After a brief period during which the traffic lights display a bright green person walking, everything goes red and little bit angry.

Anyone who has ever crossed the road knows the moment, and has experienced the sharpening tension.

From this point, a red standing person flashes and all those people hurrying the short distance to safety know their window is closing. Traffic will begin to roar through this space again soon. It is time to get out of the way.

It's messaging designed to keep us all as safe as possible, but it's not particularly friendly.

Assoc Prof Sandra Mandic would like that to change, for the green signal for pedestrians to stay green. Flash, yes, but stay green.

It's one small way, the University of Otago researcher says, in which we could begin to return our cities to some sort of balance, green-lighting active transport so urban environments are slightly less car-centric.

The suggestion comes in a new report released this week by Prof Mandic and her national and international collaborators in The Active Living and Environment Symposium (Tales) initiative. Turning the Tide - from Cars to Active Transport was unveiled this week in Wellington and Prof Mandic, one of its lead authors, is on the road selling its ideas up and down the country.

The headline goal of the initiative is to halve our reliance on car trips by 2050, shifting us instead towards active modes; walking, cycling and public transport.

"The report brings out the stark reality that the choices we are making in how we get from `A' to `B' are harming us and our environment," Prof Mandic says.

She's concerned that the way our cities are set up creates obstacles to getting the 150 minutes of moderate intensity physical activity we are meant to do each week. Which can be a matter of life and death.

"This [exercise] reduces our risk of premature death by 30% and reduces the risk of development of cardiovascular disease, cancer and diabetes," Prof Mandic says.

Most of us don't manage it.

It is the least discussed but perhaps the most pervasive negative impact of our transport system, the report argues.

Indeed, we appear to be spending more time sitting behind the wheel.

The New Zealand Household Travel Survey 2015-2017 found that on the average day, 81% of New Zealand adults reported no walking for transport and 98% reported no cycling for transport. Cycling to secondary school has plummeted from 19% in the 1980s to 3% in 2014.

And then there's the almost 400 people who die in traffic crashes every year.

One of Prof Mandic's collaborators in the Turning the Tide project, transport consultant Andrew Jackson, says the only mode of transport that increased its share between 1988 and 2014 was car use.

"This natural pressure to use our cars over other means of transport continues, with rapid growth in the number of kilometres driven by New Zealanders since 2013," he says.

On top of the health costs, there's the environmental burden. Our reliance on fossil-fuelled transport means we pump 14billion tonnes of carbon into the atmosphere a year, the report says. That's 17% of the country's greenhouse gas emissions. Then there are the 300 premature deaths each year due to poor air quality, and the mountains of waste produced, including tyres.

It's not a cheap system to maintain either, all those roads.

The report makes several recommendations.

The importance of active transport must be written into the Government's priority setting documents, the researchers say.

National targets should be to double the proportion of walking trips to 25% of all trips by 2050; to double the proportion of cycling trips each decade so that 15% of trips are by bicycle by 2050; and double the proportion of trips by public transport each decade to 15% of all trips by 2050.

As a result, travel by car would fall from 84% of all trips in 2018 to 45% by 2050.

To get there, the Government should embark on a programme of education and promotion of active transport; commit to designing cities for people, not for cars; and the regulatory system needs to encourage active transport, the report says. In terms of regulation, small things could again make quite a difference; the report, for example, suggests an enforceable minimum gap when passing cyclists.

But there are bigger-ticket items too. The report suggests an interconnected network of cycleways linking cities and suburbia, alongside a crowd-sourced national bike parking locator app and investments in high-quality bike parking design.

"Without this clear commitment, the inexorable tide of cars will continue to rise in New Zealand!" the report contends.

"This report is basically saying, we need to think about whether we are serious about this, whether we really want to make this change or not," Prof Mandic says.

In setting the targets, the Tales group aimed for the achievable.

Doubling walking by 2050, for all trips, seemed about right. Because cycling rates are so low, nationally, a goal of doubling rates every decade seemed a sensible way forward.

There was no particular data driving those figures, Prof Mandic says, and many factors will influence them over a period of 30 years. New techologies such as e-scooters and e-bikes are already making their mark and it is not possible to guess what might come next. The report does not, for example, address the possibilities of autonomous vehicles. Prof Mandic says there simply isn't the data on how autonomous vehicles might impact active transport.

"It's not looking very promising but that's not something we can include in the policy recommendations at this stage because we just don't have enough evidence."

