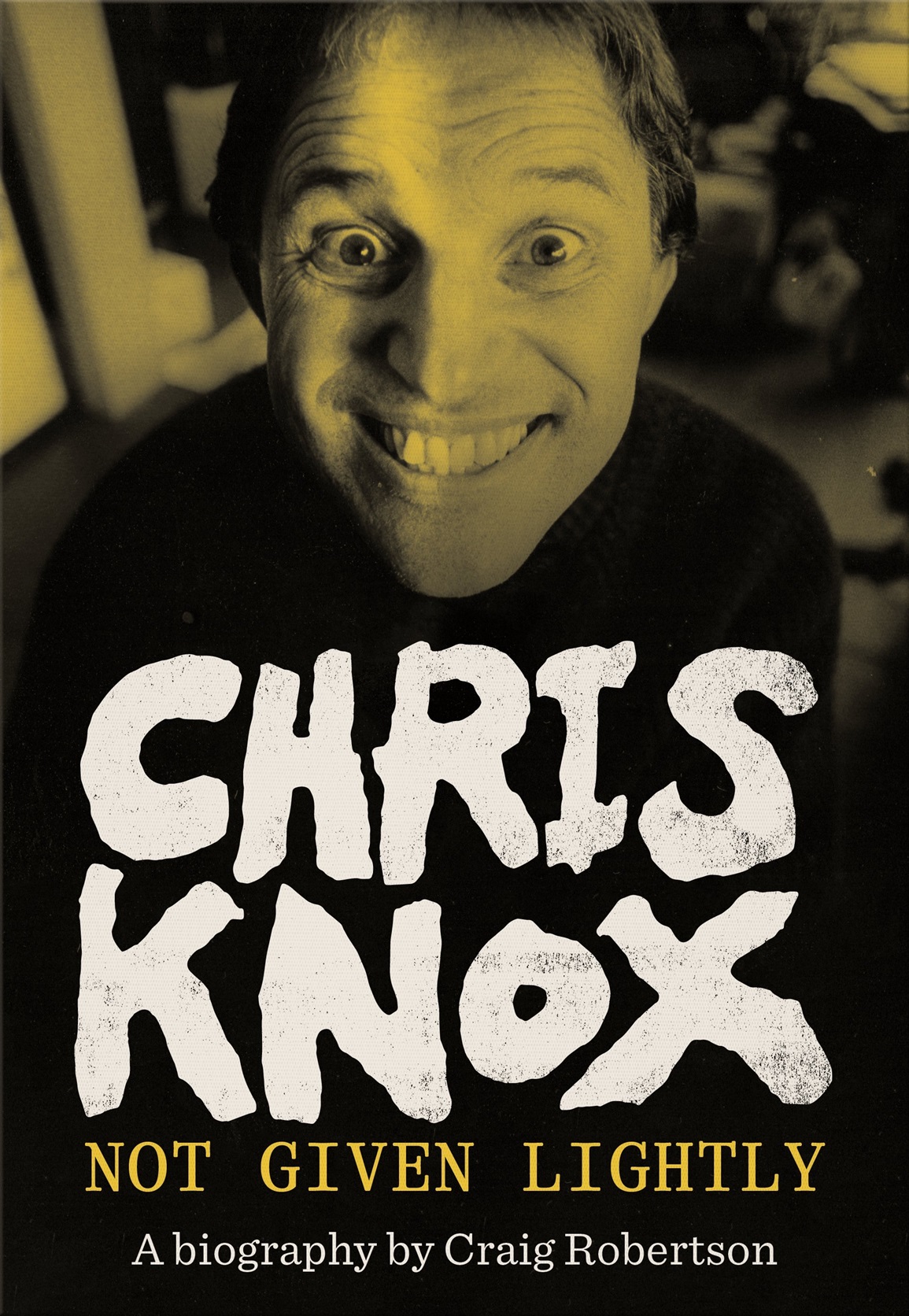

Honesty has remained a guiding principle for the creative polymath Chris Knox, his biographer, Craig Robertson, says.

So, in that spirit, he has an honest moment of his own, revealing ... he hates biographies.

"I honestly don't think I've ever completed a biography, other than when I was a kid," Robertson says of his reading habits.

