"To be frank, that’s exactly what they experienced when commissioners were appointed in Tauranga," the voice on the phone says.

"Decades of deferred investment" resulted in rates going up by "enormous amounts, eye-watering amounts, really".

"What tends to happen is . . . councillors are elected on a promise to keep rates low. They do a reasonable job of that — by deferring the needed investment."

So, they get elected and reelected, Voice A says.

But, by the third term, chickens can be heard in the roost.

"Then they stand on ‘Vote for me because I’m going to fix this problem’ — which they created, but no-one’s the wiser.

"And then they say ‘Well, sorry, the only way we’re going to be able to fix this is to put up the rates an enormous amount’.

"That’s been the decision-making process in many parts of the country. That’s how they got to this state."

These are not the words one normally hears uttered by city council bosses, high profile politicians, top-ranked civil servants. Not out loud. Not unless you move in those circles, are privy to those unguarded conversations.

But they are the conversations being had, so The Weekend Mix is told, whenever New Zealand’s drinking, waste and storm water — its Three Waters — infrastructure is discussed behind those closed doors.

Three waters — the more than $70 billion worth of reservoirs, pipes, ponds and treatment plants that deliver drinking water, channel storm water and remove waste water — is one of the country’s most significant infrastructure sectors. Most of 339 water treatment plants, 42,559km of water supply pipes, 1030 pump stations, 18,452km of stormwater network and 327 wastewater treatment plants are owned and operated by Aotearoa’s 67 local authorities. Almost 5000 people are employed to support the delivery of these services to 4.3 million people.

And all of it is in the middle of a massive shake-up.

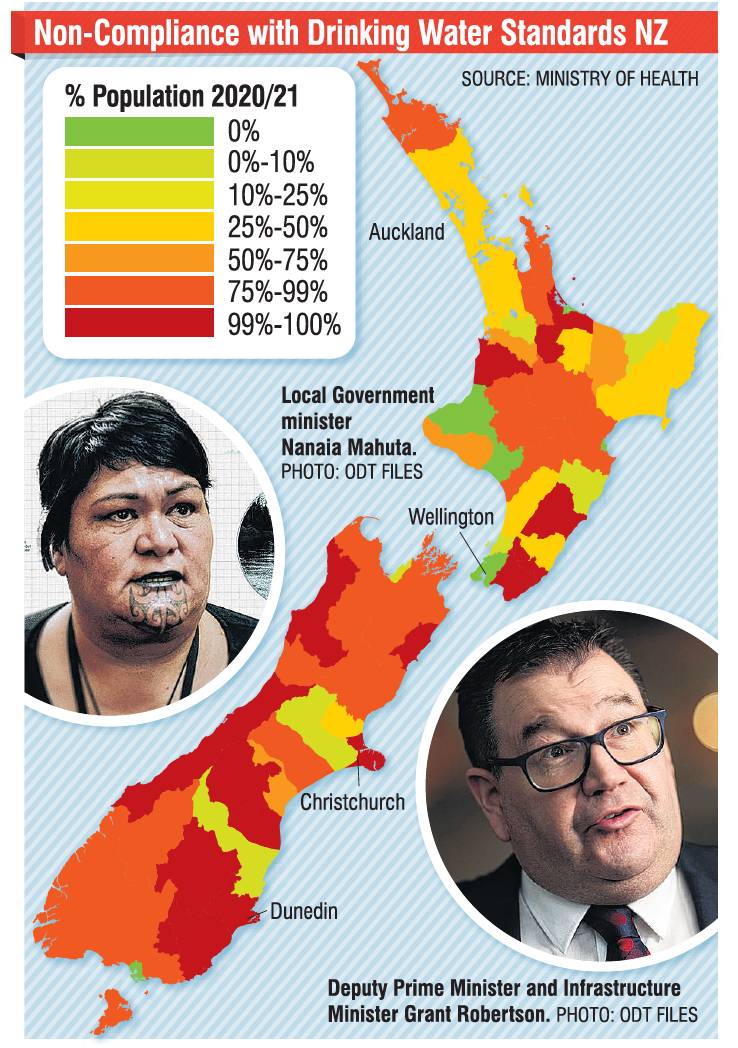

In response to the 2016, Havelock North campylobacter contamination that infected 8000 people, killed at least four and left others permanently disabled, the Government took an urgent and hard look at water services in New Zealand.

