Creating New Zealand was a novel experiment, informed as it was by time and place, Emeritus Prof Erik Olssen tells Paul Gorman.

Experiments aren’t always carried out in a laboratory, with people in white coats and bubbling test tubes.

Sometimes they take place in the real world, in real time — social experiments aimed at changing societies and, if they have the best of intentions, making a fairer world.

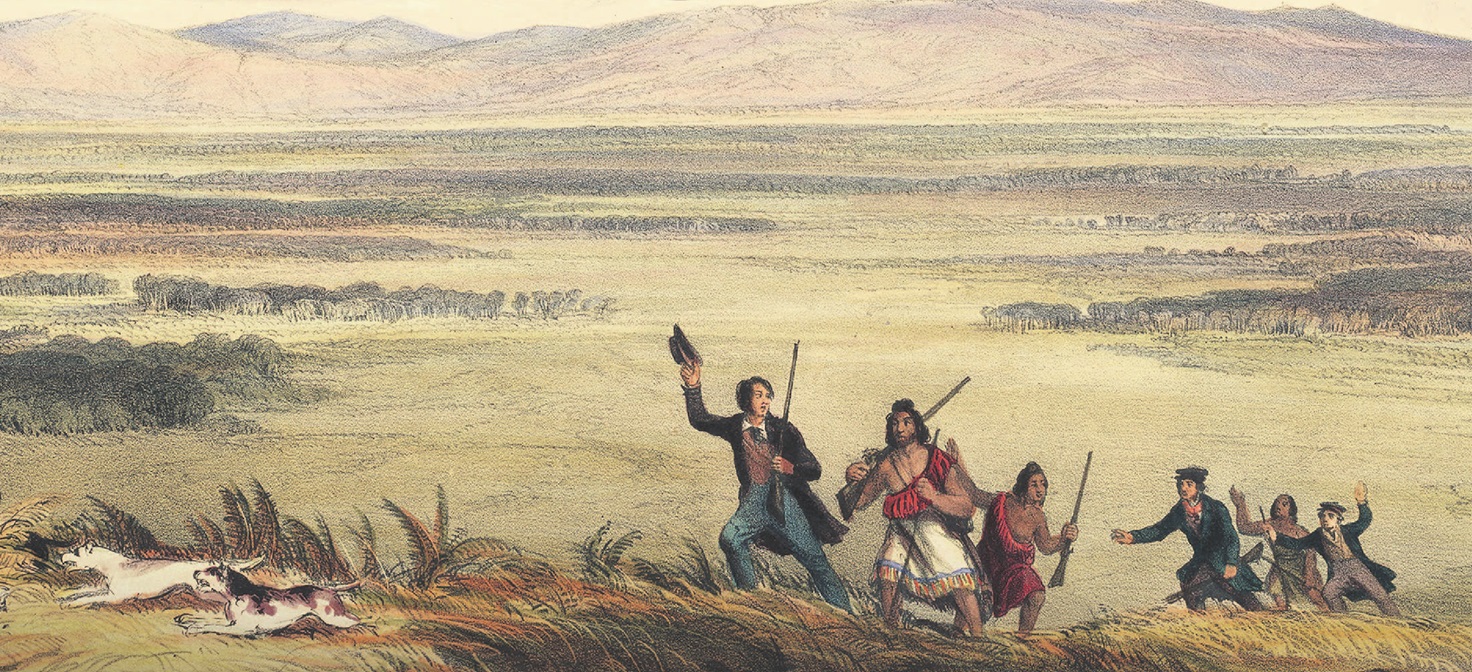

Then there was European colonisation, a social experiment that played out across the globe in the second half of the last millennium.

It was often brutal and unethical, resulting in the deaths of millions of indigenous people and the loss of their cultures.

Repercussions from such repressive, murderous colonialism still ripple through those communities.

Aotearoa in the 18th and 19th centuries was also the scene of an experiment, one that took place within that context of colonisation, but a far more benign experiment, argues Dunedin Emeritus Prof Erik Olssen in a book released this week.

The Origins of an Experimental Society: New Zealand, 1769-1860 (Auckland University Press) is the first of three planned volumes by the University of Otago historian, whose research cuts across politics, society, ideas, culture and economics.

The book focuses on how Pākehā settlers, imbued with evangelical humanitarianism and brought up on the Enlightenment school of thought in the 18th century, met and interacted with Māori and how both peoples worked together to develop a "distinctively experimental society".

Colonisation post-James Cook’s arrival in 1769 became one of the few post-Enlightenment experiments in building a new country anywhere in the world, Olssen says. European settlers had new-found belief in the powers of reason and experience to improve peoples and societies.

