In 1968, Nobel Peace Prize winner the Rev Dr Martin Luther King jun gave a sermon in which he optimistically suggested that the arc of a moral universe bends towards justice.

A painting hanging in the Dunedin Public Art Gallery’s "Atete (to resist)" exhibition is testament to the fact the arc does not follow an unblemished trajectory. It is Ralph Hotere’s work Black Painting: Requiem for M.L.K., produced following the civil rights leader’s murder that same year.

Social justice issues ran through Hotere’s work, so a few paces from the painting for King is a series about Parihaka, that shining light and shameful blot.

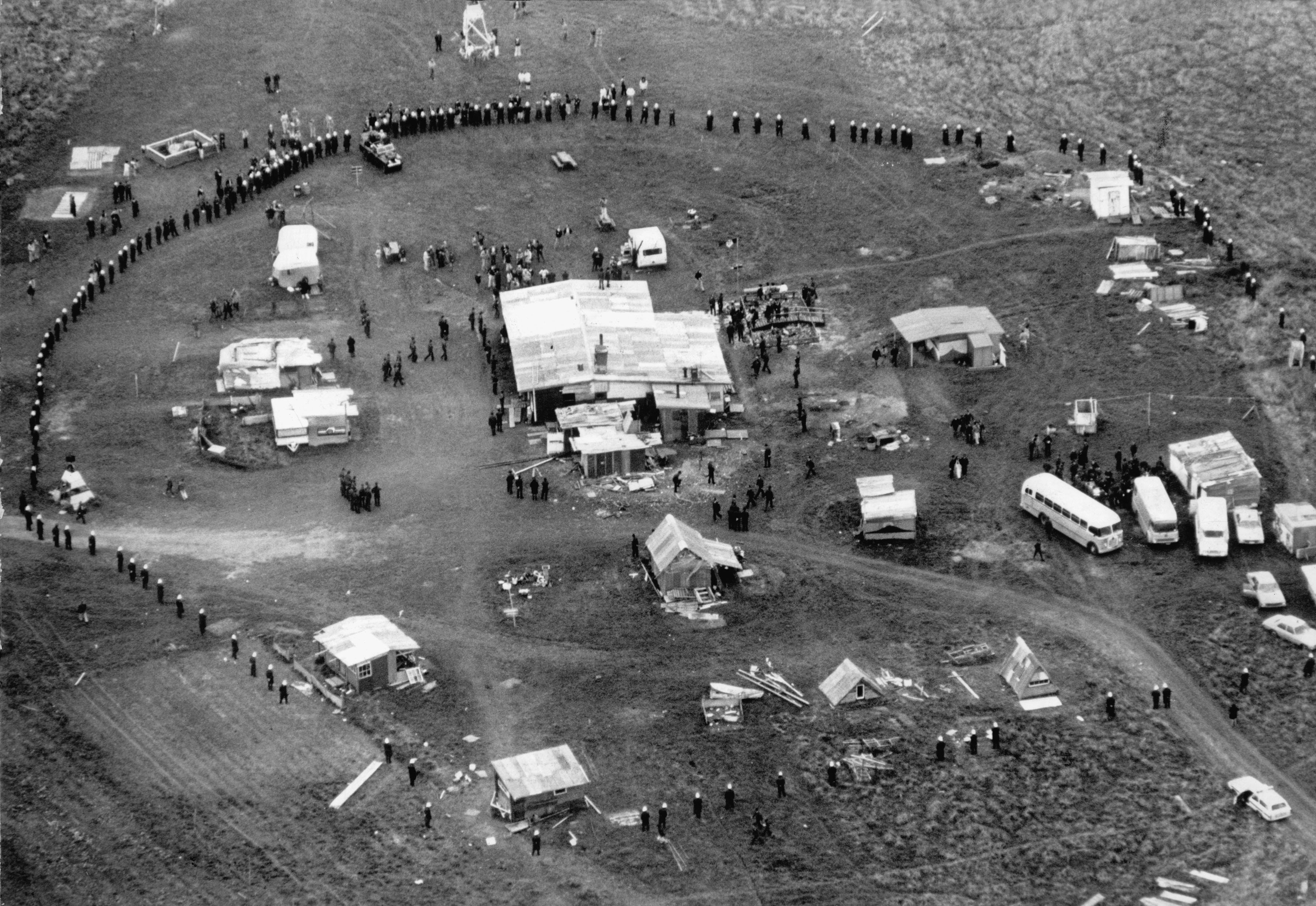

There, in 1881, colonial forces invaded a peaceful Taranaki village, raping, ransacking and burning.

It was another dreadful departure from Dr King’s arc. There have been many in New Zealand’s post-contact years.

