already been working on large-scale eradication projects on the mainland. If Predator Free Rakiura is successful it would be the largest eradication project completed on an inhabited island.

In order to get there, 1080 could be used on other parts of the island, but with the dotterel desperately needing a breeding season without cats picking off birds and their chicks, it was decided to shift the operation to include key nesting areas and combine forces with DOC, in a massive effort to supress and eradicate cats.

It’s a contentious plan for a small island community, with an area of 43,000 hectares targeted with a poison that has plenty of critics.

A small community divided

Stewart Island / Rakiura is approximately 180,000 hectares, has a population of 400 people and roughly 27 kilometres of road. In the off season the only place in its sole town of Oban to buy a cooked meal is the South Seas Hotel, which serves as accommodation, cafe and bar. It’s the type of place where you lift a couple of fingers from the steering wheel in a friendly greeting to everyone you pass.

It has a small island charm, with plenty of quirks and personalities. There’s shelter alongside the pub, commonly known as the bus stop, although there is no bus service on Stewart Island. Inside is a bench, cushions and couches. An official looking sign at the front of the stop lists numbers related to Oban: Established 1870, Elevation 0, Population 300, Postcode 9818, Average rainfall 1489. Inexplicably, these numbers are then totalled.

Parked beside the bus stop is a ute with a yellow sign perched on it urging people to say no to “poisoning our paradise”. It’s just one of numerous yellow signs dotted throughout the community sharing the same message.

The ute belongs to Gordon Leask, commonly known as “Fluff”, who can often be found at the bus stop. Generations of his family have lived on Stewart Island, there’s even a Leask Bay in Oban. Leask runs a boat charter company with a boat originally built in 1907 by his father’s great uncles. He takes people out fishing, bird watching, and drops deer hunters to places Stewart Island’s 27 kilometres of roading don’t reach.

“It’s as big of a split as we had over Covid and everyone was sort of just getting over that,” he says.

Ask him if he’s lost friends and with an uncomfortable chuckle he describes things as “very awkward”.

The way the 1080 operation is being handled leaves a sour taste for Leask. He feels like there is no consultation and it’s discussed as a done deal, whether the locals support it or not.

The Protect Rakiura Trust, a charitable organisation set up in response to the operation, opposes what it describes as harmful pest and predator management efforts. Its website and a Facebook page urges people to get involved. Leask is one of the trustees.

Funds have been raised, meetings held and $10,000 worth of the yellow signs and bumper stickers printed and displayed throughout the community.

Relationships have been strained. As one local explains, people declined to do a show of hands of who was in favour or against 1080 at one meeting, but the signs outside houses and plastered on vehicle bumpers do the job anyway. In this tiny community, the locals know where each other stands on the topic.

Tension over the 1080 operation built and members of the trust were called to a police meeting and reminded about what’s considered lawful protest. The Protect Rakiura Trust’s chairperson, Furhana Ahmad, told the Southland Times some members were concerned they were under surveillance. She felt a protest sign placed on land neighbouring a helipad and what she described as a petty accusation of a group member shoulder-barging someone in a narrow aisle of the supermarket were to blame for the police involvement.

Ahmad’s a slight figure, often seen walking briskly to and from the ferry terminal, with brochures for the nature tours her company runs in hand to pass out to tourists. Her tour shop sits across the road from the Department of Conservation office and she’s one of the island’s most outspoken critics of 1080.

She's not convinced feral cats are the main cause of the dotterel’s dwindling population. She has a list of reasons for their plight and most point the finger across the road, at the Department of Conservation.

DOC sprays marram grass with weedkiller, which she says poisons the invertebrates the birds feed on. She also says there’s a lack of experience in the team due to staff turnover, the rangers are disturbing birds during breeding season by getting too close to them. Likewise, she feels cameras pointed at nests disturb birds. Finally, she thinks tracks used by DOC to get to the mountain tops where the birds nest are acting as highways for cats, leading them straight to the nests.

