We get subsidised doctors' visits and free hospital care. But turn 18, and most of us spend the rest of our lives either paying through the mouth for dentists or suffering the consequences.

Bruce Munro uncovers a national oral health crisis and no ready way to fix it.

These opening sentences could be about Dunedin beneficiary Tamara Smith, whose rotten, broken teeth cut the inside of her cheeks and lips because she cannot afford to pay for a dentist.

Or about solo dad Michael Wilson who cannot afford to get teeth removed and a plate fitted, so lives instead with gum disease and teeth so loose in his jaw that he avoids many foods.

But this is as much a story about waged New Zealanders who are also struggling to maintain oral health in the midst of a crisis of unmet dental need and out of reach dental fees.

People like Sam Parkes, a Dunedin builder who is married and has two children. His wife is also in paid work.

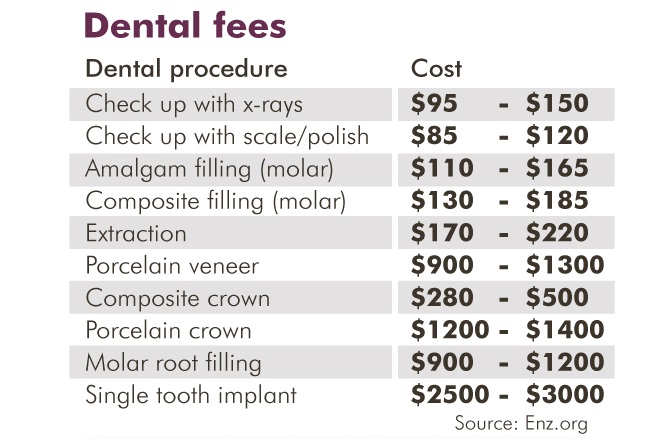

Parkes' most recent trip to the dentist was the first in about eight years. A check-up, a filling and a clean cost him $645.

He only went because, after two years of avoiding the inevitable bill, the pain in his tooth drove him to make an appointment.

His dentist has told him there is other work that needs doing, including x-rays to see if wisdom teeth need to be pulled, at $300 to $600 per extraction.

Parkes says he is unlikely to go back any time soon. "When it comes to the dentist, no-one's ready for those bills.''

The Otago Daily Times (ODT) went looking for a story on the cost of dentistry. It wanted to know whether it was time to publicly fund adult dental health care. What it found, was a mountain of need and almost universal recognition that it will not improve for the foreseeable future.

Before the facts, came anecdotes.

On the ODT Facebook page, a request went up. "Do you have a big dental bill? Is the cost of going to the dentist stopping you getting those sore or broken teeth seen to? ... [We] would like to hear your stories.''

In they came, like a flood of bloodied mouthwash spat into the dentist's chair-side sink.

"Dentists are far too expensive,'' Kelly Mulvena, of Clyde, posted.

"Cost is the reason I put it off until I'm in so much pain I can't tolerate it anymore.''

"I haven't been since my last free visit ... 10 years ago,'' Cher Forgeson, of Dunedin, wrote.

"Can't really afford to - always something more important like rent or food to get.''

"My husband had to go to the Dental School to get wisdom [teeth] cut out last year,'' Kelly Gascoyne, of Dunedin, added.

"Total bill cost over $700 dollars. We are still paying for it $10 a week. Family of five - it's expensive. All three of my kids are going to need braces and they are very expensive.''

Some comments were positive, sort of.

"Have a great dentist,'' Sefo'n Janferie Kelekolio, of Dunedin, wrote. "Had a bit of trouble of teeth breaking. Found out that to get a bridge done between two teeth (over a gap) will be in the thousands. So I'm hoping they don't get run down too quickly as I'm still paying off a root canal that went wrong.''

Even those with a bit of money had something to say about the cost.

"My dentist is in SE Asia,'' wrote Timo Costelloe.

"The cost of going to the dentist in NZ is prohibitive. I get a holiday and a dental visit for less than it costs to go in NZ. I have a great dentist, trained in Korea.''

Experiences were shared from all over the motu.

"I have about 12 to be pulled,'' Courtney Louise, of Christchurch, wrote.

"Two are broken at the gum, with skin starting to grow over. But I refuse to go because of the cost and they chip away. Sore every now and then but it's far too expensive with having so many to be pulled. Just don't have money even though half the time I feel like I have an ear ache 'cause of my back tooth.''

Dozens of personal stories.

And then the facts backed them up.

MURRAY THOMSON is professor of dental epidemiology and public health at the University of Otago. He counts teeth and has lots of graphs measuring tooth decay.

The situation is not good, Prof Thomson says.

Until a decade ago, the rule of thumb was a 50-50 split between those who went to the dentist for regular check-ups and those who only went when they had a problem, he says. But the most recent National Oral Health Survey, done in 2009, shows that less than 40% of adults now routinely visit their dentist.

Into that equation, he adds the latest findings on tooth decay.

"We used to think that the decay rate was relatively low for adults. We now know from the Dunedin Study, it is a bit higher in childhood, then pretty much constant for life before increasing again in old age.''

