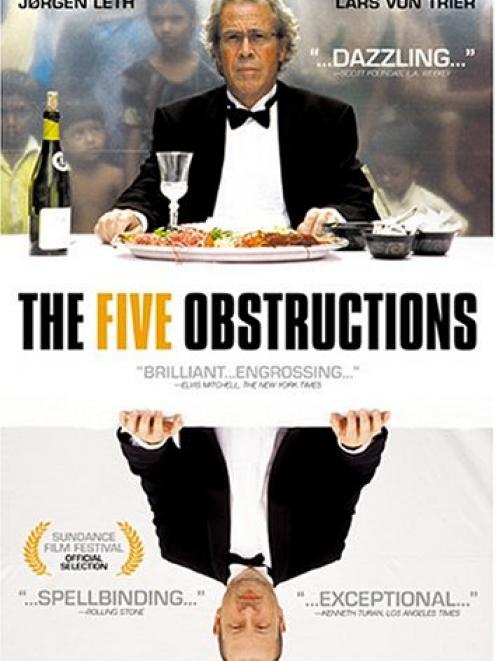

The Five Obstructions (2005) is a playful and profound documentary about a pitched battle between two giants of Danish cinema, Lars von Trier and Jorgen Leth.

The film's central concept is like something lifted from reality television and repackaged for film buffs.

Rather than being forced to swim with sharks or to eat live beetles, Leth is goaded by von Trier, his friend and former Danish Film Institute student, into remaking his seminal 1960s short film The Perfect Human five times, each time adhering to a fiendishly challenging set of ‘obstructions' posed by von Trier.

In the first of the five obstructions, Leth, famous for his long, uninterrupted, carefully observed takes, is told to remake the film in Cuba, with no set, and to ensure that no shot lasts for longer than 12 frames (half a second), a cut rate that would make even the most hyperactive MVT director take pause.

When Leth returns with a film of fluid, kinetic beauty, von Trier's resolve as a torturer hardens. "The 12 frames were a gift!" he says, before sending Leth off on his next odyssey, this time to ‘the most miserable place on earth'.

Von Trier is the enfant terrible of Danish cinema, a director famous both for his disregard for conventional cinematic rules (a musical-melodrama shot on shaky digital camcorders and ending with an execution, anybody?) and his tendency to devise fiendish rules and restrictions of his own.

The Idiots was filmed according to the ten ‘dogmas' of the Dogme 95 manifesto, which called for the abandonment of artificial lighting, set design, musical soundtracks and tripods, among other things.

Dogville and Manderlay were set in imaginary villages and shot in bare warehouses, complete with the mimed opening and shutting of doors.

Leth, by contrast, is bound by his own code of artistic conduct, what he calls the ‘ethics of the observer', requiring him to maintain a distance from his subjects and capture reality as it unfolds.

So to watch the games the filmmakers play with one another is to witness a war of ideologies. "Would you film a child dying in a refugee camp and add the words from The Perfect Human?" asks von Trier.

The film also offers a fascinating glimpse into the personal lives of the two filmmakers and the relationship between them.

Leth and von Trier both suffer from melancholy and depression, and an understated but ever-present theme in the film is the fact that Leth has been living a depressive and lonely life in Haiti as the honourary Danish consul, having retreated from the world of filmmaking entirely, and that von Trier is taking on the role of therapist here.

If von Trier is a therapist, he is seemingly from the ‘primal scream' school.

He has been described as sadistic by at least one of his leading ladies in the past, and his unabashed goal here is to break Leth, so that he can remake himself.

Will von Trier succeed in his goal of forcing Leth to ‘move from the perfect to the human?' I'll save you the pleasure of deciding this for yourself as you watch the fifth and most remarkable ‘obstruction'.

If you are interested in the ways that artists adapt, react and respond to adversity, weaving straw into gold, then this will be a real and rare pleasure.