It’s a difficult history, but a history better known because of the work of celebrated Kiwi historian Dame Claudia Orange.

Back in 1987, her book The Treaty of Waitangi captured the zeitgeist — it went on to sell tens of thousands of copies — and took the Goodman Fielder Wattie Book of the Year prize the following year.

Fellow historian Vincent O’Malley calls the book a landmark work of scholarship: "In many ways it has shaped how the Treaty has been understood since that time".

It emerged from her PhD thesis of a couple of years earlier, but more fundamentally from a desire to see justice done.

"Really, my driver has been justice, as well as the ability to help the public better grasp our history and the extent to which past events and Maori understandings of their significance vary from the run-of-the-mill grasp of the same. And how that enables us, hopefully, to move forward confidently in future," Dame Claudia says from a quiet room at Te Papa Tongarewa, in Wellington, where she is now an honorary research fellow — having previously been a director, among other positions held.

Building on previous updates of the original book there is now more on the work of the Waitangi Tribunal — which in 1987 had only recently seen its remit extend to cover historic injustices — and the likes of the big settlements, the fisheries deal, Ngai Tahu, Waikato Tainui and Ngati Whatua, along with much else.

As a teenager, Dame Claudia witnessed first hand an earlier government response to Ngati Whatua’s claims on urban Auckland land when in 1952 members of the iwi were evicted from Okahu Bay, near Bastion Point, and their houses and marae burned in an echo of Parihaka.

Her, father, a fluent te reo speaker who worked at Maori Affairs, decided to go down to the bay on the fateful evening to see if anything could be done.

"We drove along Tamaki Dr and paused opposite the settlement, which had started to burn, with the flames visible, women’s voices crying out and a scene of confusion," Dame Claudia remembers. "It was a horrific scene for me. Dad put his head on the steering wheel and cried — the first and only time I had seen my father cry."

A further formative influence for Dame Claudia was the focus on social justice issues among Catholic youth in those years, identifying what might be done and then taking action.

"I think that early training has always made me aware that communities are not always equally balanced — therefore it is absolutely crucial that in some way you are your neighbour’s carer and that’s what keeps driving me on, keeps me interested," she says.

The new book again documents the long years of injustice, raupatu and marginalisation, how the goodwill and prospect of partnership of the 1840 signing of the Treaty soon came unstuck under the pressure of a colonial land grab.

"This is the commencement of our speaking to you," he wrote then. "... we shall never cease complaining to the white people who may hereafter come here."

However, the new sections of The Treaty of Waitangi, on the most recent decades, tell a new tale, one that gives Dame Claudia cause to hope.

"I am optimistic. I would never have thought now at the beginning of 2021 that we would have made so much progress on things when I started that PhD.

"We have made in 40 years a great deal of change," she says.

The new book covers the National years during which Chris Finlayson — of whose commitment as Minister for Treaty of Waitangi Negotiations Dame Claudia speaks highly — brought new momentum to settlements, and on to the establishment of Te Arawhiti, "The Bridge", the Office for Maori Crown Relations.

This last development is one of the reasons for the historian’s optimism.

"Ultimately, what we are looking at now is the setting up of the work of Te Arawhiti, which is a most interesting separate agency in government," she says.

"What we are looking at is quite a revolutionary situation, as we move forward."

It could bring a focus to absolutely crucial areas that still need attention, she says.

Te Arawhiti was set up in January 2019 to oversee the government’s relationship with Maori in a post-Treaty settlement era and has a mandate to both push on with Treaty settlements but also to put the Maori-Crown relationship "at the heart of policy development" for the future.

Achieving that may yet involve further constitutional rebalancing, she suggests, and indeed a Cabinet paper has described part of Te Arawhiti’s function as including advice on "the constitutional and institutional arrangements supporting partnerships between the Crown and Maori".

Treaty settlements have created a range of situations in which power is shared or devolved, in co-management of Department of Conservation land for example, or in mataitai management of coastal areas, Dame Claudia says. Wider society has also become familiar with the application of rahui protections, for example in areas in the North Island where kauri are threatened by dieback.

"Think of the Waikato River and the extent to which the [Waikato-Tainui Raupatu Claims (Waikato River) Settlement] Act in 2010 put in place agreements, that had been made in 2008 actually, to clean up the river and to set up a bicultural body to do it."

That sort of co-management has been quite critical in the evolution of new relationships, she says, of which we’ve become more accepting.

Elsewhere, settlements have granted personhood to the Whanganui River and Te Urewera, giving the Maori world view further recognition in law.

The book quotes Ngapuhi lawyer Moana Tuwhare saying that for many hapu, true partnerships and power sharing are "more important than financial redress in settlements".

