"Paradise of Imagination: Medieval and Modern Encounters",

(Dunedin Public Art Gallery)

The Middle Ages have been a subject of inspiration for artists ever since their end. Whether reimagined as a time of chivalry or a mysterious "dark age", the period still fascinates to this day.

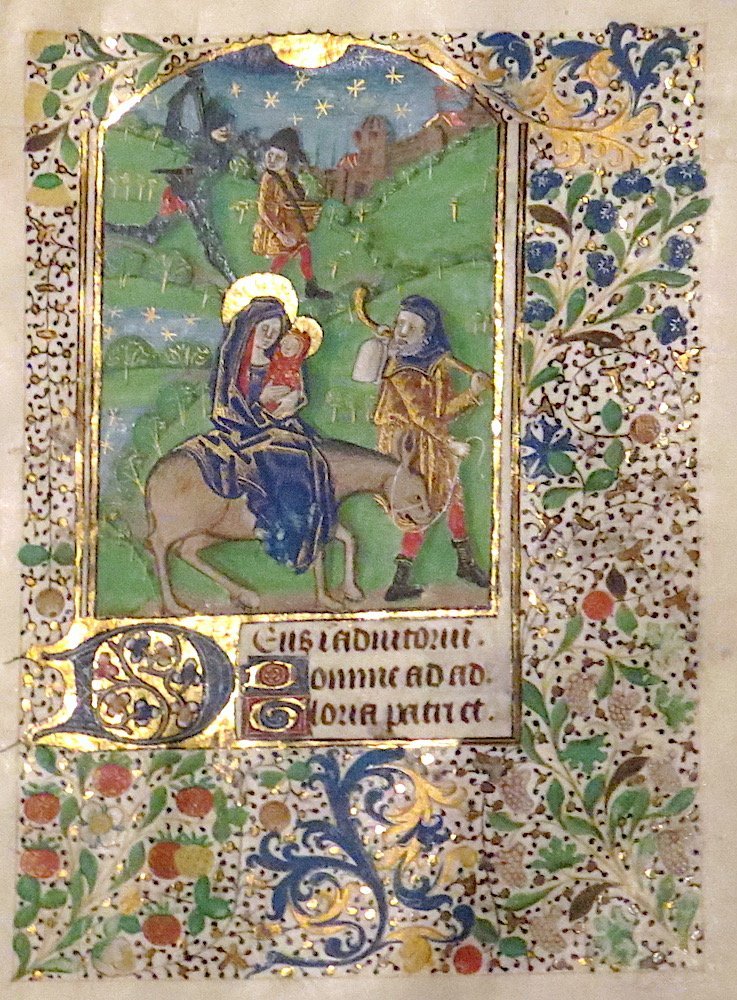

The exhibition "Paradise of Imagination" looks at interpretations of the era by artists from the period’s end to the present day. The exhibition focuses largely on three periods of creativity: the late Medieval era, the 19th-century revival in Medievalism, and current work reflecting Medieval inspiration. The first of these is represented by a series of beautiful illuminated fragments from prayer books and by a fine engraving by Albrecht Dürer.

A 19th-century revival in interest in Medievalism, led in part by the Pre-Raphaelites, informs the next group of works. Paintings by Edward Burne-Jones and George Frederic Watts excellently illustrate the revival, and in works by David Edward Hutton and William Morris we see the inspiration of illuminated texts.

The recent pieces more loosely interpret the theme, though in Roger Mortimer’s faux-Medieval New Zealand the inspiration is apparent.

Lonnie Hutchinson’s work is a paralleling of European histories with lines of whakapapa, and Marilynn Webb’s works reach out to the shared belief in the oneness of people and the earth found by Māori and also in European folk religion.

(Brett McDowell Gallery)

The art of the Medieval era is also one of the many touchstones which blend in the art of Jeffrey Harris, notably in its depictions of religious themes.

One of Dunedin’s best-known painters, Harris has carved out a powerful five-decade career, constantly changing and evolving, but repeatedly returning to a few central motifs: figures within a magic-realist landscape, faceless semi-nude characters interacting in aleatory groups, and above all the central religious image of the crucifixion. These symbols are used in Harris’ art as private metaphors, symbols with hidden intent, and important parts of some incompletely glimpsed narrative. Despite the deliberate, often wanton, roughness of the depicted characters, the sense of colour, image, and composition creates compelling art.

The images in the current exhibition date from the early 1970s, a time when Harris first became a full-time artist. We can see that even by this time, much of the artist’s style was already becoming solidified, though in the graphite works we can see the artist still experimenting and learning, notably in a study of Jean-Marc Nattin’s 1738 portrait of the Marquise D’Antan.