DOC operations manager Jennifer Ross doesn’t agree with Ahmad’s view.

The marram grass is only sprayed in one area where birds feed. In 20 years, no link between the spraying and bird health has been observed.

She says the dotterel rangers follow best practice and are trained to minimise disruption to the birds, especially during sensitive periods. Cameras haven’t been routinely trained on nests since 2021 and research has shown feral cats find the nests, whether there are tracks or not. If the cats do use the tracks, she points out they will encounter multiple baited traps. Staff turnover happens in any workplace, but Ross says there have been efforts to make sure knowledge is passed on.

When it comes to Stewart Island being in balance Ross has a list herself; of species which have gone extinct due to introduced predators. Bush wren, South Island kōkako and Stewart Island snipe are all gone. Kākāpō were evacuated from the island because of feral cats. Pukunui, Stewart Island robin and fernbird numbers have all declined dramatically. Ross describes Stewart Island as a fragile ecosystem where native species are struggling against pressure from pests.

For DOC, feral cats are the biggest pest to tackle to give pukunui a shot at a future and 1080 could be the tool to do that.

The poison has been used in New Zealand for pest control since the 1950s, but there’s always been opposition to it. In 2011, the Parliamentary Commissioner for the Environment conducted an independent review into its use, looking at effectiveness, safety and humaneness. It suggested the use of the poison should continue and even increase, but resistance to its use continues.

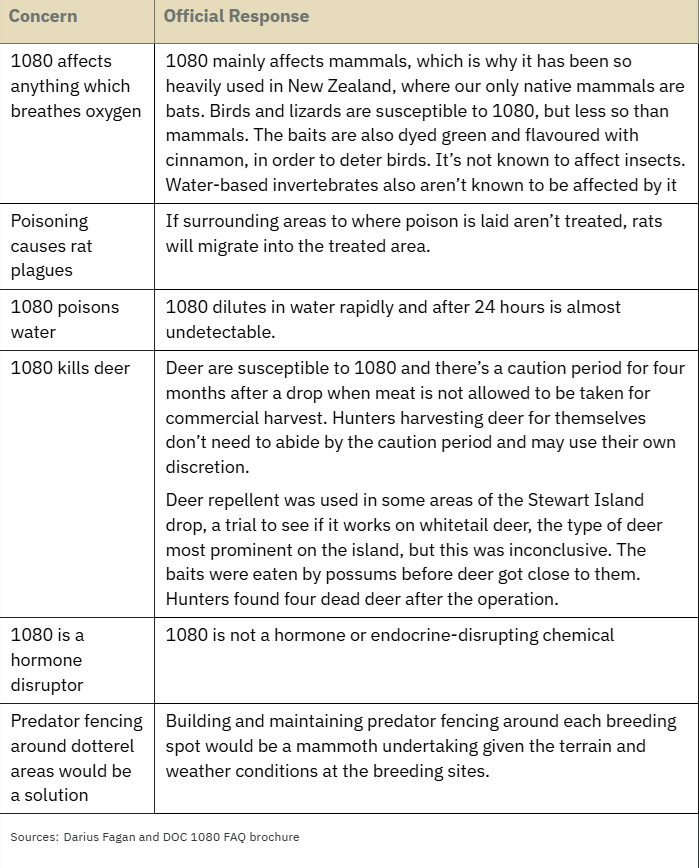

Many of the Stewart Islanders’ concerns echo well-trodden territory raised in previous debates surrounding Aotearoa’s use of the poison.

Leask says previous poisoning efforts on the island have resulted in rat plagues. He points out that more rats means more food for cats and this could mean a higher kitten survival rate. He’s also concerned about the effect of the poison on birds, saying it’s a hormone disruptor.

“Do you really want to swim in the sea where 1080 is discharging into the waterway?”

She distrusts sampling work conducted after the drops and believes the questions she asks aren’t answered properly.

Greg North is another local who’s against the use of the 1080. He came to Stewart Island on holiday in 1988, with a pack and rifle and has never left.