They hoped Māori would not be driven to extinction but take their place as equals in a modern commercial society, a "Better Britain", one fairer and more just than the one they had left behind.

"In turn, Māori adapted these new ideas to their own ends, giving up slavery and inter-tribal warfare, and adapting the institutions of the colonisers in ways that would re-define the experiments," the book’s media release says.

"This then is an ethnography of ‘tāngata Pākehā’, a people of European descent changed by their encounters with ‘tāngata Māori’ and their land — just as Māori themselves changed — and the story of the society they built together."

The book’s introduction sets the scene:

"The islands of New Zealand were colonised by two seafaring peoples, the Polynesians from around 1350 and the Europeans from the early 1800s. In 1642 the Dutch sailor Abel Tasman arrived. "Had his first brief contact with Māori led on to further European arrivals in the same century, New Zealand’s history would have been very different; but Europeans did not return until the late 18th century, in the so-called "Second Age of Discovery", and this second arrival coincided with the intellectual transformation now commonly known as the Enlightenment.

"This book contends that the timing of encounters between tāngata whenua and Europeans, and the European colonisation of New Zealand, has profoundly shaped its subsequent history. While that history echoed the broad shape of earlier colonial histories in other places, particularly in other settler societies, it also diverged and took its own course in important ways."

Talking to The Weekend Mix, Olssen says he is aware the findings of his book may not resonate with current views of colonisation and the harm it has done.

"It possibly will attract the ire of some people. I mean, I’ve called it an ethnography of the Europeans, and I want to make it clear that, especially in the North Island, they’re interacting with Māori so extensively, and Māori were so central in a sense to the [New Zealand] Company’s view of what New Zealand was about.

"I hope that weakens the sense of ‘he’s just trying to justify colonisation’. Some people like that are ... probably not going to read it."

Putting together such a large volume of history from primary and secondary sources is an intellectually challenging task, even for an experienced academic.

Olssen says that, originally, he was going to devote the 1990s to the book.

"It was an idea in the back of my mind, really. It began as a short history of New Zealand, centred on the fundamental argument that what is distinctive about a neo-European society is that it’s thoroughly post the Enlightenment. So, people will no longer look back to tradition for answers — they’re pretty suspicious if you suggest that that is going to help them find an answer to a problem."

Academic and departmental matters then interceded, but during a summer fellowship at the Australian National University in Canberra in 1997-98 he completed a draft, "though I wasn’t very happy with it".

After retirement in 2001 and other book projects, Olssen, now 83, knuckled down and worked intensively on the book from about 2013 till 2016. He says he now has a pretty good draft of the second volume, covering from 1860 to the end of World War 1, and has a rough draft of volume three, which will run from then until more modern times.

He faced many challenges in compiling and analysing so many documents across different subject areas, including reading French expedition accounts to New Zealand in their own language, and carefully interpreting and reinterpreting historical sources. There was also the need, as an academic, to maintain intellectual curiosity over many years, avoid making assumptions and writing simplistic narratives about class and race, and to keep up with emerging findings.

It would be easy to feel daunted by such a vast project, wouldn’t it?

"Well, I enjoy the writing. Maybe I just realise now the world’s vastly more complicated, so it’s more difficult writing. When I was younger it was simpler and quicker to write. But I’ve always enjoyed writing and drafting, and I can get lost in it. If anything is going wrong in the world, I can lock myself in my study and I don’t even think about what’s going on.

"I don’t work at night anymore, except in a total emergency. Writing in the morning is my ideal life — write till lunchtime, might do a little bit in the afternoon. If a bright idea comes to me, I’ll try to grab it while I’m thinking of it, before it disappears. But I’m not a very good touch-typist."

The book was a matter of "bringing stuff together", he says.

"The first taproot for the project was, ‘Is there a New Zealand political tradition?’. There’s quite a lot on it for the 1890s onwards, a time of social reform, but there wasn’t much for the 19th century. And so, thinking about that, the founding fathers — more fathers than mothers — such as [Edward Gibbon] Wakefield and co, began to attract my attention.

"The second taproot was when I was at high school, and the same at Otago [University], you couldn’t do New Zealand history. There was an MA paper which looked at British imperialism in the Pacific, and that included some New Zealand stuff, but that was it.

"That didn’t interest me, but I did do a master’s thesis on New Zealand history. I couldn’t think of a topic, but I was sitting around in the student café and this guy said, ‘oh, you should do John A. Lee’. So I did, and that became my first book.

"There used to be a joke that there was so little written about New Zealand history that was acceptable to scholars that you could read it all in one summer, while babysitting."

Olssen had much of the material when he started writing, or so he thought.