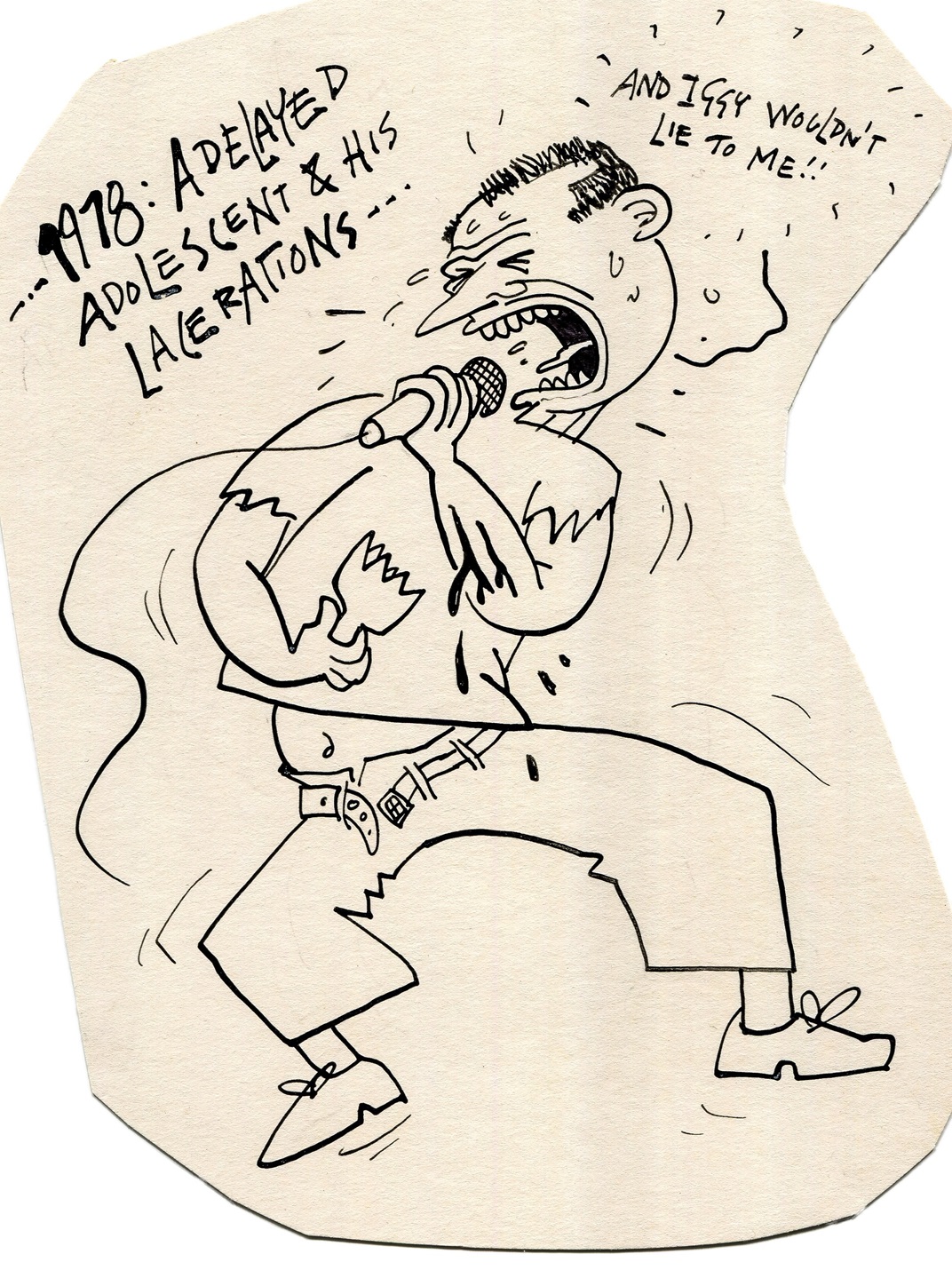

There are various ways to regard the admission. One might be to decide Robertson has just burnished his credentials to a high sheen, given Knox’s life of John Lydon-inspired iconoclasm and provocation across music, video, graphic art, writing ... and more.

