Phil Ker, the man at the helm of Otago Polytechnic for the past 13 years, once harboured dreams of becoming a carpenter. From a young age, he'd build things. He still does.

Currently, he's working on a 10sq m sleepout. Requiring no council consent given its size, the project could be regarded as a foil to all the other sleeves-rolled-up work in which the institution's chief executive is involved.

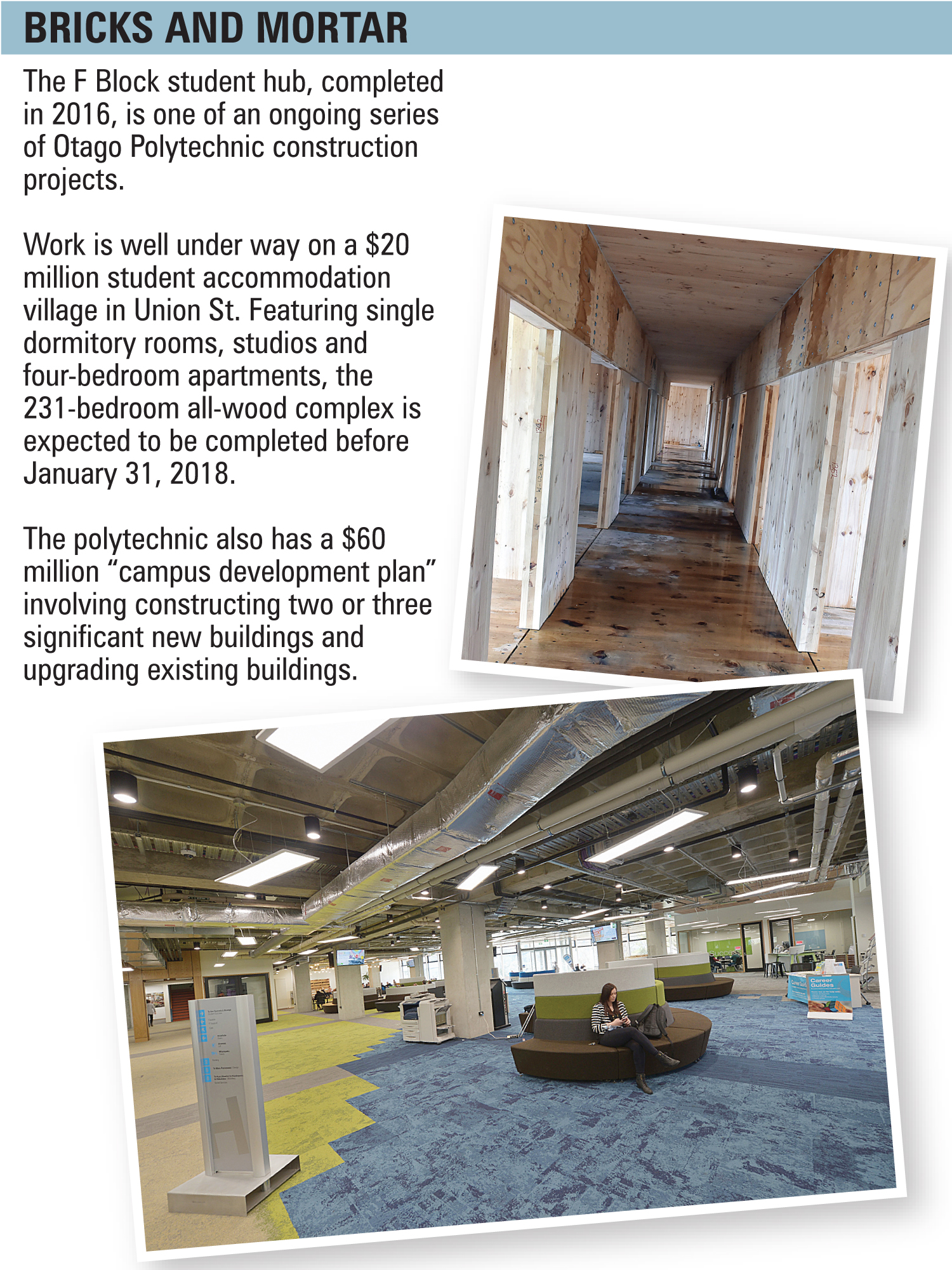

This includes Otago Polytechnic's new $20 million student accommodation village on Dunedin's Union St where, amid the clank, thwack and buzz emanating from the construction site, a couple of sounds manage to rise above the rest on a weekday morning.