"A friend who read chapter one, on Cook’s voyages, said to me, ‘I think you need to say a bit more about what they thought about the Māori’. As soon as he said it, I thought, yeah, well that’s true. And that became a massive rabbit hole, because the English were really more obsessed with class, and they weren’t interested in race.

"I had to master a whole lot about attitudes to race then that I wasn’t going to be including in the book. It took me time to realise the English cared about class and the North Americans were more concerned with race."

With the book covering so much ground, it’s hard to know where to start with an overview.

In the book, Olssen says New Zealand’s history as a new nation, dominated by British settlers, is distinctive "precisely because it became entangled with the ferment of ideas generated by the Enlightenment and the scientific revolution, both of which stressed the ability of humans to use reason to manage the world and improve both themselves and their society".

Olssen told The Mix he was particularly fascinated by several individuals, including Cook, Edward Gibbon Wakefield and Bishop George Selwyn.

"I tracked down papers generated by the last two still held in private hands by descendants in England. I also came to think that their historical importance had been dismissed too completely."

Wakefield — whose chequered past included a conviction for kidnapping a 15-year girl — had been planning two church-based colonies in New Zealand. One was to be Scots-Presbyterian, involving a vision of a "New Edinburgh"; the other Church of England, eventually the Canterbury Association.

In 1846 Charles Kettle, a native of Kent who had learned surveying in Wellington before heading to Scotland to promote the Otago Association, was chosen to survey Dunedin. He used novel trigonometric techniques in designing a townscape that adapted the rectangular grid to a difficult site while making provision for "Public Buildings, Sites for Places of Worship and Instruction, Baths, Wharfs ... Cemeteries, Squares, a Park, and other places for health and Recreation", including an extensive town belt that enclosed the future city within an irregular crescent of native bush.

Leading up to 1840 and the signing of Te Tiriti o Waitangi, Māori were expected by the William Hobson administration to help shape the course of events and be protected by it, Olssen says in the book.

