Picture this: an airport at the end of Otago Harbour, a tunnel under Mt Cargill and aerial walkways linking buildings on the University of Otago campus.

That’s how Dunedin would have looked if epic plans from the past had become reality.

Instead, architects’ offices and old newspapers are full of concepts that never made it off the drawing board. Sunk by shifting fads and changing fortunes, public opposition and political power struggles, these grand schemes have largely been forgotten.

Many of the most ambitious date to the second half of the 19th century, when Dunedin was New Zealand’s main industrial and commercial centre.

But even before that, locals were thinking big.

One example: a plan surveyor Charles Kettle produced in 1846 shows he briefly considered Bell Hill, which overlooked central Dunedin, a suitable site for a castle. Worried about potential conflict in the colony, the New Zealand Company had instructed him to include fortifications in the town plan.

It wasn’t until building materials began piling up on the reserve that the local — predominantly Presbyterian — community became aware of the project and a new site was found in the northwestern quadrant.

Many years later, in 1968, the city planning department suggested closure of the main road through the Octagon.

This idea was later taken up by the Otago branch of the New Zealand Institute of Architects, whose proposal would have moved the central carriageway underground.

For a scheme that was both ambitious and visionary, it would be hard to beat the one promoted by young Dunedin businessman and railway enthusiast Ernie Webber in 1931.

Webber planned to form a company and raise several million pounds of capital in London for a wide-ranging tourism operation that would "exploit the whole of the provincial district of Southland lying south of Milford Sound and eastward of a line from Milford Sound to Lake Wakatipu".

The scheme included steamer and motor boat services, light rail routes and hotels.

Even when projects did come to fruition, a lack of funds meant some were not completed as intended.

