‘AVERAGE OF 3 SPARKS’ — PAULA COLLIER

The workers at Gillies MetalTech may have raised their eyebrows when Paula Collier handed them paper to cast but they gave it a go.

"I think they really enjoyed that because it ... made them have to figure out different ways of doing things with a practice that they’ve worked with for decades," she said.

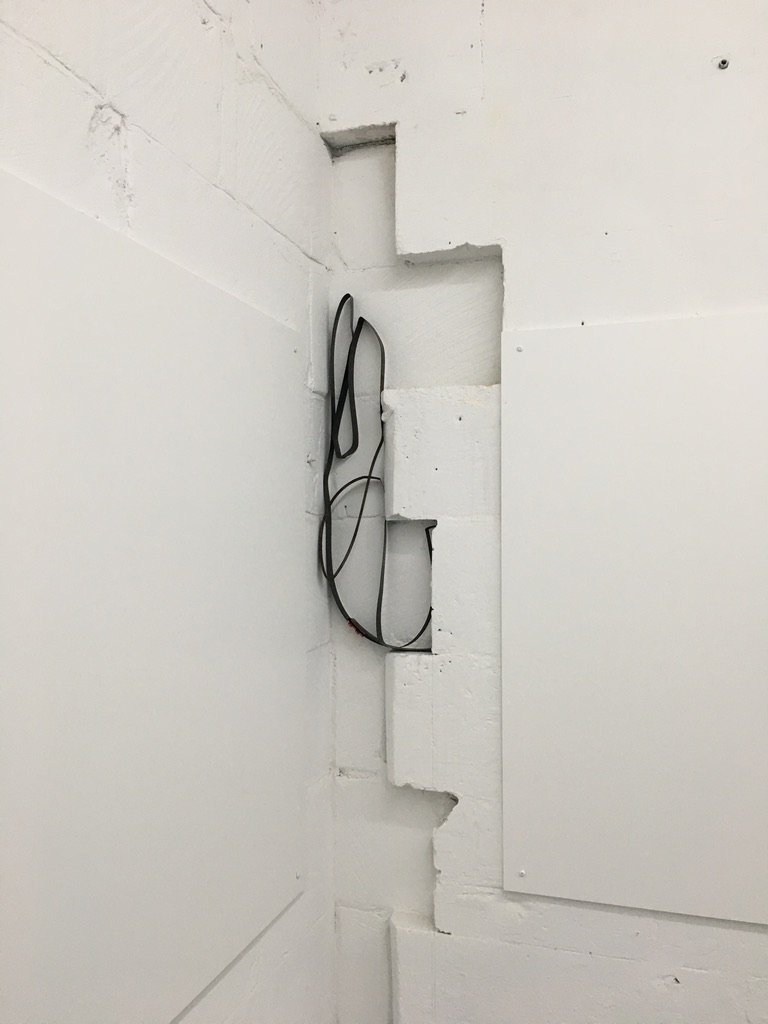

She ended up taking a two-pronged approach based in the old dentistry building on the site which used to house workers from Tonga who worked at the foundry. One project involved bringing scrapped materials from the foundry into the building and creating designs which responded to the building. For the other, she cast fallen ceiling slats in metal which she then exhibited in the gallery.

"I’m really interested in the autonomy of materials and the way that materials have their own intention in life and also the invisibility of things that are just lying around and connected to our lives that we don’t really notice."

She called the projects "Average of 3 Sparks", referring to the electric testing method used to calibrate the chemical elements that make up molten metal for casting.

"It was really amazing ... to learn a new skill and have the ability to just work in the factory with people who are experts."

Part of her work involved using paper printouts from the metal testing they did before a pour. The white paper and plaster were used to create poles that reflected the decaying surfaces throughout the old buildings at the foundry.

"There was a really strong visual that I kept seeing everywhere of these curled, peeling wallpaper forms. I love the contrast of making something really fragile and delicate and white in this foundry environment. Everything’s heavy and dirty and dark and dusty."

She came back to her art practice a few years ago by doing her master’s at Massey University but continued her early love of using repurposed materials in her work.

"Initially I found that it was just a case of finding my own voice again because the film industry work is about realising someone else’s creative ideas.

"So I moved away from using fabric quite deliberately and ended up using a lot of paper."

"I found that there was a lot of shared language between the way I work and the way I’ve worked in film, doing screen printing and working with people with these processes and these materials."

The residency showed her that her years in film were not a negative as she had viewed them as they took her away from her art practice.

"I’ve since realised that it’s really benefited me in terms of I know how to work in a workshop environment, I know how to relate to people and communicate ideas that are creative, conceptual and practical ... It all feeds into my current practice."

‘I was like — ‘that’s it"

‘BARREL OF MONKEYS’ — ZAC WHITESIDE

An award he received for being the class clown in art school, the "Barrel of Monkeys Award", is what inspired Dunedin artist Zac Whiteside’s latest work.

"I started thinking, like, ‘what is a barrel of monkeys?’ I think there are things that are more fun than a barrel of monkeys. I mean, the game itself is incredibly repetitive. And it’s not exactly exciting. And then the term is meant to be this, like, chaotic, exciting, kind of if you actually opened up a barrel of monkeys, there’d be mischief and there would be things flying around."

So he set about thinking about what would make the toy into chaotic fun. The toy was the perfect object to cast at the Gillies MetalTech foundry during his Crucible residency as he thought he could easily upscale the game using a crane to play it.

The monkeys were essentially an "S" hook, an industrial shape, and he noticed at just about every stage of the foundry process a crane of some type was used.

"As I worked on the project, more and more things came that kind of reaffirmed why I should do it. So they feel like they could be a product out of the foundry."

For Whiteside, the residency was a chance to learn sand-casting, so it also worked as an object he could make over and over to get "really good" at the process.

"I made 15, and by the 15th one, I was actually, like, my mould making was significantly better."

The "monkeys" were cast in the foundry and then they were craned to be hung on a pole so they could be painted bright red.

The foundry’s crane driver had the first "trial" run at playing the game and managed to get seven monkeys.

"He said to me, ‘I’d be very impressed if you managed to get five because it’s a lot harder than it looks’. And so the first attempt I did with the crane, mind you, it’s my first time ever operating a crane, I did get five."

Another crane operator managed 11.

"He was absolutely legendary. He was getting double hooks. He was, like, hooking two on one arm and then he was, like, almost hooking four at once. It was astounding."

Whiteside also likes how the project highlights the skills tradespeople have, given some people look down on those who work in construction and other trades. Having worked many university holidays on construction or roading projects he understands the skill that goes into their work.

"I was just always quite drawn to bronze in particular as a material."

He went on to create four large concrete sculptures for Otago Polytechnic’s "Four Plinths" project as well as new editions of his "bit coins" featuring bronze coins with "bites" taken out of them, this time made of with silver and gold wrappers and a group show at Blue Oyster for which he made a series of steel-wool rugby jerseys.

In between art work, he worked on his photography and videography freelance practice and was part of a group that started artist-run gallery Pond, to help artists just out of art school, where he held his latest exhibition. They had since closed the gallery.

Now moving to Wellington, where he grew up, Whiteside has just secured an early career grant from Creative New Zealand. He will be creating a large-scale project which will end in a public performance.

"This time it’ll be a little bit less heavy. It’ll be incredibly light. I won’t give too much away but I’ll be exploring the housing crisis."