A rare New Zealand desert parsley and a Slovenian endangered beetle might not have much in common on the surface, but dig deep and you will find they both tell a story about the nations they come from.

Each is also key to a journey that has led London-based, Slovenian artist Jasmina Cibic to exhibit in Dunedin.

In Cibic’s research she found the cave beetle Anophthalmus hitleri was discovered in 1933 and named by an admirer of Hitler in 1937. After National Geographic published an article on the insect in 2006, collectors of Nazi memorabilia began to hunt them down, resulting in this small, blind creature joining the endangered species list.

Cibic, representing Slovenia at the 2013 Venice Biennale, commissioned more than 40 international entomologists and scientific illustrators to produce illustrations of the beetle, which she used to paper the walls of a room in "For Our Economy and Culture".

This exhibition was viewed by Dunedin Public Art Gallery curator Lauren Gutsell, then an attendant at New Zealand’s Venice Biennale pavilion.

"I thought it was such a strong exhibition. It was the first time I’d seen her work in person and the experience definitely gave me an immediate and direct insight into the processes in which she operates, explores and interrogates different relationships between national culture and the soft power mechanisms of art and culture."

Gutsell, who is now a curator at the Dunedin Public Art Gallery, kept track of Cibic’s work over the years and in 2019 approached Cibic with the idea of travelling to Dunedin to exhibit here.

However, Covid interrupted and the uncertain future led to the DPAG and Cibic deciding to continue the project. It meant Cibic working from London, keeping in touch with the gallery by email, Zoom and phone. Gutsell says what was most important was enabling Cibic to continue the site and context-specific aspects of her work. It was decided to exhibit her film The Gift alongside a site-specific installation.

"It was really important her practice continued in that way while working remotely. While it is hard for an artist to work via distance, what we have learnt is that it is possible, you just work in a different way."

For Cibic, audience is really important so it is her first point of thinking when planning exhibitions.

"It is why I have part of a project that speaks directly to the site, to the institution or the city as much as I can. Not having been able to travel to Dunedin, it is a pandemic version of a site-specific project carried out via Zoom."

She wanted to continue playing with the idea of how culture is used to represent a nation in the exhibition.

"Somehow it has become the central interest of my practice for two decades. The relationship between culture, nation building and soft power, so how architecture, theatre, dance are utilised in those contexts as instrumentalised tactics of government."

The three-channel film The Gift is what Cibic calls the "centrefold" of the Dunedin exhibition. It is a dystopian drama presenting a fictitious competition to find the right gift to heal a nation.

"There was an unwritten contract between the government, the citizens and cultural providers, which was torn up with unprecedented speed during the pandemic and I wanted to study this closer."

The film features "three allegories" — an engineer, a diplomat and an artist — who pitch for why their vision of culture could heal the nation. They make their pitches to four female characters of freedom who guide, give direction and suggest ideas of what they need to do to achieve their goal.

"They are quite unrealistic and unachievable."

Many of the settings for these pitches are filmed in places of power such as the Oscar Niemeyer’s French Communist Party Headquarters in Paris (a gift from the architect to PCF), Palais of the Nations in Geneva (composed from gifts by the international community), Museum of 25th of May Belgrade (a gift to Tito from the nation), and Mount Buzludzha Bulgaria (a gift from the nation).

Some of these places open their doors gladly, others do not, but Cibic is careful to ensure that they are aware she aims to open conversations, decolonise and create a feminist narrative with her work.

"It’s a slow conversation — usually they are quite open to it. Sometimes it surprises even me. They know questions have to be asked."

In other projects it has allowed her to access material never seen before, such as song scores and flag designs given to the League of Nations during World War 2.

"They were not super-incredible music pieces but it’s the story which is so important, as it lends itself as a perfect metaphor for questioning the partnership between culture and national power."

The Gift is built from what Cibic calls "historical ready-mades" she discovers through researching archives.

She finds and draws together transcripts, letters, maps, artworks and plays that have been gifted during times of national and political crisis in the 20th century.

"These historical ready-mades all bind together to suggest a new potential narrative which condemns a century or more of humanity’s drive to use culture as a token of national healing."

The concept of a gift also appeals to Cibic, who won the Jarman Award for artists working with moving images last year, as by its very nature it is not returnable so there is an expectation of a "counter gift" being made in return.