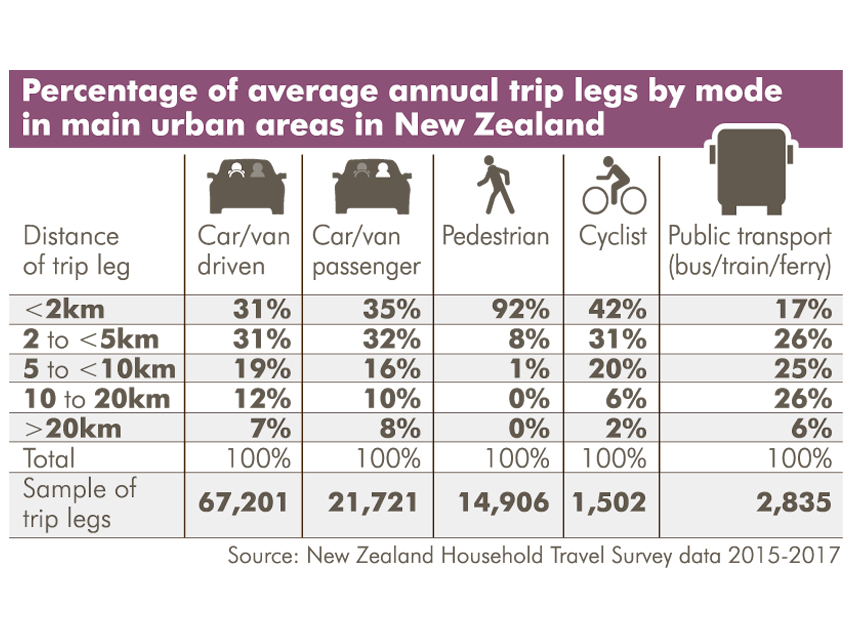

The data the Tales group did have includes figures on what sorts of trips cars are doing now.

Almost two-thirds are for journeys of less than 5km, almost a third for less than 2km. All could conceivably be replaced by cycling, and a good many by walking.

But Prof Mandic says it's not quite that simple. Some trips cover multiple purposes, involving several people, others are made by people too frail to walk, and topography comes into it as well.

"What is a reasonable distance for cycling in Dunedin would be quite different from what is a reasonable distance in Christchurch," she says.

They tried to be realistic.

"Some people are saying that the targets are not ambitious, if you consider the time frame of 30 years, because we need to act now."

For the purposes of comparison, a goal of the Dunedin City Council's 2013 Dunedin City Integrated Transport Strategy is to increase the percentage of Dunedin census respondents who cycle, walk or take a bus to work from 16% at the 2006 census to 40% by 2024.

The Tales group's work is not an attack on the motor car, Prof Mandic says.

"The report is not about demonising the car. We are not trying to say the car is bad, we don't want to remove all the cars from the road at all. It is just trying to find a healthy balance in modes of transport that would create or contribute to the health and wellbeing of New Zealanders, and the health of our environment."

Some trips will still need to be done in a car, even if moving a little more slowly.

"One of our priorities is building cities for people rather than for cars. And that's where we can look at our urban design and also regulations that we make, how can we make our cities more liveable."

Areas in town that are 30kmh zones would go a long way. It would make for towns that are designed as great places to be, rather than great places to move through in a car.

The report cites the Treasury's Living Standards Framework, which identifies four "capitals" necessary for a healthy society; human, social, natural and financial/physical.

As well as positively impacting on human and natural capital - promoting healthier humans and a healthier environment - active transport also contributes to social capital, Prof Mandic says.

People interact more with their neighbours, with their neighbourhoods, and with nature when they are out walking or cycling.

It's also good for local economies; people using active transport might spend less on each visit to a local business but they'll visit more often.

Achieving this sort of change involves addressing the social environment, she says.

"So what is our environment around us suggesting? And it is not our built environment, it is what our peers are suggesting, what our workplaces are encouraging, what kind of mode of transport. For example, for young people, what kind of environment or encouragement we provide for walking and cycling. All of those factors influence how people travel from place A to place B."

In the case of school pupils, something as simple as a school's policy on bringing laptops can influence how they arrive at school. Even the perception of a heavier bag can impact negatively on walking and cycling.

Prof Mandic admits that alongside education and promotion around active transport there will need to be measures to curb car use.

"There are a lot of examples from around the world where the changes have been made by reducing the parking," she says.

"Some cities, like Copenhagen, are progressively reducing parking by approximately 3% a year."

Other places have grasped the nettle more firmly still. Pontevedra, in Spain, a town of not quite 100,000, simply banned cars from the centre city, and saw a reduction in car use of 70%. Now, 80% of children there walk to school independently.

Prof Mandic notes that car-free city centres are actually quite common elsewhere, as are pedestrian crossing signals that stay green.

"That is actually present in a lot of other European countries.

