(DPAG Rear Window)

They are cruel is a queer, decolonial video work by Turanganui Gisborne-based artist and writer Georgina Watson (Ngati Porou, Moriori, Ngati Mutunga). In this work, Watson intentionally defamiliarises settler subjectivity by engaging with modernist writer Katherine Mansfield’s (1888–1923) short story, Summer Idyll (1907). Cinematically, Watson estranges settler culture by deploying a deconstructed colonial villa as a set erected in a grassy, fenced paddock.

By using drone technology, vertical distance clearly reveals the cross formation that structures the four rooms of the set and the centrality of Christianity to empire and colonisation — including that of the Victorian era. Fittingly for a set, there are no external walls on two sides of each room, which enables the camera and viewer to observe the carefully chosen accoutrements of Victorian and settler living: a wrought iron bed, an enamel mug. However, and equally appropriate as a form of critique, the absence of walls serves as an exemplary baring, even a wrenching open of settler memory, nostalgia, and museum diorama.

Watson’s decolonising work is intensified by her use of dialogue from Mansfield’s Summer Idyll which is reportedly drawn from Mansfield’s relationship with "Maori socialite and academic Maata Mahupuku" (Ngati Kahungunu, 1890–1952). While a cross-cultural lesbian or queer relationship is less controversial today, it adds a layer of complexity when considered retrospectively. Or perhaps the centrality of a lesbian encounter presses for queer visibility in the quest to decolonise Aotearoa.

(Reed Gallery, Dunedin Public Library)

In 2002, a university library I was working at underwent a process of removing and binning all the dust jackets from their collection. Unable to comprehend what felt like an act of desecration, I placed a large cardboard box at check-in with a sign asking other librarians to put the jackets in the box rather than the bin. For a time I was able to hold on to these salvaged cultural artefacts, but in the end, I was overwhelmed by the volume and without the controlled storage required to preserve them. So when I encountered the exhibition "Jackets Required" at the Reed Gallery, it was a relief and pleasure to see the material culture of the book in all its aspects not only preserved but receiving the aesthetic attention it deserves.

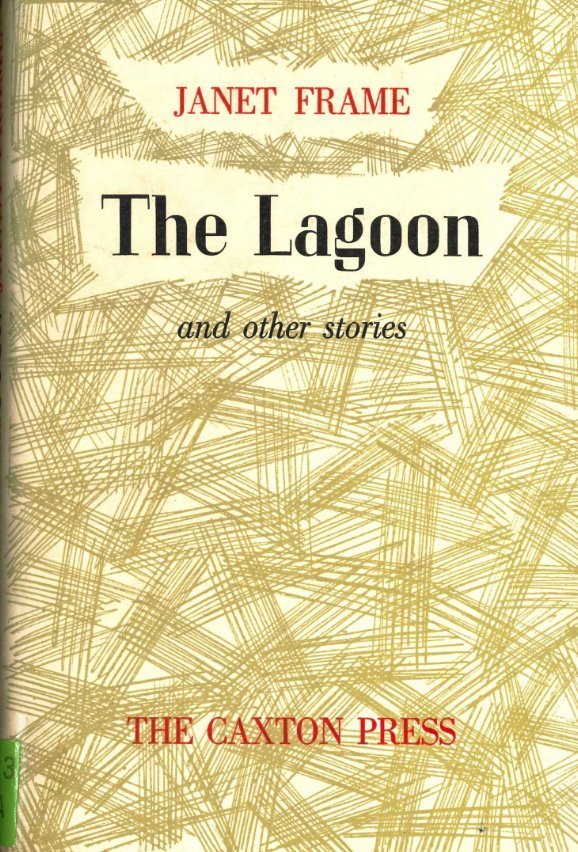

Curator Julian Smith has organised the dust jackets primarily by genre: poetry, drama, history, biography, memoir, but also by publisher, particularly the significant early publishers such as Reed and Whitcombe. Literary giant Janet Frame has a case dedicated to her and there are several organised by gender that celebrate "notable" and "award-winning" male and female writers.

Following Smith’s selections, the 1950s and 1960s appear to be the strongest decades of the dust jacket in the material, cultural life of the book and a witness to the talented artists who created small works of portable art.

The small exhibition "Keep it Glassy" at Tuhura Otago Museum responds to the United Nations’ Year of Glass. Although designated for 2022, there are still a couple more months to view Keep it Glassy, which is installed in the stairwell (two floors) of Tuhura.

The malleability and versatility of glass make it an exemplary candidate for material of the (last) year, as this select presentation of objects, tools, jewellery, and fine dinnerware manifestly show. Drawn from diverse cultural and geographical locations, the exhibition includes candlesticks from England (c.18th century), a glass-sided kerosene lantern "used for evening meetings of the Otago Institute" (undated), glass bead necklaces from Egypt, Venice, "Persia", "Africa" (various unspecified dates), and a gilded blue glass goblet from Germany (18th century) among others.

Two artefacts that stood out for different reasons were "Pressure-flaked glass Kimberley points" described as "Aboriginal tools" from the Kimberley in Australia (early 20th century) and a coloured glass anemone from Germany (late 19th century). Aboriginal people have recently had stolen artefacts returned from New Zealand cultural institutions. These treasures appear to have been purchased by a fund. A quick search revealed the Kimberley to be home to the Ngarinyin people, who represent about sixty clans who belong to four larger nations. It is not clear which clan or nation made these exquisite glass points.

Similarly beautiful is the Urticina crassicornis, a coloured glass, mottled sea anemone that served as a teaching model!

By Robyn Maree Pickens