Given the painstaking slowness with which the artist is notoriously famous for completing works, to see such an array of Harris’s works together is a rare delight.

(Hutch)

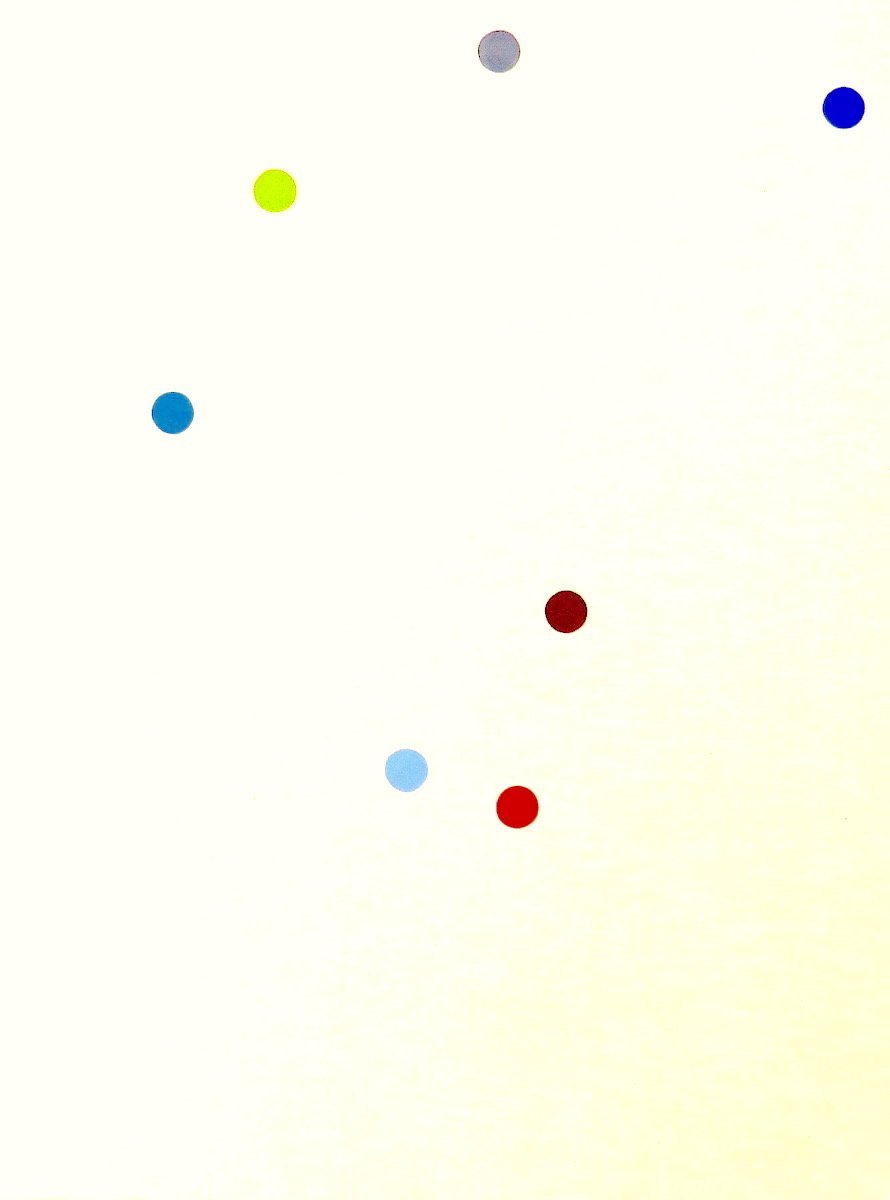

While the groups in Harris’ images may seem aleatory, for randomness it is difficult to surpass James R. Ford.

Ford’s work is an epitome of minimalism. His canvases are empty save for dots of uniform size, their colour and position dictated by computer program.

Despite the attractive austerity, there is wry philosophy here. The concept of "Six Times Seven", ostensibly six paintings each with seven dots, connects with the repeated discoveries of the numbers and their product (42) in culture. From Douglas Adams’ use of 42 as the answer to the ultimate question of the meaning of life, by way of Biblical references, and even the artist’s age, the works become a deliberate search for meaning. They are literal canvases upon which to project our pareidolic search for non-existent patterns. Since the exhibition was first planned, "6-7" has even become a popular, deliberately meaningless meme. The artist addresses the absurdity of the search for an understanding of the universe by presenting canvases that deliberately have no meaning ... unless, that is, the lack of meaning is itself the meaning.

In an earlier exhibition, Ford stripped away the subtlety to present a sculpture of a dangled golden carrot. Here, the works become metaphorical dangled carrots, chances, no matter how obscure, to discover a meaning to it all.