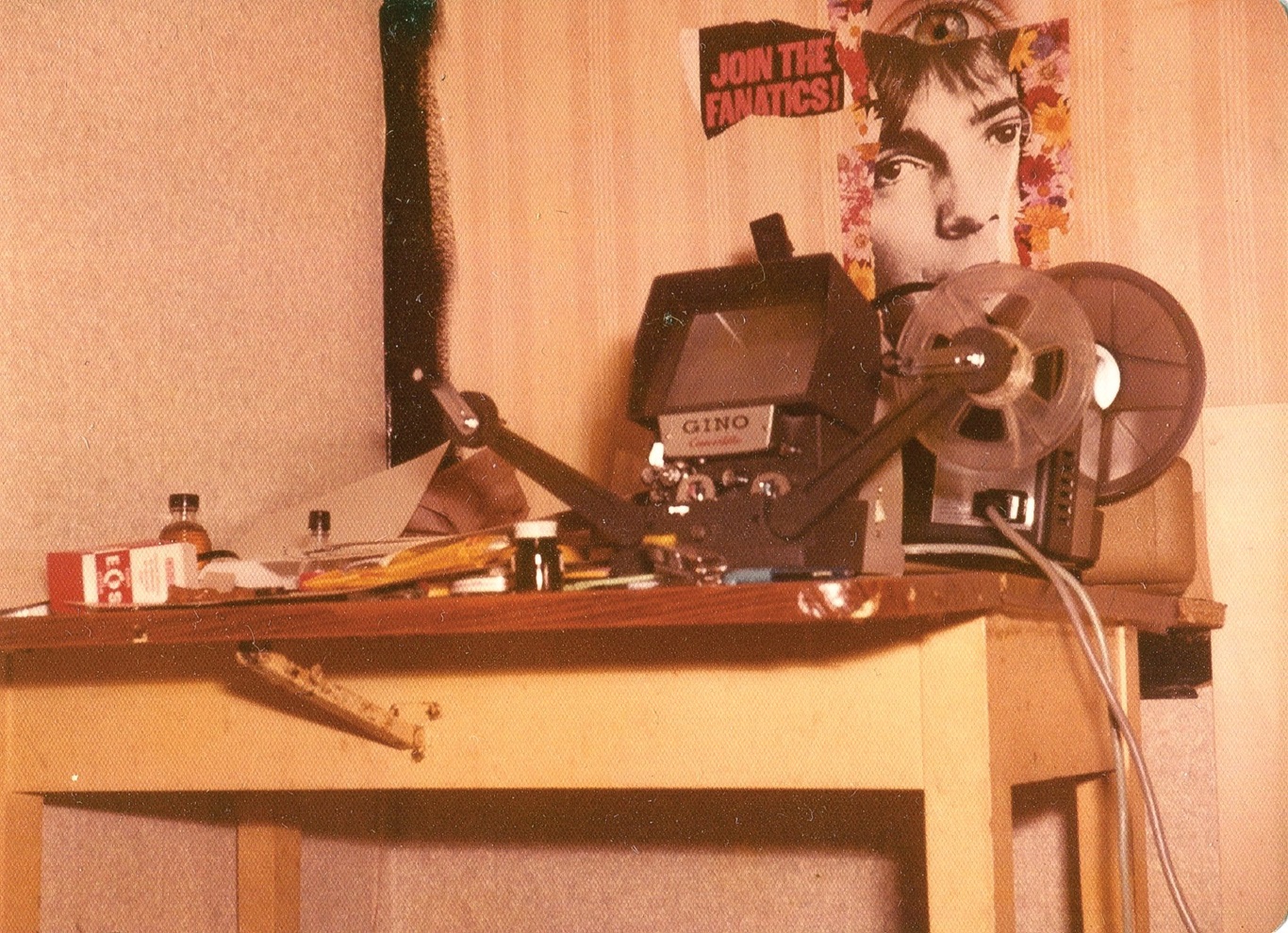

There are other ways it could be read, but we’ll leave them for now. Because, his antipathy to biography is not Robertson’s only qualification. The Boston, Massachusetts-based professor of media studies grew up in Dunedin where he had his "mind blown" in 1981 after hearing The Clean’s song Anything Could Happen on a radio station countdown — a song recorded on Knox’s storied 4-track reel-to-reel tape machine. More on that later.

As a result of that aural awakening, Robertson spent the rest of the decade buying second-hand Flying Nun vinyl from Roy Colbert’s Stuart St Records Records shop, Knox band Tall Dwarfs a favourite, and, while at the University of Otago, wrote his history honours long essay on the Dunedin Sound — interviewing Knox at his Hakanoa St home in Grey Lynn, Auckland. He was also a contributor to New Zealand music mag Rip It Up back in the day and even published his own fanzine, Side On, in the ’80s.

Still, his new biography, Chris Knox: Not Given Lightly, is a genuine departure from Robertson’s more recent output, a book on the history of the passport and another on filing cabinets.