"Even though the end result of settlement is great," Dame Claudia says, "it is really only a beginning of working through as a platform for further development of each of those iwi."

It means that what constitutes justice in the New Zealand setting can continue to shift along that welcome arc, she says.

"A lot of people have kicked the bucket and ranted ... I think we are still going to have that," she says. "That’s our nature, isn’t it, not to find change easy. But we are in the process, I think, of quite remarkable change, potentially revolutionary in some people’s mind."

It would be great if everybody, as much as possible, felt comfortable about the changes taking place and saw them as better for the community as a whole, she says.

"That’s not going to happen immediately — it is asking a lot — but I think it can happen."

For Dame Claudia, Ihumatao was another interesting chapter in that process.

"That was a very interesting situation and for a while it kind of baffled me too. But when you think about it, it kind of exemplified so concretely the shift from the land being confiscated after the 1863 [New Zealand Settlements] Act and by 1867 then sold to one family who had held it for so long."

It clearly illustrated the way in which land had transferred out of Maori ownership — in that specific example as part of government machinations preliminary to the invasion of the Waikato — to the benefit of others.

"So much of our land in New Zealand we enjoy because, one way or another, it was originally Maori. Quite large chunks of it have been confiscated."

Between the end of 1863 and the start of 1867, more than a million hectares were taken in "manifestly unjust" confiscations in the Waikato, Taranaki, Bay of Plenty and Hawke’s Bay.

The historian’s view echoes that of an early New Zealand Chief Justice, William Martin, quoted in the book, who said of the Treaty: "We cannot repudiate it so long as we retain the benefit which we obtained by it".

Ihumatao brought forward another group of young, well educated, articulate Maori, Dame Claudia says. A cohort who will be influential in guiding the nation’s next steps.

It is another dividend of the settlement process, because they are intergenerational in their effect, she says.

"When you have younger and more articulate and more educated young Maori coming through they are going to want to look very hard at the sharing of power in the nation."

Piri Te Tau, of Rangitane o Wairarapa, is quoted in the new book about this process of passing on the torch.

"Warts and all, the Treaty process helped us achieve what we wanted to achieve ... Whether we like it or not, it’s the next generation’s turn," Te Tau says. "They do have the education and they do have the time to do what the rest of us have done in our own way in our own era."

Local government is an area where change is much needed, Dame Claudia says.

"The three-year elections, every time they bring up problems."

"That is an area in which it would be good to see some change in the Electoral Act."

Dame Claudia notes various districts are at least talking about setting up Maori wards.

"If that goes through even before any change to the Electoral Act I think that would be advantageous."

At a national level, she notes the challenge still is for the government to be more prepared to work collaboratively with Maori.

That’s consistent with the findings of Matike Mai Aotearoa, a report commissioned by the Iwi Chairs Forum and completed in 2016 after hundreds of hui, that identified various constitutional arrangements — based on Treaty principals — that would provide better Maori representation at a national level.

The report quotes a Waitangi Tribunal finding that the Treaty provided for “different spheres of influence”, allowing for both the independent exercise of rangatiratanga and kawanatanga and the expectation that there would also be an interdependent sphere where they might make joint decisions.

Dame Claudia thinks a worthwhile next step would be a strategy paper on how to develop and expand government comfort and understanding — in terms of policy and action — regarding collaborative working arrangements.

In her book she writes about "constitutional transformation", the same phrasing used by the authors of Matike Mai.

"There is no doubt about it: how we are going to acknowledge the original agreement for the sharing of a partnership in the Treaty, how we are going to work that through ... ultimately, it is going to have to be sorted," she says.

"If we all work together we have a much better chance — as Covid has identified — to ensure we all feel comfortable with what we have and can see the improvements it will make to the nation as a whole."

Dame Claudia does, of course, continue to follow Treaty developments, including the work of the tribunal and the scholarship under way around the country.

Two members of land march heroine Dame Whina Cooper’s family have recently been giving evidence in relation to various matters, she notes as an aside.

Because the Treaty is a living document there is always new research to do; and Maori are always — one way or another — active in the areas that matter to them, she says.

Ngai Tahu’s freshwater claim, the Ngapuhi settlement and the progress of Te Arawhiti are among the things she’ll be watching, as well as developments post-settlement in the Wairarapa and the progress of the proposed Kermadec Ocean Sanctuary, given its potential impact on Maori fisheries interests.

"It is actually pretty hard to keep your eye on everything," she concedes.

"It is an exciting time and it is an exciting time to be an historian."

As for that arc of justice, Dame Claudia can see a path it might follow.

"I would hope so," she says.

It seems to the historian, still, that a well-informed public remains an asset in that effort.

History, she says: "It helps if you know something about it."