Oleg is speaking via video link from his office about a kilometre from the Sydney Opera House; talking about the ethics of where his rapidly expanding company’s cutting-edge counter-drone technology should, and should not, be sold.

The world’s nations are divided into three groups, the DroneShield chief executive says.

There is the white list - countries like the United States, the United Kingdom, New Zealand and France.

There is also the blacklist - players such as Russia, China, North Korea and Iran.

"You know, the usual fun crew," he says.

And there is the grey list, whose members change from time to time; countries not strictly beyond the pale, but with whom Oleg and his team choose not to do business.

"We're saying no, no. You’ve got to choose what side you're on. And if you're on the side of the good guys, you can't ship to anybody else."

For those not first-naming it with generals and ministers of defence, DroneShield is an unfamiliar moniker. Less than a decade ago, however, even the military brass who are now so aware of the capabilities of the Australian company’s drone-defeating weapons had never heard of it.

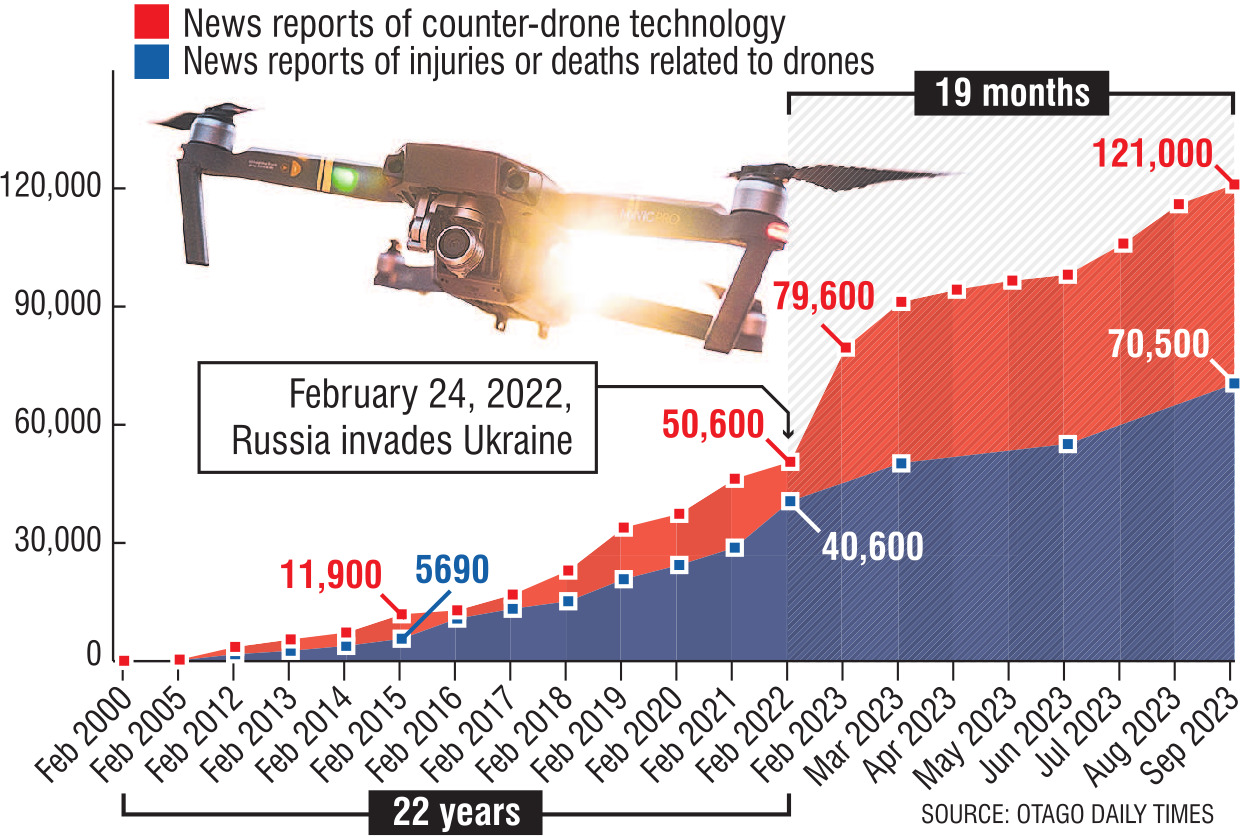

DroneShield began creating the counter-drone industry before most people had any idea drones - unmanned aerial devices remotely guided to scope out enemy forces, hack software, direct missile attacks and dive-bomb with explosive payloads - would become the global poster child of 21st-century conflict.

It was then, in the early-2010s, when quadcopters were still toys flying around living rooms, that two United States scientists foresaw their potential as a military threat. Using cutting-edge audio technology to detect the sound of an approaching drone, they tested their anti-drone prototype at the Boston Marathon just two years after a domestic terrorist attack killed three people and injured hundreds of other runners and spectators.