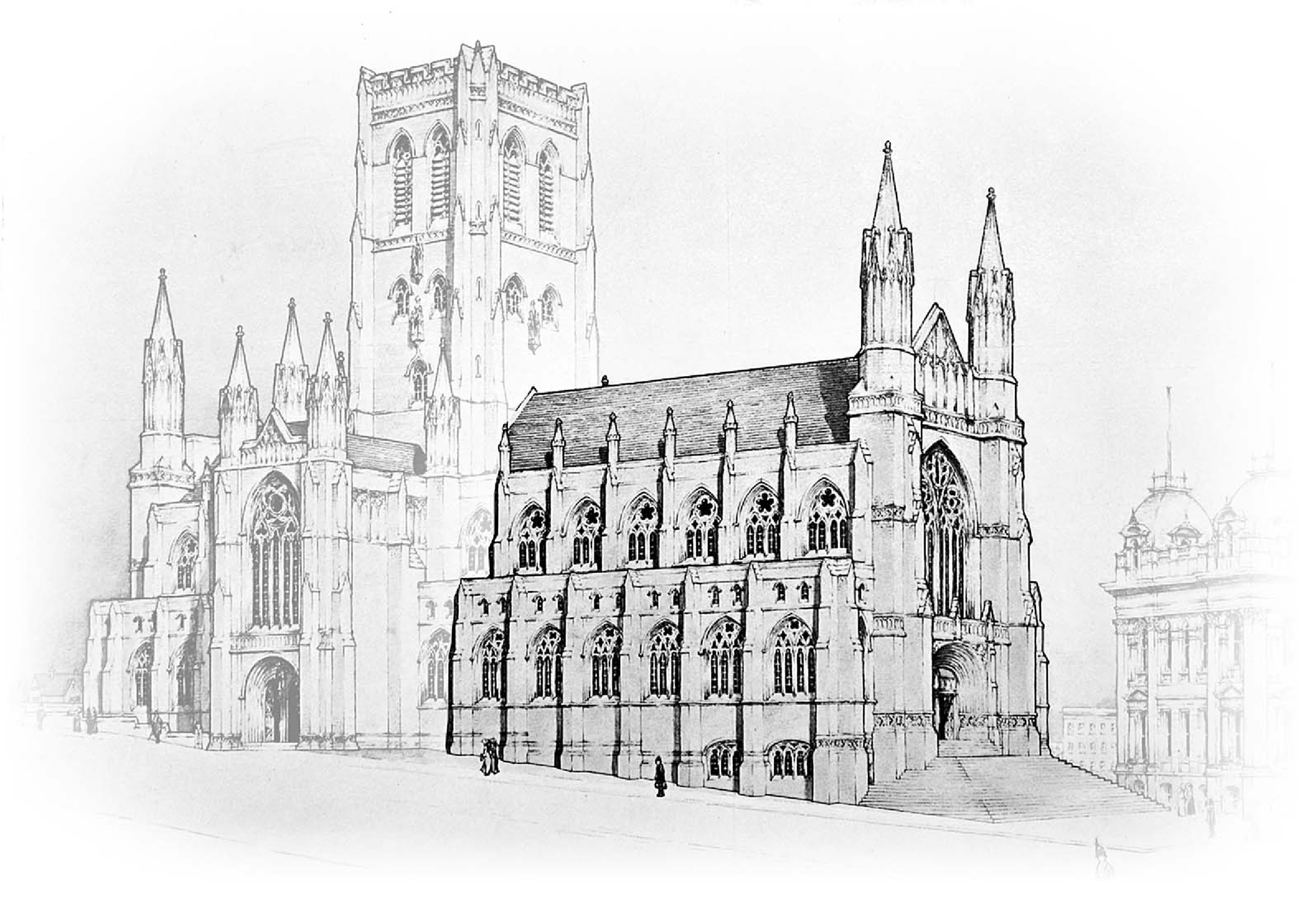

The original plan for St Joseph’s Cathedral envisaged it twice as long as it is now, with a 60m- spire, while St Paul’s Cathedral was to have been built in the shape of a cross, with a tower at its centre, but only the nave and chancel were ever finished.

Meanwhile, Dunedin’s municipal chambers would look very different today had the winning entry in an 1877 design competition been used.

Architect Thomas Cameron entered an imposing classical design with rounded arch windows and a corner tower.

After initially accepting his plan, the town hall committee became concerned about the cost and instead opted for the design by runner-up R. A. Lawson.

In hindsight, it’s fortunate that some developments didn’t go ahead.

In the 1960s, the Dunedin City Council works department proposed knocking down the municipal chambers to make way for a new civic complex.

In the 1950s, the University of Otago clock tower and professorial houses were under threat of demolition and before it was bought by the city council, there were even fears the Dunedin railway station would be levelled.

Among the many other schemes that never eventuated: an 1880s plan to bring large vessels to the Dunedin wharves by cutting a ship canal from the Tomahawk side of Lawyers Head through to Rattray St; a 1960s proposal by the city planning department to create a "reconstructed early settlement" with replica cottages at Jubilee Park; and a controversial plan in 2006 to add a 60m-high viewing tower to Toitū Otago Settlers Museum.

In the 1990s, there were calls to turn Cumberland St into a two-way tunnel under the University of Otago campus and several huge shopping malls were being considered, including one at Fairfield with 200 shops and 3000 carparks.

However, the city’s proposed district plan limited large-scale retailing to the central city.

There have also been big plans to redevelop Dunedin’s waterfront.

In 2017, architect Damien van Brandenburg unveiled a 30-year vision for the Steamer Basin, which was widely praised but has not yet progressed any further.

The concept included a public aquarium, a low-rise hotel and a clam shell-shaped cultural centre.

Meanwhile, a scheme from the council and Port Otago subsidiary Chalmers Properties 20 years ago included areas for apartments, tree-lined boulevards and even an "Amsterdam-style" canal that could be frozen in winter for skating or curling.

Read on for 10 more local landmarks that were planned but never built.