"It is communicating a certain message to pedestrians that they matter."

It is part of a societal change, an understanding that we need to share the road, she says.

"It is not about building cycle lanes on every single road, it is not about having the footpath along the highway. It is about, we have a limited space and we need to be more comfortable that we need to share that space and that other road users also matter."

The Ford Ranger. Photo: AP

Vehicle numbers and use increase

The Ford Ranger. Photo: AP

Vehicle numbers and use increase

We do love our cars.

Ministry of Transport figures show there were 4.1million vehicles in 2017, an increase of 23% over 10 years. Light four-wheel vehicles made up 93% of the vehicle fleet.

That means there are almost 800 light vehicles per 1000 people, the highest level ever.

Vehicle kilometres are also rising. In 2016 they increased by 4.6% to more than 45billion kilometres. Each New Zealander travelled on average 9683km, the highest since 2007.

Commenting on the Tales report, Robert McLachlan, a distinguished professor at Massey University and the New Zealand Centre for Planetary Ecology, noted that the fleet jumped by 180,000 in 2017 alone.

"Fuel efficiency of the fleet is hardly improving. Altogether, transport emissions rose by 930,000 tonnes of CO2 - a 6% jump in a single year," he said. "This trend continues. Although final emissions figures are not yet in, the fleet grew by another 140,000 vehicles in 2018."

Our cars are also getting bigger, as the popularity of utility vehicles continues. Five made last year's top-10 sellers. The Ford Ranger ute was the top seller again last year, shifting 9904 units, up 5.1% from the previous year.

"This vehicle has truly changed the way Kiwis use this once farm-only vehicle, with it now also being used as a family wagon," the AA notes.

What they are saying

Some are already calling the goals in the Turning the Tide report modest.

Among them is Prof Alistair Woodward, a University of Auckland epidemiologist, who says doubling the proportion of walking trips should be achieved much sooner than 2050.

"The big challenge is political, because the car has been the dominant transport culture for 50 years," Prof Woodward says. "For this reason, anything that even appears to threaten the place of the car provokes strong opposition."

Dr Imran Muhammad, an associate professor of transport and urban planning at Massey, says to achieve the targets, "we need to go ahead with a few more sticks".

"Not only do we have to make driving difficult, but we also have to develop a quality walking, cycling and public transport network as well."

The report

Assoc Prof Sandy Mandic will present her report at the University of Otago Centre for Sustainability seminar room, 563 Castle St North, on Tuesday, May 14 at 1.30pm.

Comments

So cycling trips equal about 1 to 1.5% of all travel.

The Victorian (Aust) TAC, similar in function to the ACC, stated today that 20% of all road injuries occur to cyclists. The Hobart hospital published data about 2 years ago that over 70% of all cyclists injuries came from crashes that involved no other vehicles or people.

It would be interesting to see the stats for NZ road injuries. Maybe then we could see just how inherently dangerous and expensive cycling is. Expensive not just in creating bikeways but in medical treatment and wages, ACC costs we all pay for.

Maybe if people had some real data to see rather than just articles telling us to get off our butts, we might better understand the impact of this current bike mania.

Maybe only 1% of road users are cyclists and they account for 20% of road injuries. Maybe 70% of cycling injuries did not affect other road users but it does not mean that they all happened on perfectly empty roads or dedicated cycleways (probably quite the opposite). The only 'inherent' truth here is that existing roads can't be safely shared between motorists and cyclists - and that's why separated cycleways are being built.

So One wonders why most of my comments are not posted.

Without reading the full report this comes across as a piece of attempted social engineering rather than a rigorous piece of social environmental research. It ignores so many basic, but essential underlying factors.

A sizable part of the population have physical limitations that will naturally increase with age. Yes, we need to encourage exercise but we need to be realistic. Most of Dunedin's (and many other cities) population do not live within easy walking distance of the main centre or have easy access to shopping facilities. Public transport in Dunedin, and NZ in general, is minimal so that isn't really an option and won't be for the forseeable future.

Ignoring future transport developments is inexcusable. Electric cars are slowly making inroads as a temporary solution but will soon be overtaken by hydrogen technology already being developed by Hyundi and Toyota amongst others.

Overall this is a good example of academic research being used as a vehicle to peddle the views of the authors rather than the real facts.

Agreed.

In what sense is public transport an "active travel mode"?

The primary impediment to pedestrians is not cars — which largely behave predictably and in their own space — but quasi-vehicles such as bikes and scooters, the riders of which can be relied on to behave unpredictably and selfishly, and take up pedestrian space. Ironically, this fixation on "active transport modes" is pushing out the most active mode of all.