One hour could have saved Western Samoa from being ravaged by influenza.

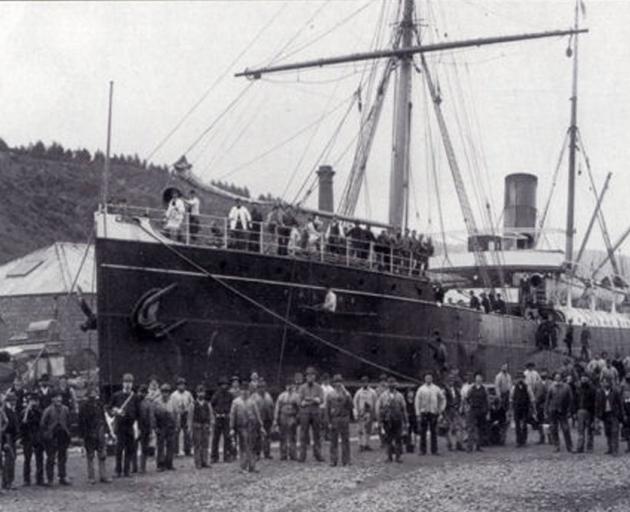

When SS Talune arrived in Apia on November 7, 1918, it had already had a stormy voyage.

Given a clean bill of health when leaving Auckland in October, upon arrival in Fiji on November 4 all passengers and crew were medically examined, and the ship was quarantined.

Suva officials were not being overly cautious: the 1918 influenza pandemic was sweeping its way south and the disease - eventually to kill 5% of the world's population - was not wanted.

Talune sailed to Levuka - and was again quarantined - before its fateful voyage to Western Samoa.

No entry was made in the ship's log of any illness aboard.

Upon arrival, no-one aboard said the ship had been quarantined, and no-one ashore seemingly thought to have a doctor examine the crew and passengers.

The subsequent Samoan Epidemic Commission was scathing.

''With a sufficient number of thermometers we venture to state that a ship, say, the size of the Talune, visiting these islands, could be medically examined in one hour - surely not a large price to pay for the additional safety which would be thereby obtained,'' it said.

Instead, Talune was granted pratique - permission to have dealings with a port.

''We are of the opinion,'' the commission report continued, ''that had the temperatures of all the passengers and crew been taken ... no qualified port official could have granted immediate pratique without being guilty of criminal carelessness.''

The consequences of that decision were catastrophic.

One passenger died the following day, another two days after leaving the ship, and the disease spread rapidly.

The population of Western Samoa on September 30, 1918 was 38,302 - by the end of the year it was 30,738.

Around 20% of the population died in just three months.

As the commission noted, the toll was probably greater: ''many people are even now suffering from the after-effects of the disease, while others are totally or partially incapacitated,'' it wrote in August 1919.

''It was devastating, and statistics suggest the final death toll may have been 23% of the population,'' University of Otago history professor Judy Bennett said.

''Every family would have suffered, and they soon learned what had happened in American Samoa, where there was a total quarantine and no-one got the flu.''

This happened under the watch of Colonel Robert Logan - a Scottish tenant farmer's son who found fortune in New Zealand, buying a Maniototo farm, Maritanga, in 1883.

With the advent of the Boer War, Logan discovered a passion for the military.

He founded the Maniototo Mounted Rifle Volunteers in 1900, and four years later joined the Otago Mounted Rifles.

By 1912 Logan was a temporary colonel in the regular army.

In 1914 Logan was appointed commander of New Zealand's first military adventure in World War 1 - the capture of Western Samoa, then a German colony.

With no opposition the islands were quickly captured, and Logan was named administrator.

''They liked to think they were pretty good administrators, but really they were rank amateurs,'' Prof Bennett said.

''These were military guys who did their best, they weren't bad people, but they weren't to know anything about how to run Samoa.''

Despite New Zealand crying out for soldiers to serve overseas, Logan - by now a full colonel - stayed in Samoa for the duration of the war.

''He [Logan] had been offered help by the Americans and he declined it,'' Prof Bennett said.

''Basic nursing could not be performed - many people died from the flu, but also from complications arising from pneumonia, because no-one was feeding them or keeping them warm.''

The inquiry report offered one chilling example of the impact influenza had: at Papauta Samoan Girls' School only one of the 104 pupils did not catch the disease.

Col Logan visited, and finding 70 abed and 30 convalescent, decided the latter were ''loafers'' - a conclusion the inquiry labelled ''hasty''.

Overall, it found no doubt Talune brought the disease to the islands, and that many measures could and should have been taken - both before and after the pandemic reached Samoa - which could have saved lives.

''There was no getting out of it, there were no excuses, so many mistakes were made,'' Prof Bennett said.

''You couldn't reach any other conclusion.''

Col Logan left Samoa in 1919 and to the end believed his administration had been a success,

''They will get over it (the pandemic) provided they are handled with care,'' he wrote to his successor.

''They will later on remember all that has been done for them in the previous four years.''

His optimism was ill-founded: Western Samoans resented New Zealand's role in the flu pandemic for decades - ''it is embedded in their memory to this day,'' Prof Bennett said.

In 2002 then New Zealand Prime Minister Helen Clark formally apologised for injustices arising from New Zealand's administration of Samoa in its earlier years, and expressed sorrow and regret for those injustices.