"So, I guess the challenge was to take an interesting thing, of course, an interesting person, and try to keep that interesting."

The ambition was a little grander than that though. One of the big motivating factors, he says, was to produce a record of Knox and the creative communities of which he's part.

"I wanted that biography to exist literally on the same shelf as biographies of Frank Sargeson, Janet Frame, Colin McCahon, Maurice Gee, Maurice Shadbolt, right? So, I wanted to write, in that sense, a serious biography. Because I believe that Chris Knox and, again, the creative communities he's part of, are as important to New Zealand culture as those more venerated writers and poets and artists."

So, it’s a legit fanboy project. But Robertson has a ally in legitimacy in his subject, who went from questionably hygienic, self-absorbed, jandal-wearing Dunedin hippie in the mid ’70s, via punk rock, to recipient of the Commemoration Medal — a royal honour — in 1990. In the event, he turned the medal down, leaving Ray Columbus as its only awardee from the world of rock’n roll. Or, as Robertson writes in his biography: "Chris Knox had begun the 1980s smashing watermelons and smearing their flesh and juice over himself in front of 20,000 people [at Sweetwaters] ... ", and ended the decade with the offer of a gong.

How such a thing could have transpired clearly requires some explanation, and Robertson takes all of 272 pages to get to that point in the story — before finishing up at page 389, not counting the notes, timeline, select discography and index. There are lots of pictures.

Naturally, the telling careers through the sex, drugs and rock’n roll, The Enemy’s formation and first gig at Dunedin’s Beneficiaries Hall in 1977, Toy Love’s assaults on the music charts and Australian adventures, and on to Knox’s experiments in bedroom recording that helped propel the South’s jangle pop to something approaching international fame and made him a hero to indie musicians the world over.

A good bit of which is familiar history — though Prof Robertson’s assiduous research for the book provides endlessly entertaining detail (Include the story about Toy Love drummer Mike Dooley’s indignation at being served an underwhelming steak sandwich in New Plymouth or leave it out? Leave it in.) — but in getting to the story of one of Grey Lynn’s best know residents, Robertson first travels to Invercargill, where Knox was born in 1952. And it turns out that Invercargill was at least as formative as Johnny Rotten — even if Knox himself has been more profusive about the latter.

However, he reacted to his predicament with the same creativity that has marked the decades since.