One is the beep, beep, beep of a machine in reverse, in contrast to all the forward momentum on display; the other is the scraping of a digger's teeth on concrete, prompting a shudder not unlike the response to nails on a blackboard.

Not that many, if any, of the students destined to fill the 231-bedroom complex would make such a connection. In a world of digital devices, the only chalk to be found in these parts is on the footpath up the road, where a series of scrawled messages offer directions to a public talk by a former occupational therapy student.

Around the corner, beyond the Forth St entrance of the polytechnic's Hub, Ker is discussing business with a couple of colleagues. Nearby, a woman in a banana costume encourages people to hop on a static bike to which is affixed a blender; a few metres away, an enormous globe sculpture crafted out of domestic appliances demands attention amid an atmosphere of quiet chatter and occasional laughter. Ker pops across to say hello, acknowledging an earlier interview in which he disclosed much (but not all) of what makes him tick, and what has helped turn around the fortunes of an institution that, arguably, has sat in the shadow of its larger neighbour, the University of Otago.

Ker shelved his carpentry plans in seventh form, deciding instead to head into tertiary education, where he has been ever since, in one role or another. Still, he has an eye for both the broad plan and the finer details.

Expected to be completed in early 2018, that all-wood accommodation complex rising high above the hockey turfs at Logan Park is part of an ongoing series of Otago Polytechnic construction projects.

These include F Block's Hub, the institution's vibrant centrepiece, completed in 2016; and a $60 million ''campus development plan'' involving constructing two or three significant new buildings and upgrading existing buildings.

Much of this has to do with Otago Polytechnic positioning itself not as a regional tertiary education provider, but one that competes both on a national and international stage. An examination of its 2017 roll bears this out: of its 3995 equivalent full-time students (an increase of 2.3% on last year), 567 are international students. Significantly, that's an 44% increase on 2016.And more are coming. Agreements with Chinese and Japanese institutions will result in about 250 foreign students studying at the polytechnic in both 2019 and 2020.

Hence all this construction noise.

''If we are to be nationally and internationally competitive, then our facilities have to be fit for purpose,'' Ker says.

''Learners' expectations have changed. No one wants to spend hours listening to lecturers. The curriculum of the future involves experiential education, students being active. We need studios and workshops, collaborative learning spaces.''

Ker concedes criticism has been levelled, ''that we have abandoned our roots'', alluding to the traditional notion that polytechnics service the educational needs of those both in their cities and wider regions.

In fact, nowadays, just over half of Otago Polytechnic's students hail from outside the province. Several years ago, that figure hovered around 25%.

''We made a strategic decision to be a national polytechnic, that we would attract people from all around New Zealand as well as internationally. International numbers have only really been a phenomenon for us in the past four years or so,'' Ker explains.

''When we started implementing that we had the advantage of leveraging off the University of Otago, but in my time here we have doubled the proportion of students who come from outside the province.''

How has Otago Polytechnic done this? Well, increasing the number and depth of higher-level programmes has helped. It now offers more than 40 bachelor and/or postgraduate programmes. Building on traditional strengths such as trades training, nursing, midwifery, occupational therapy and business courses, the institution this year launched a Bachelor of Architectural Studies, for which a second class has been added (there is also a waiting list). Other recent courses introduced in recent years include a Postgraduate Diploma in Design, a Master of Design, a Master of Professional Practice, and a Bachelor of Culinary Arts. A new Bachelor of Construction should be available from 2019, subject to final approval.

In September last year, Otago Polytechnic launched a joint degree in Mechanical Design Manufacturing and Automation in partnership with Dalian Ocean University in China's Liaoning Province. Three years of the four-year degree will be completed in China, Otago lecturers travelling there for up to six weeks at a time to deliver part of the programme. The students will then travel to Dunedin to articulate to the Bachelor of Engineering Technology (Mechanical) for their final year at Otago Polytechnic. The Chinese government has approved an annual intake of 120 students.

It's a matter of simple analysis, Ker says. Students seeking degrees are typically committed to at least three years study, so they are prepared to move.''