On average, people get one new decayed tooth surface per year.

If most people are not going to the dentist until a tooth begins aching or breaking, but they are getting new decay every year, then "we are storing up problems for the future,'' he says.

And, of course, some people are getting more decay than others.

Prof Thomson and Assoc Prof Jonathan Broadbent, of the Faculty of Dentistry, have both been involved with the internationally significant Dunedin Study; a multidisciplinary health and development study that has tracked the lives of 1000 people since they were born in Dunedin in 1972 and 1973.

Prof Broadbent says a key finding, from a dental perspective, is that by the age of 38, people born into disadvantaged families have lost six times as many teeth as those born into well-off families.

That is reinforced by the results of the last National Oral Health Survey, Prof Thomson says.

"We got good at measuring people's quality of life in oral health terms. The most deprived 25% of neighbourhoods have almost three times as much tooth decay as the least deprived quarter of neighbourhoods.

"It affects people's quality of life, it affects their day-to-day functioning. They are in pain. They might not be sleeping. They might not be able to get a job because their teeth don't look that good.''

That inequality, and its damaging effects, has been exacerbated in recent years.

"Over the last three parliamentary terms we've seen an increase in poverty - more and more people in financial stress - because of a lack of the trickle-down we were all promised,'' Prof Thomson says.

BUT it isn't just the poor who are struggling to maintain their dental health.

Megan Blok responded to the ODT request for dental stories.

She and her partner are down to one income because Blok, who is 19 weeks pregnant, has had to take a break from work to nurture the new life within.

But even when she was working, going to the dentist was an unaffordable luxury.

"Dental health affects so much of your life,'' Blok says.

"Even just the way you look for starters. When you've got massive holes in the front of your teeth ... people judge you for that.

"But it's also the infections if you don't get them seen to because you can't afford to.''

Her salvation was the University of Otago School of Dentistry, which gives half-price treatment to patients seen by trainee dentists.

"It still cost me $900 and took two years to pay off.''

More dental work is needed. But she keeps delaying treatment because of the cost.

"I brush my teeth every day and do all the things you are supposed to do. My problem is that I drank sugary grape juice during my teens.

"I can't afford to go and get my teeth fixed. On a basic income, with rent and food and so on ... it's basically unaffordable.''

So, she has a drastic remedy in mind. "I'm planning on getting them all pulled out and dentures done.''

She will wait until a couple more teeth fall out and then bite the bullet for a full mouth extraction. "It is a drastic step. But it's a hell of a lot cheaper.''

She's not alone in her extreme plan. "I know a lot of others who are considering doing the exact same thing because it is just too expensive to maintain ordinary teeth.''

The state of dental health in New Zealand can be likened to the proverbial frog in the slowly boiling pot of water.

"We maybe haven't realised how bad it is,'' Prof Thomson says.

"We've got used to the fact that people are missing out.

"And if the dominant discourse is that it's all their own fault, which is certainly put out there by particular political parties and groups, then it makes it easier for us to ignore that.

"There is a lot of untreated suffering out there.''

AN OTAGO dentist got in touch to suggest an article incorporating people's stories about the cost of dentistry could be "further fuelling the fire of hate towards dentists''.

"How about explaining why it's expensive'' he said.

"People don't seem to understand that running a dental surgery is like running a mini hospital. There's registration fees, staff, sterilisation, materials cost. A dental chair is upwards of $70,000. My drills cost $2000.''

The dentist says he bends over backwards to help people, "but there are overheads''.

"There's no government funding. When they go see a GP and they pay $60-odd for a consultation, there's a larger hidden fee covered by the Government.''

When invited to give more comment, the dentist declined and said he did not want his name used.

But before signing off, he agreed there was a problem with New Zealand's dental system.

"Of course it's time to publicly fund it,'' he wrote.

"Ask any good New Zealand dentist and they want it funded. I want it funded.

"The current system is not working.''

A total fix, however, looks impossible. The problem has got out of hand. The crisis is too big to solve.

Prof Thomson says the best estimate is that $1.8 billion is spent on dentist visits each year in New Zealand. And almost all of it, $1.6 billion, comes directly from punters' pockets.

Only $242 million, 15%, is paid for by the State.

But don't forget, Prof Thomson says, that New Zealand's dental health care system "has evolved to meet the demand, not the need''.

With less than half of New Zealanders routinely visiting the dentist, and one new tooth decay, per person, per year, any attempt to meet even just the year-to-year need for dental work would cost twice as much as is presently spent.

"If the Government decided tomorrow to bring in a fully-funded system for people who needed dental care - even assuming only 85% would take it up because we've got 15% of people who are so deadly anxious they are not going to go near a dentist - we wouldn't have the capacity in terms of workforce and surgeries.''

And that is not even taking into account the accumulating mountain of need as a result of people putting off going to the dentist for several years.

Whether from the private or public purse, the money is not there.

It is simply not going to happen.

HOW did we get here? Why is hospital care free of charge and a visit to the doctor heavily subsidised, but a trip to the dentist not a part of government adult health care funding at all?