Now a new national body, Taumata Arowai, has been set up to regulate drinking water. It will also oversee the environmental performance of waste and stormwater networks.

To enable that and other changes, the Water Services Bill was passed into law last October.

It is not to be confused with the Water Services Entities Bill, now in the parliamentary pipeline. This Bill will establish four publicly-owned, geographically-defined, entities that will take over the ownership and operation of the local authorities’ three waters infrastructure. Entity D will cover all of the South Island, except Tasman, Nelson and Marlborough.

Three Waters will be managed using a co-governance model. Representatives of local government councils and mana whenua will jointly appoint regional representative groups to manage the entities’ strategies. These groups will also appoint independent selection panels that will appoint the boards to manage and run each entity.

The aim of it all, Local Government minister Nanaia Mahuta says, is to use economies of scale to allow the extensive and ageing water infrastructure to be affordably managed and upgraded, giving New Zealanders improved three waters service delivery, including cleaner, safer, more reliable, drinking water.

However, since the moment the $761 million Three Waters reform was announced more than two years ago, it has been embroiled in fierce debate, polarising controversy and apparent policy flip-flops.

Some councils opted out of the whole plan. Most councils expressed concerns, particularly about ownership and governance.

The Government offered councils a $2.5 billion sweetener to opt in, but also added it might force councils to toe the line.

In October, last year, the Minister set up an independent working party to review the whole plan.

Six months later, Mahuta and Infrastructure Minister Grant Robertson announced the Government would push ahead with the reforms but would give local councils non-financial shareholdings in the four public water entities. Governance, though, would still be a 50:50, council-iwi, co-governance arrangement.

Three Waters’ due date is July 1, 2024.

In the meantime, the Entities Bill is progressing through Parliament, councils continue to express a mix of agreement and alarm, the issue has become a local government election football, and many in the general populace feel Three Waters has become thoroughly muddied.

"That is why I was keen to do this interview with you," Voice A says.

Not that they were keen from the start.

Contacted because they had extensive knowledge of the background to Three Waters, they replied that for that very reason they could give no comment. Given the option of speaking off-the-record, however, they suggested a time the following day.

The same went for Voice B, selected because they had been, but were no longer, sitting at the table where Three Waters issues were debated and thrashed out. That degree of separation was not enough for them to feel comfortable speaking on-the-record. But they offered to talk frankly if their name was not published.

So, I think many have had conversations where the pressure to both do stuff and keep rates down has meant they have underfunded three waters assets

By the time Voice C — who has held some of the highest offices in Aotearoa — was contacted, the tongue-loosening benefit of anonymous commentary on Three Waters was well established, and offered immediately.

And so the "unmuddying" began.

Those spoken to are in clear agreement that change is needed because, on the whole, local councils have not been good stewards of their Three Waters infrastructure.

Here is how it has played out, Voice B says, elaborating on the scenario outlined by Voice A.

"I think you would find most chief executives, and probably a fair few mayors, around the country would admit that every year councils get harangued by, on the one hand, a line of people saying ‘Keep the rates down’, and on the other hand, a line of people saying ‘We want a cricket pitch, we want cycleways, we want a library, we want an arts theatre. . .’."

And both those competing promises get councillors elected.

They all know affordability is an issue. So, they all promise to find ways to cut costs — "We’ll cut the low hanging fruit, we’ll cut staff; because somehow they pretend staff aren’t actually doing the work".

For most councils, there isn’t any low hanging fruit. But you have to promise to find and cut it, otherwise no-one will vote for you, Voice B explains.

"So, for decades, I’m pretty sure every chief executive around the country will have had conversations [with council staff] asking, ‘Can’t you just put off that water main renewal? Can’t we just delay that for a couple of years?’. Because then you can deliver the cricket pitch and not put the rates up."

And here is how it has consistently impacted on water infrastructure.

"We know the pressure means they [councils] find things to not do that people won’t notice, that people won’t see."

Such as, the maintenance of underground pipes and the removal of microscopic waterborne contaminants.

"So, I think many have had conversations where the pressure to both do stuff and keep rates down has meant they have underfunded three waters assets."

The Government has been aware of that, Voice B says.

And, it has decided to take action to ensure Three Waters are no longer at the mercy of political pressures.