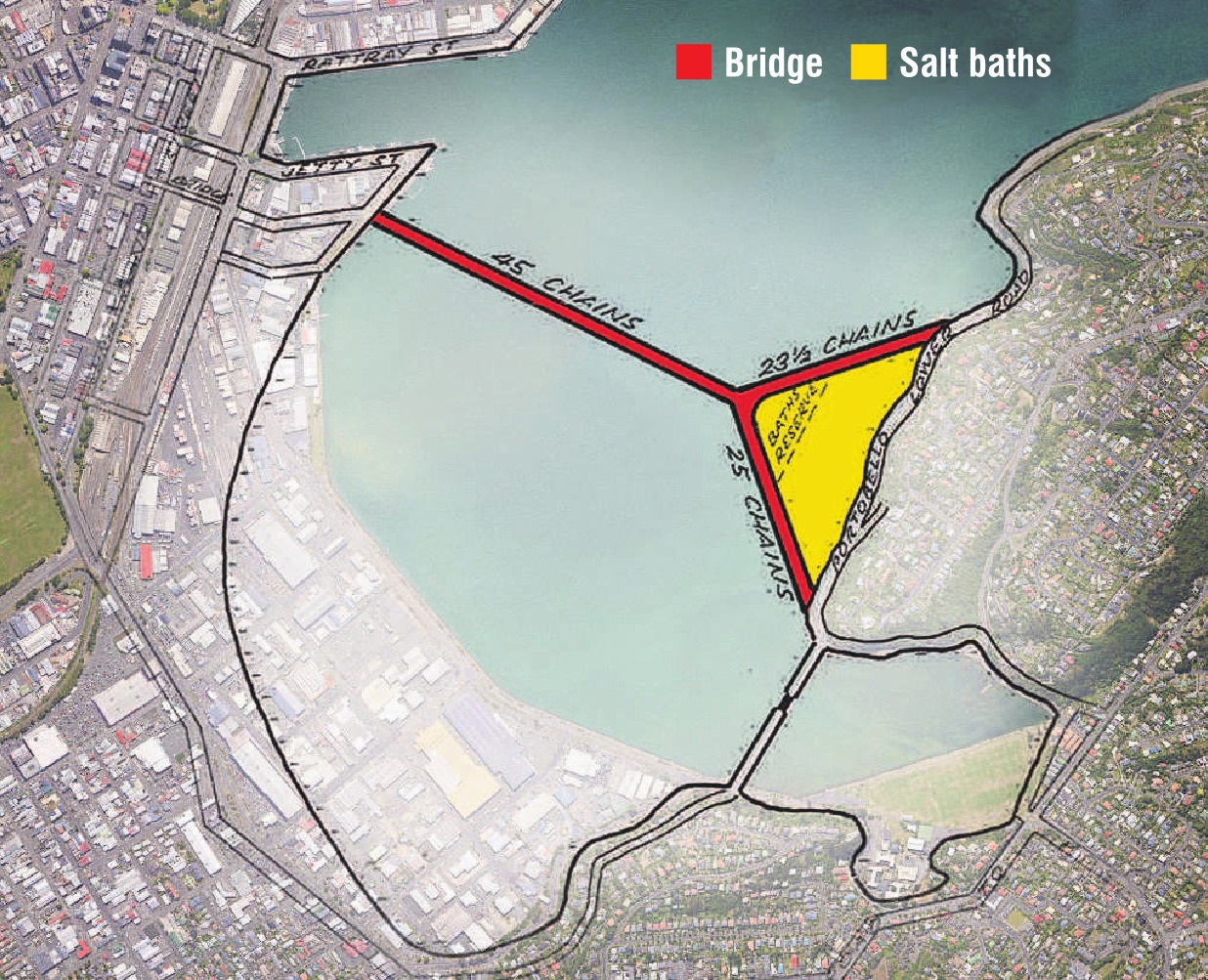

1. THE BRIDGE ACROSS OTAGO HARBOUR

More than 70 years before Auckland built its harbour bridge, there were plans for one across Otago Harbour.

The structure would have started somewhere around Jetty St on the city side, and on the far side would have had two branches leading to Vauxhall and Waverley.

If that wasn’t impressive enough, there would be saltwater baths between these two forks.

Promoted by the Peninsula and Portobello Road Boards, the toll bridge ran into opposition from several quarters.

Floated in 1886, the proposal soon sank without trace.