"I like the optimism of the idea that the counter gift is the social discourse that comes with circulation of meaning and exchange that culture provides."

So when it came to thinking about exhibiting in Dunedin, the obvious place to start was by digging into the archives and history of the city and its institutions, she says.

"Because I’m quite interested in soft power, the obvious place to start was the construction of the city and the gallery which was also a gift. "

"The collection was created by gifts from benefactors who had quite clear ideas on what they deemed most representable for these imports. So I started concentrating on what they were bringing into these cultural landscapes and what did they expect in return."

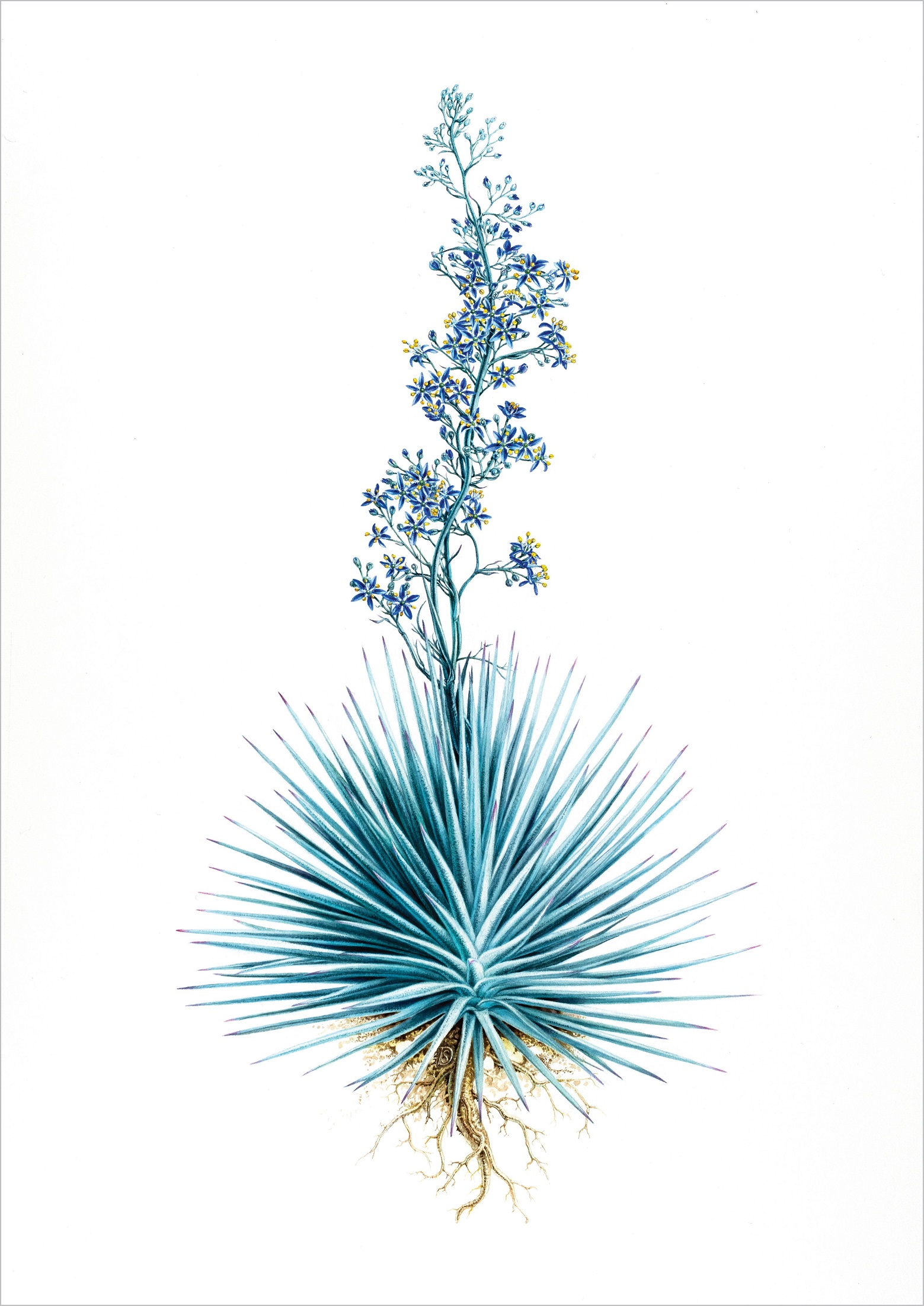

She discovered an "interesting parallel" between the export of culture to the colonies and the import of new flora to Europe, obviously named by the European colonisers — such as Eucalyptus banksia named after Joseph Banks, Saccoloma sloanei after Hans Sloane and Lomatium cookii after James Cook.