Hence, the Three Waters reforms.

Interestingly, Three Waters is not something Labour dreamed up in a caffeine-fuelled, Covid lockdown, brain-storming session a couple of years ago. The broad brushstrokes of the reforms have been in the works for a decade, Voice A says.

It was about 2010 when Infrastructure New Zealand and Water New Zealand, two leading industry bodies, started working on the case for water reforms.

Together they were looking for "the best structure to deliver high quality three waters to communities across New Zealand", Voice A says.

Independently the two associations explored international three waters models in countries with similar legal and democratic systems to New Zealand — the British privatisation model as well as the Australian and Scottish corporatisation models — and then compared notes.

What was immediately obvious, Voice A says, is that size matters.

"In the provision of water services, scale really makes a difference. You’re talking about a major infrastructure investment in an increasingly technologically-driven context, meeting national water quality and environmental standards.

"Many councils lack the balance sheet capacity to be able to invest at the scale required; particularly small councils in rural areas.

"When you’ve got the need to invest in some legacy assets that are now very old and no longer meeting standards — a huge requirement for investment, let alone the challenge of increasing water quality standards, improving environmental outcomes and coping with climate change — it became pretty clear that the current structure was not going to be able to deliver."

Britain’s privatised, profit-driven model did not sit well with the New Zealand ethos. Scotland, on the other hand, shared many similarities with New Zealand — local government-run water infrastructure; lots of small, rural councils; ageing assets; and, a desire to add value.

Scotland’s first water reform iteration had four regional governance entities, similar to what is proposed for here. They saw some improvement. But it was not until the Scots turned the four into one, Scottish Water, that they got big gains, Voice A says.

Voice A believes New Zealand should learn that lesson and go straight to the one entity.

"They achieved a remarkable result. As I recall . . .within a decade, they had reduced their operating costs by 40%, which is enormous savings.

"That was quite significantly driven by smart capital investment programmes; a major shift to technology with remote monitoring of pumps and systems."

The Scots benchmarked themselves against the English — setting themselves a target to become at least as good as, if not better than, the privatised companies.

"They were able to lift performance standards in terms of quality of water and customer service standards, while actually reducing costs.

"That was a pretty amazing insight into what was possible."

While Voice B agrees with the need for reform, they say a lot of the angst and opposition has come from how it has been implemented.

It would have helped hugely if the Department of Internal Affairs (DIA) had narrowed reform options to a few possible models and then worked with local authorities to explore costs, benefits, risks and preferences.

"Then they could have said to the sector, ‘We’ve done all that work with your people and here’s the one we’ve settled on’.

"They didn’t do that. They just made the decision; ‘Here’s the Three Waters model. This is what we’re going to do’.

"Most councils would say this is where things got a bit difficult."

If you think Three Waters being taken out of councils’ hands means it will be funded by central government, it is, while a logical assumption, wrong.

Users will pay for Three Waters services, maintenance and upgrades, Voice B says.

"It will be paid for by water metres and water charges to individual people, which then get amalgamated and spent in the area that water entity looks after."

Voice A uses Auckland’s council-owned, independent, water services provider, Watercare, as an example of what is to come nationwide.

"While they’re owned by Auckland Council, they have an independent board that has a very clear statement of intent set by the council, but a clear accountability back to the customer.

Local government will not be able to deal with the problems of adaptation. The adaptation strategy that’s been adopted makes that clear. Funding is going to be a terrible problem.

"It’s more like a power utility or other infrastructure utility. You have a direct relationship with your customer; you charge them a price that covers your cost of operation and guarantees you a revenue stream that will enable you to do a long-term asset management plan. And you’re accountable back to the customer to deliver the service standard."

Voice B is doubly sure central government does not want to bear the cost.

They know an alternative was suggested to government; one based on the Waka Kotahi New Zealand Transport Agency model.

Waka Kotahi gets its revenue primarily from fuel taxes, road user charges and vehicle registration and licensing. It then funds local authorities to carry out agreed roading repairs and projects.

"But the feedback was that ministers said ‘You can’t just suddenly expect that we’re going to subsidise [water infrastructure]’."

What those ministers did not appreciate, Voice A says, is that it could have been funded by rates.

If local councils kept control of their Three Waters assets, they could siphon water rates they collected to the Waka Kotahi-like central agency, which could then ladle the cash out as councils committed to water infrastructure work.