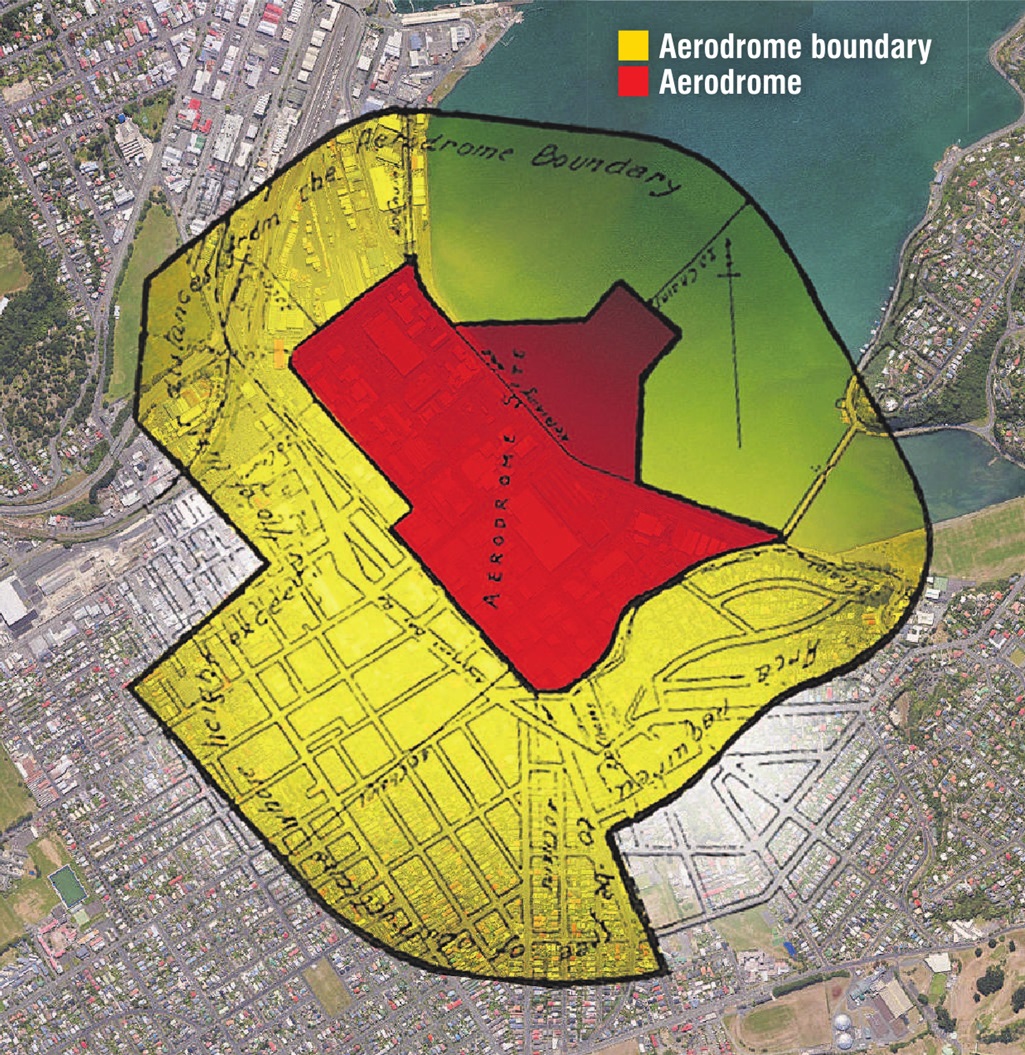

2. THE HARBOUR AIRPORT

Given the size and power of today’s aircraft, it’s probably best this idea didn’t "take off".

For more than 30 years, Dunedin debated whether or not it should build its main airport in the city, on land reclaimed from Otago harbour.

The idea was suggested around 1930 by the Otago Aero Club, which had conducted successful test flights in the area and claimed the distance between the city and Taieri aerodrome discouraged people from going flying.

Some community leaders supported a city airport, predicting planes of the future would not need wings so a small landing area would be sufficient.

Others were concerned about the prevailing winds at the proposed site and the cost of the project.

Writer Jim Sullivan said the runway would have been lengthy enough to accommodate the planes of the time "but before long, it would have been far too short".

In fact, to provide today’s level of service, it would have to extend from Andersons Bay Rd to Forsyth Barr Stadium.

The idea eventually "faded off the radar" and by 1960 it had been overtaken by progress at Momona, Mr Sullivan recorded in his book, Flight Path Dunedin: a history of aviation in Otago.