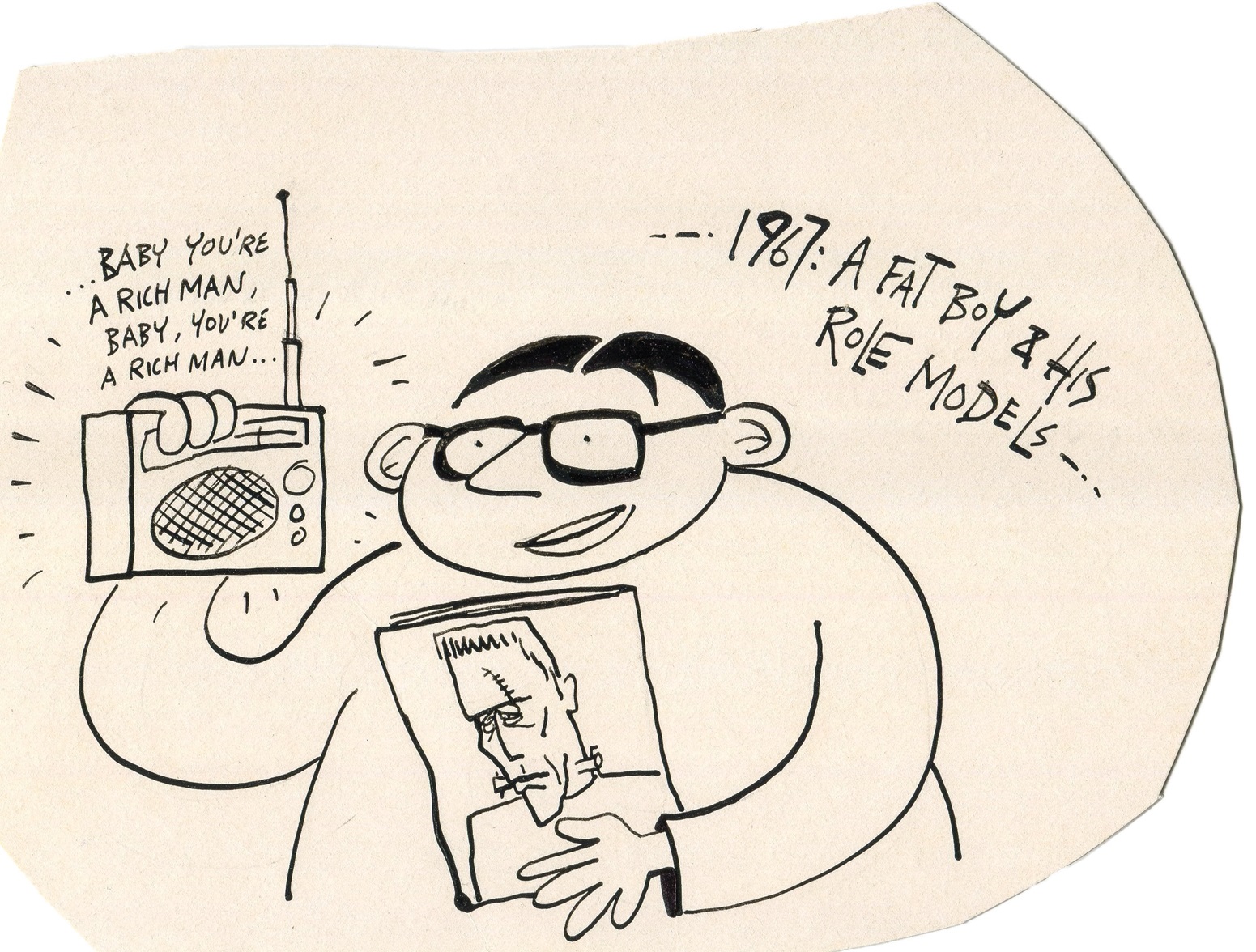

"In his childhood in the 1960s in Invercargill, he created an aesthetic, he came to an understanding of culture and creativity and performance and expression that, without doubt, he maintained through the rest of his life," Robertson says.

As far from the world as he was then, he worked hard from an early age to access the music, film and comics that were important to him then, and remained so — from Mickey Mouse and Hammer Horrors to the Beatles, especially the Beatles.

"I think in the midst of being unhappy in Invercargill, the Beatles come along, you know, and they completely changed his life. It changed his life in terms of an understanding of creativity."

The avant garde musique concrete of "White Album" song Revolution 9 bowled him over.

"The Beatles were the most accessible sign of social change, of ideas of liberation," Robertson writes.

That said, had anyone been asked back then, or even in Knox’s early days in Dunedin, what he might have become known for, it’s unlikely they’d have nominated music, Robertson observes. Film or cartooning would have been regarded a better bet.

They’d have been half right, as he achieved notoriety in both of those fields too.

It’s a testament to Robertson’s dedication to his subject that he’s drawn such a clear outline of those early years. Because, as a biographer, he was faced with the daunting challenge of writing a book about someone who was still around, but wasn’t in a position to be interviewed.

Knox suffered a debilitating stroke in 2009, just months after Robertson had first talked to him about the prospect of a biography, and received his blessing.

It wasn’t until 2016 that Robertson began the project in earnest, but while Knox had been able to resume some of his creative endeavours, he wasn’t going to be an interview subject as such.

"But what Chris did was, he contributed in a really important way by having a house full of basically every interview that he'd ever given, you know, that he'd collected and record labels had sent to him and so forth, and having this amazing collection of these things, of these interviews in which he is incredibly ... it's pretty honest, right?"

There were journals too and his own output as a published writer, including articles for The Listener and Real Groove magazine.

"He might've been writing opinion columns or film review columns, but they were intensely autobiographical, right? And quite honest and upfront."

What it all confirmed for Robertson, if any confirmation was needed, was that Knox was an original — unique in the New Zealand setting, within the world of Flying Nun and beyond our shores.

Robertson’s book also confirms the critical role Dunedin played in Knox’s development. And not just because that’s where he was living when the Sex Pistols released Anarchy in the UK. Though that was undoubtedly important. As Knox wrote himself, recounted in the biography, "Johnny Rotten came along and saved all our lives by showing there were other people around who were as bored shitless as we were and had a way of venting that".

"I think Dunedin, in part because of the university, brought together a lot of people, including Chris," Robertson says, "that could help the slow and gradual development of his different creative outlets. Encourage and support him in different ways."

It meant, for example, when The Damned drop their first single, Neat Neat Neat, in 1977, he could be hanging out at a record store — "wearing a moth-eaten op-shop fur coat held together in places by tape over what seemed to be a postie’s uniform" — and have a couple of serendipitous encounters with The Enemy’s two other founding members, Alec Bathgate and Mike Dooley, who had turned up to buy it.