As far as he’s concerned the jury is still out on how effective the repellent is for whitetail deer, which are the predominant species on the island. One trial attempting to establish this failed as the baits were eaten by other species before deer encountered them. North worries that if the repellent doesn’t work, a large percentage of whitetail deer could die.

He questions whether surrounding the areas where dotterel nest with predator fencing to keep the cats at bay might be a better solution than relying on 1080.

His biggest concern is that in chasing the dream of eradicating predators, Stewart Island could get locked into a neverending cycle of 1080 use.

He thinks the island is too big to get a 1080 drop in one go, so blocks will need to be targeted sequentially. “They will kill most of the rats, but I believe they’ll never kill the last rat here. There will be reinvasions,” he says.

Despite the opposition and protest signs, the 1080 drop went ahead in August. More than 100 tonnes of poisoned bait was dropped by a fleet of helicopters over a large area, including most of the mountain tops dotterel nest on.

“They're experimenting with Stewart Island's economy and Stewart Island’s way of life,” he says.

The aftermath

For dotterel ranger Cocker the effect of 1080 was immediate in the breeding sites where it was dropped.

“We were catching nothing in our traps, which is the first time ever in three years that we’re actually catching nothing and getting no bait taken.”

Hard data backs up his observations. Hundreds of trail cameras recorded predators and wildlife prior to the 1080 drop. Initial signs are that there are far fewer predators caught on camera after the drop.

There are thousands of images to analyse, but the first batch shows no cats in a six week period within the 1080 drop zone, although one cat is caught in a trap.

Twelve dotterel nests have been found by rangers, containing 35 eggs. Five chicks have also been spotted. If each egg hatches, the Southern New Zealand dotterel population could grow to 145, edging ahead of the number of feral cats rangers have trapped.

Even with the encouraging results, DOC warns that just one feral cat is capable of wiping out multiple nests in quick succession.

Despite the positive outcome there’s still simmering disquiet in the community. The yellow protest signs remain dotted over the island.

A video has done the rounds on Facebook after the 1080 operation taken by people who walked on and off tracks. It shows green pellets littering the forest floor and talks of dead insects and quiet forests without the call of kiwi. A dead deer, one of four found within the area deer repellent was used in baits, is shown. The video generates angry comments and is shared on Protect Rakiura’s Facebook page.

Darius Fagan is the general manager of Predator Free Rakiura. He’s grateful to the people who went out after the drop and found the deer and says samples were taken for analysis.

He’s also been on the ground in Stewart Island and has done walks in the bush after drops with locals, some in support of 1080 and some opposed to it, in order to hear each other’s perspectives on the operation.

During the walks they stopped frequently, to do five minute bird counts. “We heard all of the bird species you would expect to hear on Rakiura,” he says. These included kākāriki, kākā and tūī. Signs of kiwi were visible and the group even stopped and drank from streams.

He’s not sure if the experience helps change minds or mend rifts.

“Some people might never be ok with a toxin being used in the environment, but they may be able to come to a place to accept it if they know the things they care about remain.”

If feral cats can be eliminated there’s a chance dotterel may be saved from extinction.

"If an animal went extinct in our lifetime my grandkids would say, ‘why did you not try and save them?’ I just want to be able to say that we did," says Fagan.

For now, the network of trail cameras will remain in place, the goal is to learn how long it takes the cats and the rats to reinvade the breeding sites.

When they do, 1080 may be the solution turned to again.

Southland District Councillor Jon Spraggon lives on the island and is a regular at the South Seas Hotel. He’s watched the small community become splintered on the topic. Some things, like the shoulder-barging incident, were blown out of proportion, he says, but he also feels tensions could have escalated to a point where laws were broken.

From some quarters there’s suspicion about some of the monitoring results released by DOC, but for the most part the conversations about 1080 have died down, he says.

However, he doesn’t think rifts have healed, or that the animosity toward the use of poison has vanished.

“I think it’s just festering underneath.”