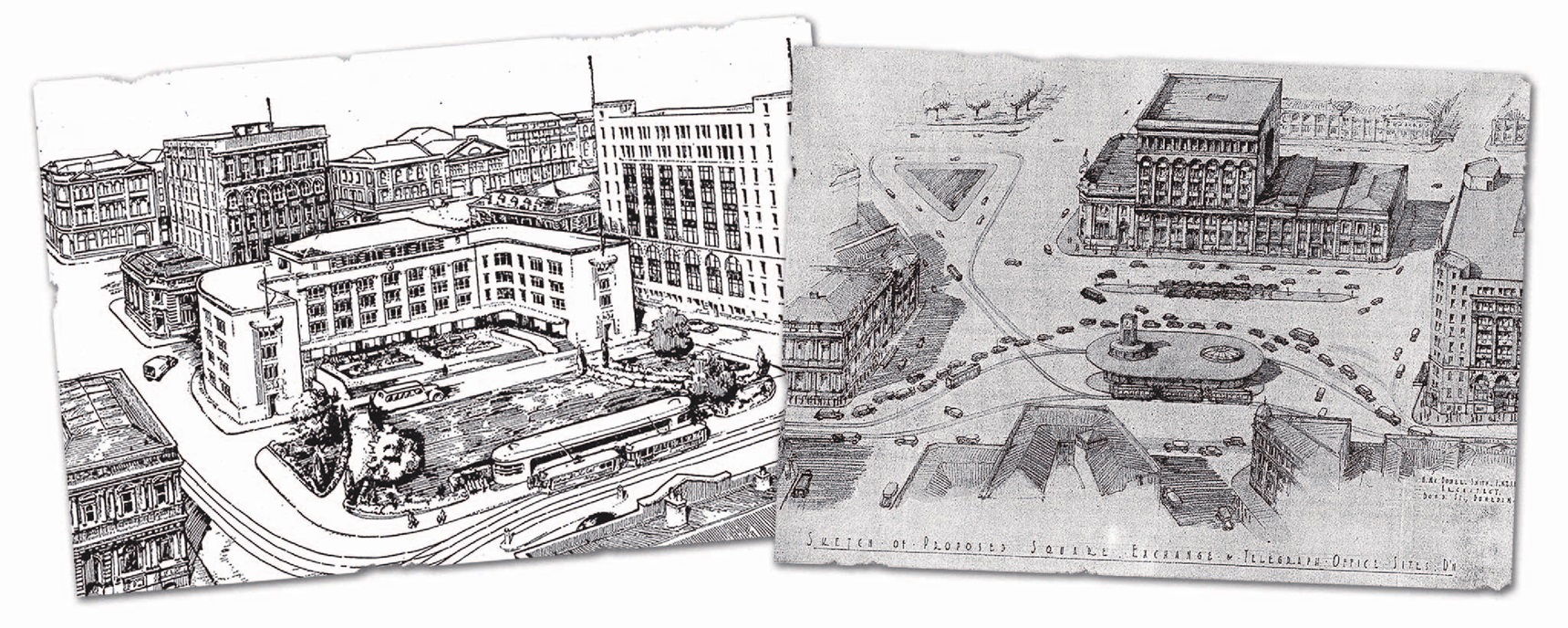

3. THE CIVIC SQUARE

Dozens of projects were suggested to mark a century of European settlement in 1940 and Otago’s centennial in 1948.

These included reclamation of Anderson’s Bay inlet for a swimming pool and stadium, a seaplane base at the head of the harbour and tepid baths on the Market Reserve.

The Otago branch of the Institute of Architects suggested a garden square fronting Princes St.

A new building in place of the Stock Exchange would contain shops, offices, restrooms and a roof-top restaurant.

An earlier scheme promoted by the Otago Expansion League showed tramway services radiating from a central point, subways leading to all sides and a transport hub in the middle.

Both schemes would have meant the removal of Cargill’s monument.

4. THE TUNNEL UNDER THE MOUNTAIN

The main route north of Dunedin rises 369m to the top of the Leith Saddle before descending to Waitati.

Before the Northern Motorway opened in 1957, there was a proposal for a road tunnel under Mt Cargill to avoid such a climb and to reduce the likelihood of motorists encountering fog and snow.

While details are sketchy, it’s thought the tunnel would have gone from Sawyer’s Bay to Waitati.

Instead, the new road north crossed Mt Cargill on its inland shoulder.

Dunedin’s southern motorway would also have included a tunnel if plans in the late 1960s had become reality.

Traffic would have travelled under Lookout Point, emerging at Caversham.

Another idea to be parked was a 1970s proposal for a direct link between Kaikorai Valley and the north of Dunedin, enabling north/south traffic to bypass the city entirely.