That said, Voice B still finds it curious the Government is not funding Three Waters centrally.

"Rates are how you all do something locally, that matters locally — you all cross-subsidise each other locally. Taxes are how you do exactly the same thing at a national scale.

"But the interesting thing is, they didn’t want to use tax."

Despite the Government’s reluctance, the comments of those spoken to by The Weekend Mix suggest the financial implications of climate change for Three Waters will be so large that it will not be able to dodge stumping up some of the cost.

The recent Nelson floods are showing the "transformational change" that will be needed to deal with climate change, Voice C says.

"Local government will not be able to deal with the problems of adaptation. The adaptation strategy that’s been adopted makes that clear. Funding is going to be a terrible problem."

Voice A adds to that.

"The really big challenge is climate change and lifting environmental standards into the future.

"Most councils don’t have the balance sheets to cope with that. And ratepayers are not that fussed on paying. "It will be a responsibility of the new entities to make sure they meet climate change obligations, particularly in the area of stormwater, as we can clearly see in Nelson.

"Those obligations and costs are going to be significant."

Ultimately, perhaps, it makes little difference. No matter whether Three Waters is funded through rates, a utility company-style bill or a central government tax, everything eventually is paid for from citizens’ pockets.

The experienced voices have different views on whether Three Waters centralisation will result in a detrimental loss of local control.

Voice A says no.

"How important is local knowledge to running a series of water infrastructure assets, putting pipes in the ground and making sure they supply water?

"The water entities’ statutory obligations will require them to understand the needs of the local community and make sure it is provided.

"And making sure that happens will be an independent regulator, which is what we don’t have at the moment."

But Voice B believes it does matter.

"What a lot of councils will be worrying about is — if an outfit in Christchurch is running water for most of the South Island, how do you plan where new subdivisions go in Dunedin?

"For most parts of the country now, when it comes to greenfield developments or putting in intensive housing, the main impediment is the limitations on the water infrastructure. How do you manage that if the people making the decision are not even based in your town? "

The voices are of one mind rejecting the suggestion Three Waters is a government ploy to steal our infrastructure assets.

"Well, whose assets?" asks Voice C.

"They are the public’s. And the public is represented by central government and by local government."

Voice B says calling it theft is "bollocks". "It’s a bit of a beat up, because ratepayers and taxpayers are the same people."

"It’s not like we take personal ownership of these things," Voice A adds. "What we really need as individuals and consumers is high water-quality standards that meet environmental standards, and to know we’re making smart investment decisions.

"And that’s exactly what these entities are set up to do."

The final contentious question is co-governance. The voices’ range of views add to the picture.

Voice B believes co-governance was chosen, in part, to prevent the country’s Three Waters infrastructure being privatised.

"You can imagine the Labour Party setting up these entities, and then they become completely independently owned and run, and then they get sold to Australia — and it’s our water. Rather like the electricity companies did when they got set up as state owned enterprises."

But with co-governance, a sale would be unthinkable.

"There hasn’t been a lot of discussion of that in the press, but certainly when groups of politicians and chief executives get together there is an acknowledgement that that is a very easy way of making sure they’ll never get sold. Maori would never sell the water, because it’s taonga.

"I think that’s highly likely to have been at least one of the factors."

Voice A has reservations about the 50:50 ratio. But adds it will ensure both parties take equal responsibility for positive outcomes.

"With ownership, in inverted commas, comes responsibility . . . They will be in a governance position to make sure that the entities are delivering to the needs of the whole community."

Co-governance is not a new concept, Voice C says.

"We’ve got[co-governance of] the Waikato River, we’ve got the very innovative settlements in the Ureweras and the Whanganui River has legal personality.

"To make political, prejudicial statements and stir up feelings about it is not helpful."

Voice B concludes by bringing it back to what sparked the Three Waters reforms.

"Look, part of this centralisation is to try to stop local government, local councils, from having control. Because they’ve made decisions to keep rates down instead of doing the water work. And they’ve almost all done it.

"To be fair, many councils were just beginning to turn this around. Particularly post-Havelock . . .lots of councils were starting to say, ‘OK, we need to change the way we do this, we need to sort it’.

"But if you want to make sure that nobody can use water money to build a library ever again, then on that day-to-day basis it needs to be controlled by different people."