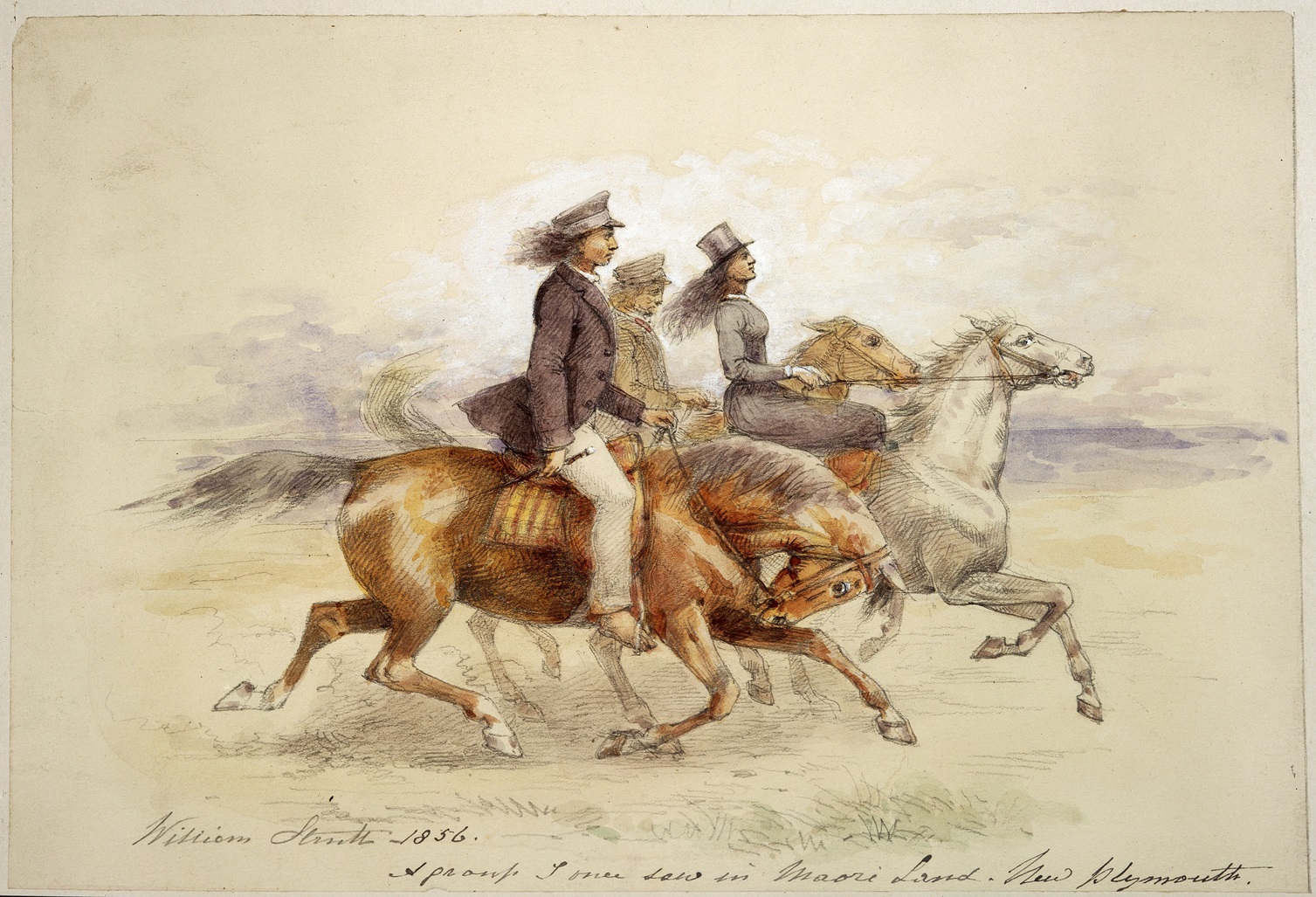

Where Māori and Pākehā children grew up together or married, they learned enough English and Māori to move quite easily between both worlds.

Over the same period, 1800-1840, the tribes had to achieve a larger sense of unity, prefigured as it was in the increasing use of the word Māori to differentiate themselves from Pākehā, their word for the polyglot mix of nationalities who arrived on their shores.

Although Hobson’s administration consisted of the normal officers — a judge, a superintendent of police, a surveyor general, a colonial secretary and a treasurer — he was also instructed to appoint a Protector of Aborigines and to be guided by the imperial government’s determination to protect the "Aborigines of New Zealand" from the evil consequences of colonisation, while assisting the missionaries in helping this most remarkable people continue their advance from "barbarism" to "civilisation".

Olssen points out the awareness of women’s importance in settling the new country, with Wakefield’s observation that "an unbalanced sex ratio" was "the fundamental source of the pathology of previous frontier societies".

Hence, young married couples and a roughly equal number of young single men and women became central to systematic colonisation.

Although E.G. Wakefield agreed with Adam Smith that women’s economic contribution was of little importance, he also agreed with John Millar, a luminary of the Scottish Enlightenment, that the status and position of women in any society was a measure of that society’s sociocultural development and refinement.

New Zealand’s temperate climate and fertile soils quickly attracted plants from around the world. Horticultural societies proliferated and domestic gardens soon became part of Wakefield’s experiment. Protestant mission wives had set the trend, planting honeysuckle and roses, as well as almost every fruit and vegetable known in Britain. Church cemeteries also became adorned with flower beds and ornamental shrubs. "Making roses grow where no flowers grew before," as Auckland’s first harbourmaster remarked — providing a picture postcard summary of colonisation together with its justification.

That well-tended image was not without its challengers.

The labourers’ revolt of the early 1840s proved enormously significant and challenging to the experiment here of a "Better Britain", the book says.

Promised plenty of work, wages, access to land and free medical assistance, labourers soon found wages and rations cut because few capitalists had also migrated. Nelson’s labourers summed up the issue, saying if there was no work for them they had still been guaranteed one guinea a week with rations.

"We do not want large fortunes or Extraordinary Incomes but to live Comfortably and decently."

Dissatisfied with the lack of response, and furious when their wages were not paid, a "disorderly mob", many of them armed and "inflamed with alcohol", rioted. On another occasion, furious labourers threw their supervisor into a ditch. Many of those dependent on selling their labour took their cue from settler Chartists and socialists, and now thought of themselves as "the working men" or even "the working class", a novel collective identity that signalled a shift from a social order based on rank to one based solely on occupation. The well-to-do panicked.

Did the great post-Enlightenment "experiment" in New Zealand work? In Olssen’s view, it was a mixed outcome.

"In terms of experiment one — to protect Māori in developing a new society — that did work, though I think we would now say perhaps they (settlers) were excessively gloomy, and that Māori wouldn’t have died out regardless of what had been done to them.

"They had been very obsessed with, or preoccupied with, the fate of the Amerindians, especially the Spanish conquest of Central America in which millions died. So, they thought this was inevitable, but were certainly anxious that it did not happen. Because right from Cook, contrary to Tasman, they held Polynesians in general and Māori in particular in very high regard.

"The second experiment was to make a better Britain. Right now, for somebody my age, if you’d asked us in about 1980 or ’90, we’d probably say, ‘yeah, we’ve done that’.

"But sitting here 30 or 40 years later, you read about the meth and the violence, the poverty and the homelessness. So, probably a question mark on that one."