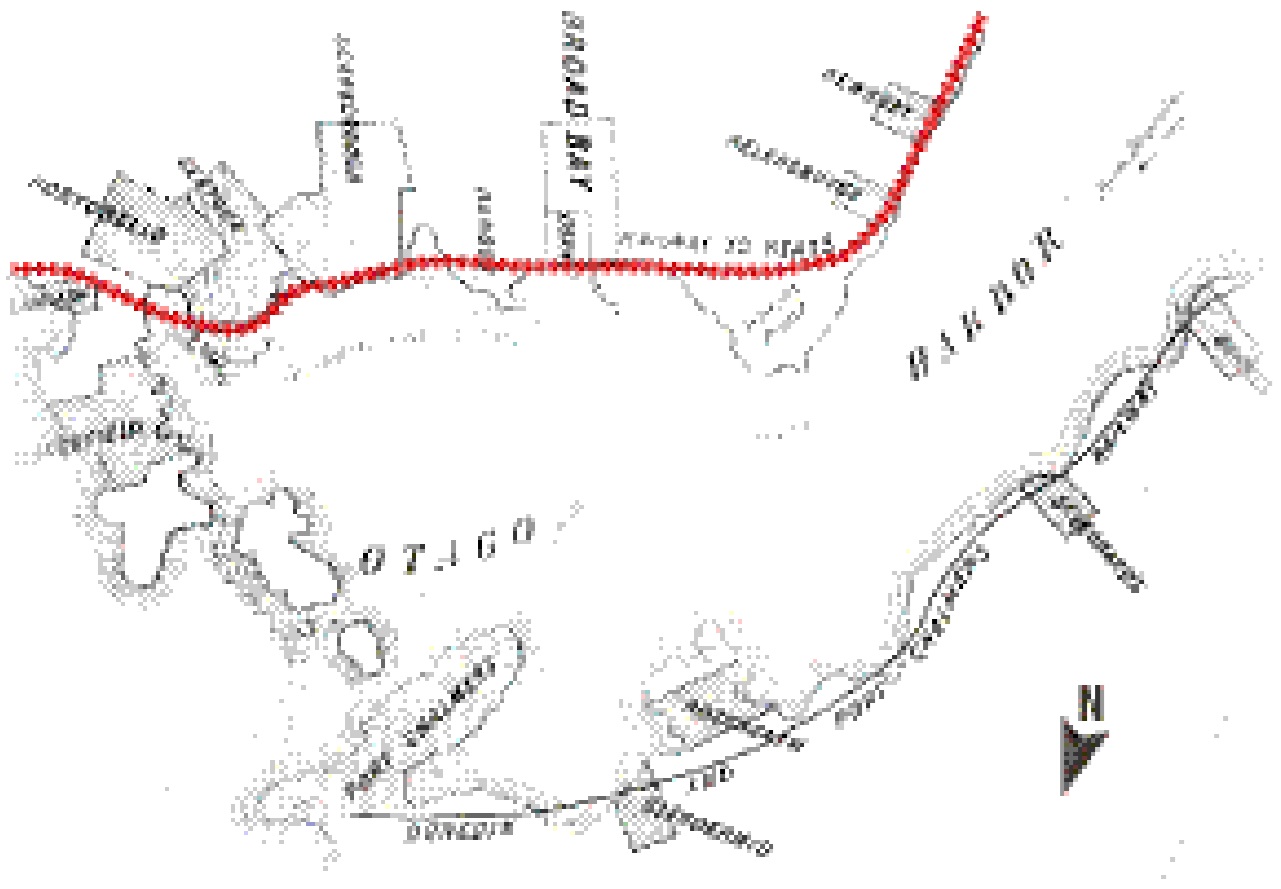

5. THE PENINSULA RAILWAY

In 1874, there were plans to build a railway line from Dunedin to Portobello and the Otago Heads.

Services did start but competition from horse-drawn trams meant Andersons Bay was the end of the line for the Dunedin, Peninsula and Ocean Beach railway.

6. THE HOSPITAL AT PINE HILL

If plans in 1912 had come to fruition, Dunedin would have a hospital in Pine Hill, not in Wakari.

The need for a secondary, or overflow, hospital which would also accommodate people with infectious diseases such as tuberculosis was recognised by the Otago Hospital and Charitable Aid Board around 1910.

After investigating many potential sites, the board bought 9ha of land at Pine Hill "just above Dalmore", had architects draw up plans, planted shelter trees and paid for an extension of the city water supply.

But not everyone was in favour of the location.

One board member described it as "bleak and uncomfortable".

Architects said obtaining a northerly aspect would be difficult and the ground formation would make building expensive.

The site was also considered too small to cater for future needs.