"The Wall Street Journal ran an article about this really unusual, innovative technology dealing with a threat nobody had thought about before," Oleg explains.

Investors saw an opportunity, bought a majority stake and soon realised a lot more money would be needed if DroneShield was to make the most of having pole position in this nascent market.

So, they gave Oleg a call.

At that point, he was an investment banker in Australia. But not a happy one.

"I felt I had overstayed my welcome.

"I just didn't enjoy writing pitch books and trying to present ideas to other people, for those people to decide and create something.

"You feel like you are on the stands watching gladiators, as opposed to being a gladiator yourself."

For his part, Oleg knew and trusted the investors and was taken with the "really cool technology".

"I thought this was ... something I could sink my teeth into ... that was also very much a blank sheet of paper where I could create something."

In 2015, at the age of 33, he became DroneShield’s CEO.

Oleg was born in Saratov, Russia. He was 9 when the Soviet Union became the Russian Federation. President Boris Yeltsin privatised state assets and deregulated the economy with little apparent forethought. It was a wild and dangerous time.

"I think my mum could read the writing on the wall ... and wanted a brighter future for me."

When Oleg was 15, he and his mother emigrated to New Zealand, settling in Christchurch.

It was 1997. That year, Yeltsin appointed former KGB agent Vladimir Putin as his deputy chief of presidential staff. The next year, Putin became head of Russia’s security and intelligence service. By the end of 1999, he was the country’s president.

"He promised to clean up all the criminality. Essentially, the government became gangster No1 and suppressed all the little gangsters."

In Russia, Oleg’s mother had been a doctor. In New Zealand, she could not work as an ear, nose and throat specialist and had to retrain as a naturopath.

He is grateful for her sacrifice.

"We basically had no money and ... lived in city council housing. The primary reason she moved was for my future."

New Zealanders, he says, were welcoming and accepting.

"I felt at home from day one. I was just a young guy with no English, no money and no understanding of the culture; just with ambition to get out of my situation and make something for myself one day."

In May of 2016, DroneShield listed on the ASX, raised $7 million - much of it from "mum and dad" investors - and used the funds to begin scaling the company and its technology.

Devices to detect drones naturally called for devices that could stop those drones in their tracks. The first drone gun was a 5kg "rifle" attached to a 10kg Ghostbuster-type backpack.

A promotional, online video garnered a million hits in its first week.

"YouTube approached DroneShield to start putting paid advertisements on what was our advertisement to start with, because it was such an unusual thing."

At first, the hardest job was convincing prospective customers they might need counter-drone (C-UAS) tools, Oleg recalls. But that objection evaporated as drones made increasingly frequent and disturbing appearances in security incidents, disputes and conflicts around the globe.

In 2018, DroneShield got its first multimillion-dollar order; $3m for equipment to protect Saudi oil fields from Houthi rebel drone attacks.

Research and development led to smarter, better technology.

"Radio frequency is by far the best way of detecting drones," Oleg says.

With it, a C-UAS operator can search for the radio wave "handshake" between a drone and its controller.

"So, we listen for those uplinks and downlinks and can tell, in real time, the location of both the drone and the pilot."

A drone gun can then fire a jamming signal, forcing the drone to land or crash.

Interest in DroneShield’s technology kept growing strongly. The company was doing business in about 100 countries, including New Zealand.

"We were asked to deliver the first batch of our counter-drone equipment right away, with support from a foreign government."

He has no love for Putin. The feeling, apparently, is mutual.

"Six months ago, I was personally put on the Russian government sanctions list, together with a couple of other people at DroneShield, off the back of our involvement supporting Ukraine."

The first batch of counter-drone devices sent to Ukraine had an immediate impact. DroneShield was quickly swamped with inquiries from the Ukraine armed forces, civilians and families of Ukrainian soldiers.

Oleg is reluctant to detail what DroneShield devices, in what quantities, through which countries’ support, are being used in the war.

"We obviously feel it's completely unacceptable that Russia has invaded.

"So, anything that we can do to assist and help Ukrainians to defend themselves and push back, you’ve got to do it.

"I'd like to think that we're a meaningful part of Ukraine's defence."

Business continues to boom.

In July, for example, a US government agency ordered $33thm worth of DroneShield counter-drone devices.

The company now employs close to 100 staff, most of them engineers.

"The invasion of Ukraine has highlighted that drones are the new future of warfare and that wars are still a thing that happen," Oleg says.

"A lot of militaries and intelligence communities around the world are beefing up purchases of drones and counter-drone equipment.

"There is this saying in the military, ‘You have to fight the next war, not the last war’."