In contrast, certificate and diploma students tend not to move to study.

''The volume of teaching we do for the trades is pretty much the same today as it was 10 years ago. We still do all that; we haven't lost our roots. But we are a stronger organisation because we have gone nationwide.''

However, as Ker notes, the strategy is also a potential weakness: the student who chooses to move to study at Otago Polytechnic is, by definition, one mobile enough to study somewhere else.

''That's why I argue so strongly that we have to offer top service, top programmes, top facilities. We have to be attractive.''But we put just as much energy into our students.''

A report by the Tertiary Education Commission last year bears this out: it found Otago Polytechnic had the highest percentage of students successfully completing qualifications (90%) and courses (84%) in 2015, compared to 17 of New Zealand's other Institutes of Technology and Polytechnics.

The TEC report also noted Otago Polytechnic was second in the country for ''students retained in study'' (76%) and fourth for ''student progression to higher level study'' (44%). And Otago Polytechnic's 2015 annual report stated 98% of its graduates were in work or further study.

''I think we are heading towards a strong institution,'' Ker says.

''There are three essential elements to this: we have to be financially strong over the long term; our quality, our educational performance - the essence of our reputation - has to be top-notch; and, lastly, our work environment needs to be good, not only in order to attract the very best, but to allow people to perform to their best.''

"Right now, we are in a really good space."

IT wasn't always this rosy.

The building project involved A Block (the trades building) and H Block. These were upgrades that were not properly scoped and therefore had big cost over-runs - over $2 million, if I recall correctly. The net effect was that all reserves were wiped out.

''... When I arrived the budget was for a very small surplus. However, there was an overdependence on low-level community computing programmes - about 20% of all enrolments - and these had no student fee attached, so were not that successful financially.''

Soon after Ker arrived, the Government decided to stop funding the computer programmes, which created further pressure.

''Around 54 positions had been identified for redundancy,'' Ker recalls over a late-afternoon coffee at an Octagon cafe.

''That's a pretty major recovery exercise and tells you how significant the financial problems were. Of course, that meant very low morale.''

About a fortnight after being offered the Otago job, Kerr received another call from a careers recruiter. Another job was tabled, ''for one of the highest performing polytechs in the country''.

Kerr declined. He was more interested in the challenge, of ''taking something that was broken and working on it''.

Thus began a new chapter in the sector for Ker, for whom education is ''in the blood''.

''My mother was a teacher, and I have a sister who was a teacher before me, so ... I chose to go down that pathway.''

Born in Waiuku, South Auckland, raised in Pukekohe, Ker completed a bachelor of commerce degree at the University of Auckland in 1973 and, concurrently, a teaching diploma at the Auckland College of Education.

He has spent most of his working life in Auckland, apart from three years in Wellington in the early 1990s, when he was president of the Association of Staff in Tertiary Education (forerunner to the Tertiary Education Union).

Having also worked for the Auckland Institute of Technology then the Auckland University of Technology (when the institute was granted university status in 2000), Ker's experience is broad.

It ranges from the academic (teaching economics, accounting and management), to the strategic (curriculum development and assessment, to responsibility for facilities, student services, human resources, and ''equity development''). He was also a key contributor to the establishment of the New Zealand Diploma in Business, a major reform of business education in the late '80s.

At this juncture, there is a catchphrase of Ker's that demands repeating. He has said it before in interviews and, as he reflects, to various members of his staff. It goes: ''It is often far easier to get forgiveness than permission.

''The words are recited back to Ker, who laughs, briefly, before becoming serious as he details the process of hauling Otago Polytechnic out of that rather large hole.

''My first initiative, in 2004, was to introduce a work environment survey. I pulled together a team of managers across academic and general staff. There were about 20 people on the team and the union was represented.

''I explained that the only way for anything to develop was by knowing what wasn't working. The survey ended up including about 70 aspects of the workplace environment. It was about staff satisfaction with the job, decision-making, leadership, communication, strategy, staff wellbeing ...''

At the time people asked him why he'd bother when staff morale was at a low, that he would be inviting a broadside of negativity.

Of those staff surveyed, 80% responded. And, yes, much of it was highly negative, Ker reflects.

''But why would I be concerned about that? I was new. I wasn't the cause of the negativity.