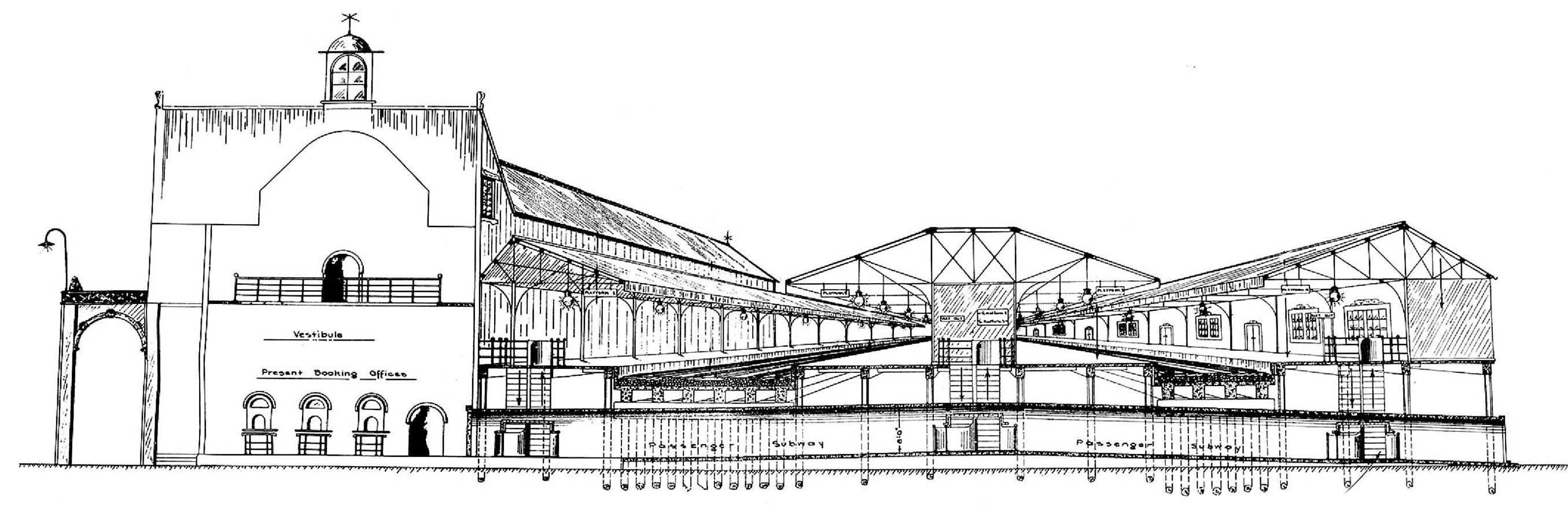

7. THE ELEVATED RAILWAY

In 1920, the Otago Harbour Board owned "hundreds of acres" of land on the foreshore side of the railway line and the only access to it, particularly at the north end, was via Rattray St.

This road was often blocked by trains running over the crossing.

Frederick, Hanover, Rattray and Jetty Sts would all have overhead rail bridges while the railway station would have raised platforms, subways for passengers and elevators for luggage.

The plan can be seen in the McNab room of the Dunedin Public Library.

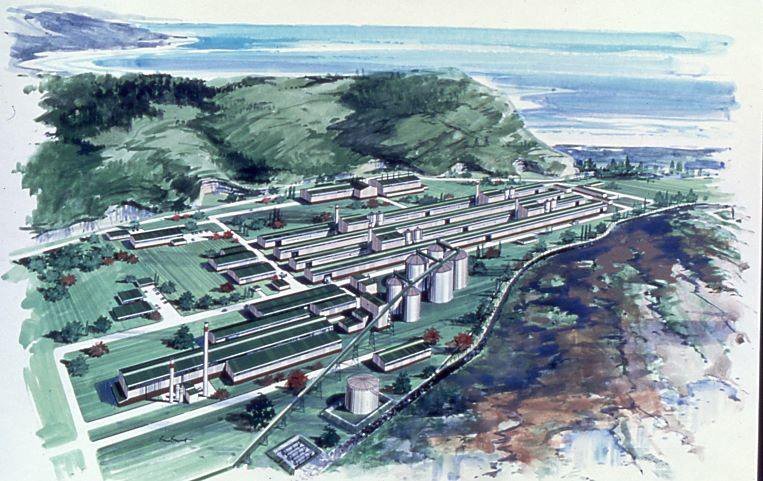

8. THE SMELTER AT ARAMOANA

The villages of Aramoana and Te Ngaru and an ecologically important wetland would all have been destroyed had this proposal during the National government’s "Think Big" era gone ahead.