Prof Tom Brooking wrote a book on the subject, literally. In 1981, the University of Otago historian wrote A History of Dentistry in New Zealand.

Pulling the book off his shelf, Prof Thomson explains the back story to where we are today.

In 1938, Prime Minister Michael Joseph Savage used the Social Security Act to establish the country's much-lauded welfare state.

Free medical care was introduced through that Act. Part-funded GP visits were part of the deal.

"At the time, the understanding was that dentistry would follow in due course,'' Prof Thomson explains.

It never did.

The ultimate aim was to have a salaried service, that is, the Government employing all dentists. But it was opposed by dentists.

"They were very organised in resisting it,'' Prof Thomson says.

"They didn't want to be socialised. They had only just come of age as a profession. And their status and autonomy was very important to them.''

Also in the offing was a proposal to means test poor adults and give government-funded dental care to those who qualified.

"But that never happened either. The compromise was that it [funding] was extended beyond intermediate school to secondary school kids.''

It is, in essence, the same situation we have today; free dental care (except for orthodontics) up to the age of 18, and then practically nothing.

Prof Thomson says our school dental service has been the envy of the world, copied by countries including Australia, Malaysia and Singapore.

But our adult dental system is "social Darwinism written large'', he says.

"The United States is a case in point: if you are well off, dental insurance is probably included in your employment benefits package. If you are not, you're probably in real trouble.

"We're a bit like that, except we don't really have dental insurance here. It's pretty much, if you can't afford it, you don't get it.

"Work and Income do have $300 special needs grants to deal with immediate problems. I tend to refer to it as State-sponsored incremental tooth loss. Because, really, what can you get for $300 except a tooth out?''

In response to our dire situation, the best we can hope for is to help the worst off; the poor and the elderly.

But even that will not kick in for at least three years.

For the first time, improving oral health has been included as a goal in the national Healthy Ageing Strategy. Moving that from goal, to policy, to implementation is likely to take a few years, Prof Thomson says.

As for those on the lower rungs of the socio-economic ladder, Health Minister Dr David Clark agrees there is "a huge unmet need in dental care''.

"We have people struggling with Third World health conditions as a result of bad dental hygiene and inability to access the care and treatment they need.''

He would like to see more affordable access.

"But as I've said before, it's unlikely we'll get significant change over the line with that this term.''

ACCORDING to those in the know, the most likely scenario is the staged introduction of subsidised dental care for those with a Community Services Card, starting sometime after 2021, if Labour remain in government.

That fits well with how the New Zealand Dental Association views the world.

Dr David Crum, chief executive of dentists' professional body, says the system is not broken, the expense of dental care is largely a matter of perception, and a mix of helping hand and personal responsibility is the ideal way forward.

During the past 20 years there has been a huge improvement in adult dental health, Dr Crum says. Tooth loss and dental decay rates have both dramatically decreased.

"The system is in good shape for many. It's not for some,'' he says.

"There is still high rates of dental disease among low-income adults.''

Going to the dentist is only perceived to be hugely expensive because it is compared with going to the doctor, he says.

"That's not surprising, because when you go to the doctor the Government is picking up most of the tab. When you go to the dentist they are not picking up any of it.''

But some people do have genuine difficulty affording dental care, he says. For them, he favours partially funded trips to the dentist.

"There needs to be some publicly funded money put in there to safety net those that actually, really need it.

"And I'm not just talking about people who have got the wrong priorities - the New Zealanders who spend $800 million a year on pokies - I'm talking about people who actually, really need it.

"The safety net for the most vulnerable ... needs to retain some form of co-payment, so that there is value attached to the service. Because in the end, all dental decay is preventable.''

Dr Crum says big improvements in dental health would come from fluoridating all drinking water and introducing a sugar tax.

"I know you don't want to hear that, but ... that's more important than providing endless amounts of money to treat dental decay.

"But it's a hard message to sell.''

It's true. The easier one is bashing the poor. But it is not an approach Prof Thomson has much time for. Despite being raised in Huntly on the wrong side of the tracks and bucking the stereotype, exercising self-discipline to ensure he has not had a single decayed tooth in 35 years, he takes an empathetic approach.

"That old Tory trope: why do the poor behave so poorly?'' he says with a laugh.

"Of course, that's what some people will say. But you can predict the disease experience of 30 year olds on the basis of their mother's oral health. This underlines the issue of intergenerational continuity in oral health.

"If you have poor oral health as an adult, your children, because they are growing up in the same conditions, practices, beliefs and values, are much more likely to have poor oral health themselves.''

There seems at least some hope that they might get some help, some time.

For the rest of us, personal responsibility sits heavily on our shoulders.

"There's no quick, easy answer,'' Prof Thomson says.

"We just have to prioritise it among all the other competing demands for our household expenditure, I suppose.''

He suggests taking all the usual measures to stay dentally healthy: don't smoke, don't have sugar in tea and coffee, don't snack between meals, clean teeth twice a day and clean between teeth a few times a week.

"Also, use a fluoride toothpaste. And, choose your parents well.''