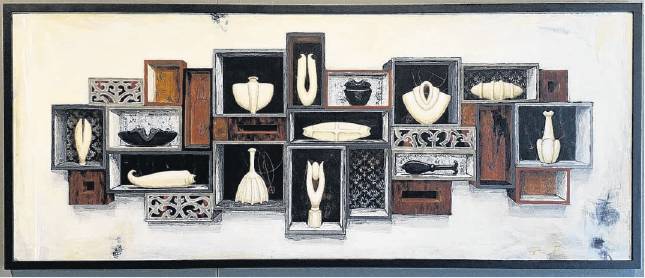

‘‘Nature Morte’’, Megan Huffadine

(Eade Gallery, Clyde)

Megan Huffadine's work has long paid homage to Wunderkammer, the cabinets of curiosities that collated artefacts from geology, natural history, archaeology, antiques and artworks.

Wunderkammer were a forerunner to our modern museums, conveying ideas, preserving history and highlighting individual wealth. In previous collections,

Huffadine focused on sculpture, creating her own cabinets of wonders, arranging shapes and symbols, tools and vessels like the treasures of a past world, real and imagined. During last year’s lockdown, her journey turned towards her painting, combining symbols and visual language with the tradition of the still life.

Like the Wunderkammer, early still-life painting frequently contained an allegorical message, or a display of riches. In modern art, it became as much about the structure of the composition, the movements of the brush, as it did the subject matter.

It can turn the most mundane collection of everyday objects into something magical and beautiful; however, there is nothing commonplace about Huffadine’s subjects.

By painting images of her own sculptures, it’s as if the past works have moved beyond a looking glass, preserved forever in a world of their own. Some of the painted boxes have the effect of a wallpapered rear wall, a definite enclosed space; while others extend into blackness and infinite possibility. The artefacts within conjure images of a magical past, a touch of fantasy and the shadows of the unknown.

‘‘Land - Recent Work’’, Eric Schusser

(Hullabaloo Art Space, Cromwell)

‘‘Colour catches the view and pleases the eye,’’ writes photographer Eric Schusser of his latest collection, ‘‘but black and white conveys the soul and pleases the heart.’’

Standing surrounded by his photographs, a series of windows on to majestic vistas and calm havens, you will understand entirely what he means.

The South Island is full of glorious views, a different type of beauty everywhere you look; it’s always spectacular when rendered in full colour - but Schusser’s black-and-white images become far more than a photographic record of a stunning landscape.

Somehow, in the absence of colour, an intense quiet seems to drop over each scene, everything becomes stills, and you find yourself looking into it, rather than merely at it.

The time of day, even the year in which the photograph was taken, shrinks in significance as you mentally fall into each scene, engulfed in a sense of timelessness, part of an eternal story.

You might be standing on the banks of the Clutha River Reflection now, 10 years in the past or 100 years in the future.

As you look through the bare tree trunks of Park Fog #1, gazing into the encroaching mist as the trees in the distance slowly slip away like ghosts - or emerge from the fog as you walk forwards into clarity and cognisance - endless possibilities unfold.

The scenes might be tense and eerie, or it could be utter serenity and peace, depending on the mindset you bring to what you see.

‘‘The Earl Street Journal’’, various artists

(Milford Galleries, Queenstown)

Sculptor Neil Dawson excels at the juxtaposition of ephemeral subject matter and industrial materials, but his series of oversized feathers is perhaps the most striking.

In nature, we often come across discarded feathers, such a mundane sight, yet so intricate and extraordinary when examined up close.

Each feather has traversed tremendous stretches of land and sky, protected its bearer against the elements, offered camouflage for survival, a remnant of flight and fight in one weightless object.

Dawson’s painted polycarbonate and aluminium feathers capture the elegance and delicacy, the wonder in every sleek line, but also the durability and strength behind that deceptive frailty.

Natchez Hudson has an eye and hand that can reproduce a scenic view with photographic accuracy, but his fascinating canvases never allow you to forget that you are looking at a two-dimensional image.

A mountain is sliced in half and flipped upside down, photo-realism interspersed with large blocks of solid colour, overlaid with painted lines and geometric shapes.

The work opens an important door into the continuing evolution of landscape art, an examination of the role it plays in our national art history, shifting the viewpoint and shaking up a comfort zone to new possibilities.

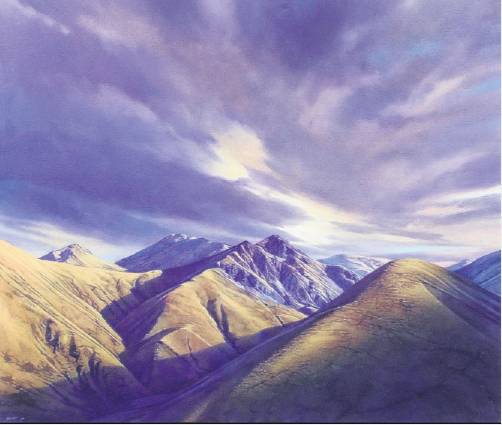

Alongside that are pieces such as Bruce Hunt’s intensely realistic landscapes, more traditional in composition, yet also making your breath catch in their beauty.

Ultimately, this year’s Earl Street Journal exhibition pays testament to how many different paths there are in art, and how much we need every creative voice.

![Poipoia te Kākano [installation view]. Allison Beck, Megan Brady, Kate Stevens West, Jess...](https://www.odt.co.nz/sites/default/files/styles/odt_landscape_small_related_stories/public/story/2025/02/1_poipoia_te_k_kano.jpg?itok=ssJ8nxyx)