The government endorsed the consortium but local residents founded the Independent State of Aramoana, established a "border post", printed passports and postage stamps, and set about using the resultant publicity to build a national grassroots campaign in opposition to the project.

The scheme was finally abandoned in 1981 due to a combination of factors. These included public opposition, declining aluminium prices, the withdrawal of one of the consortium partners and the remaining companies being unable to secure additional capital.

9. AERIAL WALKWAYS ON CAMPUS

"Higher learning" is one thing but if plans in the mid 1960s had materialised, the University of Otago campus would feature pedestrian overpasses.

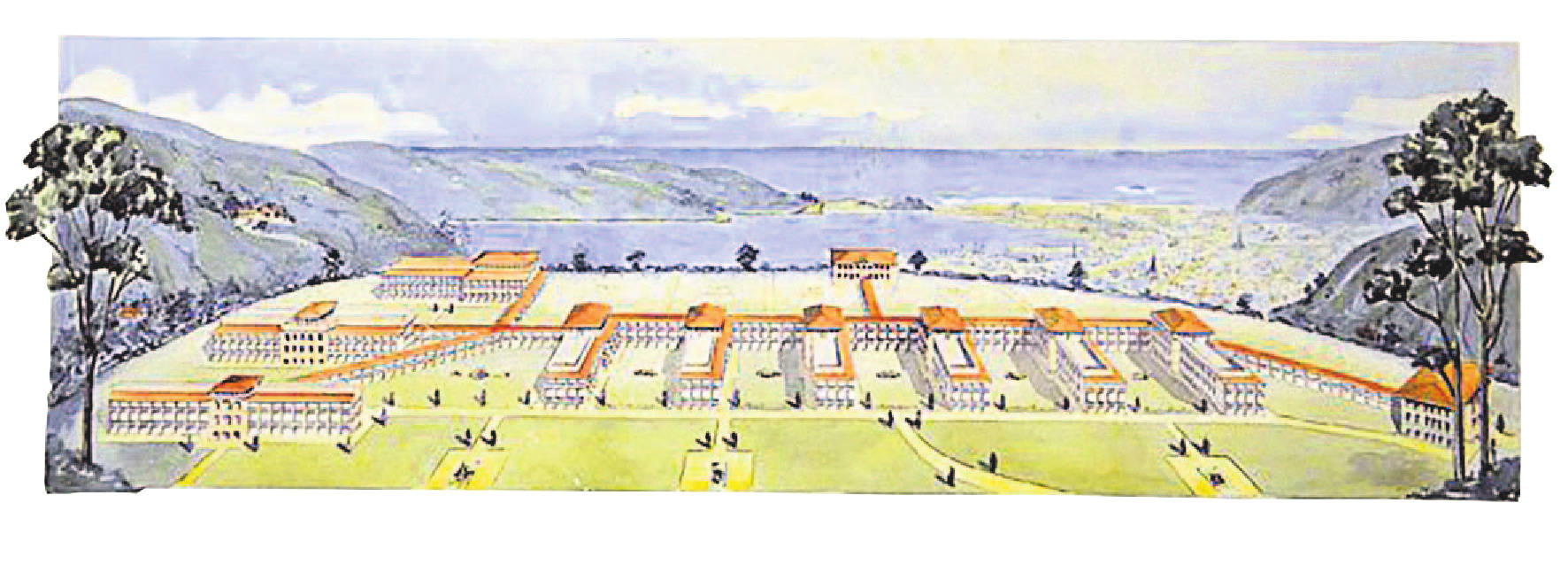

The 1960s and 1970s were a period of expansion on campus and at the centre of this was a plan produced by assistant government architect John Blake-Kelly.

Some buildings had large first-floor circulation spaces included in them to allow for these aerial routes but concern arose over implications of such a complex and expensive circulation system.

Instead, the university advocated for a traffic-free campus and some of the area’s busy streets were closed to vehicles.

10. THE WATERFRONT HOTEL

Dunedin has seen several proposals for luxury hotels come and go, including one for a 17-storey hotel on the Filleul St carpark opposite the town hall.

The 96m-high glass tower, including hotel rooms and apartments, would easily have been the city’s tallest building.

A planning application by Betterways Advisory Ltd attracted more than 500 submissions, all but 50 of them opposed to the building — particularly its height and the impact on its surroundings.

The company failed to obtain resource consent and later scrapped the project.

Additional information provided by Hocken Collections archivist David Murray.