"I focused on plants which were from New Zealand, Australia and South Africa — all new Europes, all which were rediscovered and renamed by agents of empire."

But Cibic also became "a little bit upset" when she realised the rules of taxonomy are that a plant cannot be renamed unless it is shown to be substantially different from the original.

"It’s the last platform of history that firmly resists decolonisation. This notion of giving names can also be viewed as a form of a gift that really cannot be returned."

Many of the historic figures the chosen plants were named after had dubious pasts, were slave owners or supported slavery, or very intrinsic within European sustained colonisation. Yet their names cannot be removed from these plants, some of which are nationally significant.

"The entirety of the contemporary art world has been going through a decolonist drive, working hard to attempt to decolonise itself and social, historical structures so it is an interesting moment to look at the most stubborn part of the language that within its own set of rules does not allow decolonisation to happen."

To illustrate this issue in the exhibition, Cibic invited 20 scientific and botanic illustrators from around the world to draw the plants solely basing their work on their Latin names and without seeking more information about the plant.

"It was a really beautiful collaboration that brought up some very important questions. Who does culture serve? Are we just illustrators of an imposed system of control?"

The illustrators created "amazing projections" of how these plants might look, speculating that the plants must have drawn the attention of the colonisers for specific purposes such as a use for pigment extraction or medicinal properties.

Alongside these, Cibic has created a series of drawings of the iron gates of botanic gardens in Europe where the specimens the agents brought back were planted.

Across these gates she has written slogans drawn from politics but originating within a botanical context, underlining the relationship between the two.

Phrases such as "rose garden strategies", which refer to diplomacy being carried out at home rather than travelling abroad.

"THE whole exhibition is really a platform for discussion — where do we sit today? How do we deal with last roots of language and systems that cannot be decolonised?"

For Cibic, who moved to the United Kingdom to do her masters at Goldsmiths University in London and "stayed", her practice relies on what she discovers in her searches through archives.

But she prides herself on being able to pull together institutions that would normally not work together on projects such as a research laboratory and a private collection.

"That’s the challenge, that is the beauty of working in a way not governed by imposed capitalist interests."

Thankfully, she says, there are some art museums that understand "that is where the magic happens".

"It’s all about relationships and communications, I think."

Much of Cibic’s drive and political focus comes from growing up in the former Yugoslavia and experiencing the first of the wars to hit the region as a child.

"My interests are for sure informed by the nature of my brutal awakening to capitalism when I was 10 or 11 after the wars."

It made her believe the current political systems were not sustainable and there should be a different way for the future.

"The art world provided that space for thinking speculatively and offered an opportunity to propose new systems of thought, even just as model."

Cibic mourns the clamp down in many places such as Hungary and Poland by right-wing governments of what is being show in museums. Slovenia had also come close to that by replacing all of the main directors of art museums and cultural institutions.

"Many of the European right-wing governments we are seeing now are really wreaking havoc on cultural capital, what is being presented to audiences at home and what is being sent out."

She continues to have "one foot in the Balkans" as she believes it is important to not just use material from her home country in her work and walk away.

"A lot of artists have gone abroad, using material and experiences from local traumas, playing the geopolitical card. I’ve made it my work mission to counteract that, working with the next generation, not just visiting archives and amazing spaces for source material but to really engage with them in a solidarity that proposes new future potentials."

Cibic, who has a daughter, intends to stay in the United Kingdom despite the challenges the art world is facing there.

Britain in post-Brexit times has shut down many of its collaborations with Europe and its galleries are focusing on local and national interests.

"It’s like we are in a 1950s playbook, but that’s the pendulum of history. You can moan about it or we can find partners to build a new ecosystem to weather the current political climate."