Knox had long been a voracious consumer of all sorts of music, but up to this point he was in the audience.

"Music was not the outlet, right," Robertson says. "At that point he was making a lot of short films, he was drawing, that was his creative outlet. Then suddenly, there was this moment when, it was like, ‘oh, you only have to be that good to be in a band’."

Here was an alternative approach to the pedestrian imitation of Dunedin’s boring covers bands, which he regarded with disdain.

Punk allowed music to leapfrog all other concerns.

Knox’s early bands The Enemy and Toy Love soon found first notoriety then fame, but it was their demise and what Knox did with the cultural capital they afforded him that was important.

We now approach the mythology surrounding the role Knox’s 4-track played in the development of Flying Nun, independent music and home recording internationally — and the allied impact his DIY music videos had on others.

As Robertson writes, they were shocked by their ability to record sounds they’d struggled to nail in the flash Sydney studio Toy Love had used the year before.

Recording at home gave them complete artistic control. So, those first lounge recordings included the totemic Nothing’s Going to Happen featuring a child’s rattle and a wine glass.

Armed with the technology and the associated know how, Knox’s 4-track was soon used to record The Clean’s Boodle Boodle Boodle EP, and not long after the Dunedin Double EP, featuring The Stones, The Verlaines, Sneaky Feelings and The Chills. By which stage, the Dunedin Sound was pretty much scratched into history and Flying Nun was airborne.

Part of the dynamic at play was Knox employing his notoriety to open the door for others, Robertson says — while simultaneously warning newcomers against the pitfalls of the music industry. His Australian Toy Love experience had left him thoroughly convinced "industry" and creativity were mutually incompatible.

"Because of Toy Love, by the 1980s he was famous, he was a known person, right? So, Chris Knox literally gives you permission by saying, here, here's my 4-track, go record yourself."

In a similar way, he was able to launch one of New Zealand's first alternative comics, Jesus on a Stick, in 1984.

He was a force of nature, and others were caught up in his wake in some really positive ways, Robertson says.

Knox had long been an advocate of the great song, and Robertson argues this is another way to approach the Dunedin Sound phenomenon and his influence on it. The Enemy and Toy Love had them, the likes of Pull Down the Shades and Squeeze.

As far as Knox was concerned, most pop music was well recorded collections of sounds and noises, devoid of substance.

"He’s just interested in using what technology is available to capture the song, and to capture the song as it’s performed by the person who wrote it, by the musicians."

Which brings us back to the idea of honesty, something Knox has often talked about, Robertson says.

"Diving deep and basically reading every interview that Chris ever gave, you see that there is this really consistent take on honesty as being absolutely central to what it means to be a human being."

This was, according to Knox, about the only thing he kept from his Invercargill religious upbringing.

It came with a warning though, as his honesty could often be egotistically and bluntly confronting — to friends and others alike.

Robertson records a moment in 1979 when Dudes frontman Dave Dobbyn caught up with Knox at a gig, between sets, to tell him how much he liked Toy Love.

"Knox told Dobbyn how awful Th’ Dudes were," Robertson writes.

As a function of all this creative outpouring, Knox’s profile continued to rise on the way to the offer of that Commemoration Medal, having become, along the way, the media’s go-to guy for an alternative take on the issues of the day and having further confirmed his pop sensibilities with the ear-worm single Not Given Lightly.

It’s a story that thunders along on a tide of chaotic internal logic. Though one element of Knox’s narrative remained tantilisingly beyond the professor’s efforts to nail down. The idea of nothing.

Back in his pre-punk Dunedin days Knox set off up the country, with others, on an acid-fuelled roadie dubbed the "search for nothing", which "catalysed Knox’s interest in the idea of ‘nothing"’.

"Among other things, [nothing] would eventually become the name of a van, a song and a band," Robertson writes.

The idea of nothing is clearly really important to Knox, he says, carrying both positive and negative elements — the lyric to Nothing's Gonna Happen being a case in point.

At the start of the song, the prospect that nothing is going to happen is a problem, but by the song’s close, it’s something nearer to a comfort.

"So, he was clearly very fascinated with this idea ... that nothing provides a way to experience the world or a framework through which we can think about the world.

"Unfortunately, he was never asked about it in interviews, and so that's one of the few gaps, if you like, in the book."