''My job is to introduce changes. But nothing is changed overnight. In some cases, you are looking at changing cultures, upskilling, redesigning academic programmes ...

''I was fortunate at AIT/AUT in that it was led by a man, John Hinchcliff, who firmly believed that if you want to be world-class, then you need to get out and see the world.''

So Ker travelled, ''a lot'', looking at other examples around the world. His mentor used to refer to New Zealand being at the bottom of the world. He took it a step further: ''I talked about Dunedin being further down ... next stop Antarctica''.

''I've encouraged a lot of travel. We do financial benchmarking across the sector and Otago Polytechnic spends more than anyone else on travel. I have discussed this with the polytechnic's council and I think they agree that expenditure is not going to be cut back.

''It's not change for change's sake. I believe quite passionately that my job is to be a good steward of Otago Polytechnic. To do so, I need to gather round me teams of good people who are outward-looking.''

Hard calls have had to be made, too. A recent shake-up of senior management (three senior managers left, another four had their positions changed) has cost Otago Polytechnic $200,000 in severance payments to date.

The restructuring involved replacing a 12-member senior leadership team with a smaller team, which includes Ker and five deputy chief executives, three of whom were recruited externally.

''We had done really good things, but ... I felt that was a team for an era; it had both a strategy and operational focus and it did get the polytechnic out of the ditch, so to speak.

''However, I thought a smaller team, one more focused on strategy, was needed.

''My intent was that there would be a senior role within the organisation for every single one of that team. But there wasn't a place on the executive for every member; it was a smaller team.

''It was the hardest thing for people to accept, and it was the hardest thing to do. It was the hardest year I've faced in my career, bar none.''

KER used to run marathons. That was until he had a knee replacement five years ago. Dodgy joints aside, his baker's dozen of a tenure at Otago Polytechnic provides alternative proof of an ability to stay the course.

The 65-year-old claims he doesn't really get stressed, that he has good coping skills. He suggests he's more likely to lose his cool mucking up one of his carpentry projects.

Walking helps. Ker covers between 10 and 12km five days a week, his journey to and from work traversing a meditative buffer zone that allows him to contemplate challenges and sort and/or dump them on the way home.

''As a marathon runner, I loved having that time by myself.

''I have tried to replace that with cycling. Long rides put you in the same space, as does kayaking. We have a home right on Lake Dunstan so it's a case of only needing to drag the kayak 30m to the water.''

He has other modes of transport, too. Having owned motorcycles since he was 18, he now has a 2004 Harley-Davidson Dyna Super Glide, which boasts a car-sized engine.

When he's not poring over plans, Ker might bury his nose in a novel. He and his wife, Glenys, are ''crime-thriller fanatics''.

The couple have also managed the delicate act of balancing high-flying careers while raising a family of four. Glenys holds a master of career development degree, as well as qualifications in commerce, management, elite performance and teaching, and has a Dunedin-based business, CareerFit. She has significant experience in teaching at both secondary school and tertiary level, as well as roles in senior management.

When Ker moved to Dunedin in 2004, she remained in her job at AUT for another year.

''I took the kids with me, so that was an interesting first year,'' Ker reflects.

''We still had two living at home at that stage, aged 6 and 7, but I had good support.''

AUT also allowed Glenys to work one day from Dunedin so she commuted weekly. It worked quite well.

''Glenys also works as a facilitator within Otago Polytechnic's Capable NZ programme, which recognises prior learning, enabling students to have previous workplace skills and knowledge formally assessed for formal qualifications.

Of their four children, two daughters live in Auckland and their son (who studied engineering at Otago Polytechnic) is working in London. Their youngest daughter remains in Dunedin.

''She hasn't done any tertiary study but is learning that working on the minimum wage isn't going to give her a great life, so she is contemplating studying,'' Ker says, matter-of-factly.

''I was quite a traditionalist in regards my kids getting an education, but my wife has said they need to do it when they are ready.

''On the subject of moving on, Ker chuckles when the question of his long-term future is put to him. Yet, he has reached an age at which some retire. Beyond extolling a clear passion for the Otago Polytechnic, he offers few clues.

''I'd want to see a strong institution, one able to withstand whatever is thrown at it.

''I think those of us who lead such institutions do so as custodians.That might sound corny, but the minute people like me start to think we own the institutions ... well, we are in deep trouble.''