A cataclysmic decline in insects is taking place, virtually unnoticed. Bruce Munro talks to renowned entomologist Anthony Harris about love, loss and the impending Sixth Mass Extinction, which could wipe land-based life from the globe.

The email response from Anthony Harris is as distinctive, quietly direct and laden with meaning as the man himself.

Hi ... Could I discuss this later today or perhaps on Monday?

The sixth mass extinction worries me on a daily basis and has worsened steeply after about 1950.

I consequently would like to discuss this subject with you.

With thanks,

Tony

Three hours later, Harris, an award-winning New Zealand entomologist, is leading the way through an inconspicuous door at the back of Otago Museum's public toilets.

Surprisingly, it opens on to a long, silent, concrete corridor partitioned by a series of security-controlled doorways. Harris turns left through another swipe-card-entry door into a short hall and then right into a small, high-ceiling office, somewhere in the bowels of the museum.

The walls are lined high with books and boxes. The utilitarian desks ringing the room are equally burdened with papers, open books and display cases of beetles, wasps and other deceased members of the class Insecta.

This 3m-by-4m bunker is the repository of a lifetime of devoted research by Harris, one of New Zealand's leading authorities on creepy-crawlies.

A lifetime is no exaggeration.

He clearly remembers the first time he saw a beetle, aged 1.

It was a sublime, formative experience.

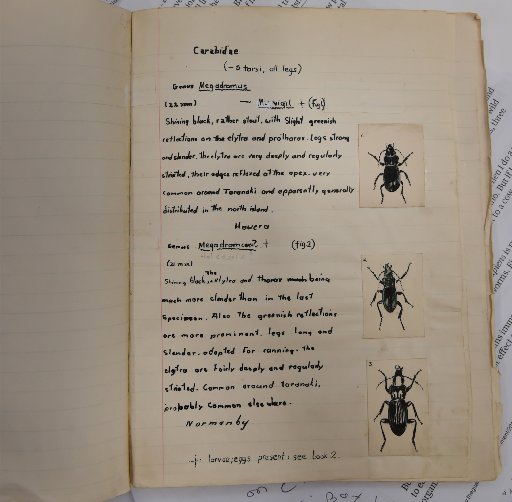

"Lifting up boards on our section in Hawera, Taranaki, I was amazed to see Carabidae ground beetles,'' Harris recalls.

"I immediately and passionately loved them for their shape, sculpturing and form; their shiny black iridescent bodies with elegantly sculptured wing cases and bright green iridescent sheen.''

At 5, he produced a small book on Hawera beetles; at 10 a neatly hand-written and beautifully hand-illustrated book on New Zealand beetles.

After winning the British Commonwealth Research Competition at 18 and gaining first class honours in zoology, at Victoria University, Wellington, Harris began a more than 40-year career at Otago Museum, collecting, studying and describing New Zealand's insect species. His particular specialty became New Zealand's spider-hunting wasps and the other families of solitary hunting wasps.

"I was motivated by an intense, lifelong, emotional love of insects and also for the rest of nature, including plants, and the wild, natural landscape,'' he says.

For the past 18 years, he has worked simply for love, unpaid, as the museum's honorary curator of entomology.

In 1995, he was awarded a Science and Technology Medal by the Royal Society of New Zealand.

To date, he has published 150 scientific papers (the most recent, last year) and has written more than 1570 weekly, natural history articles for the Otago Daily Times.

Out of respect, fellow entomologists have named three species after him; a butterfly, a stiletto fly and a solitary wasp.

"Personally, I believe a true entomologist has a passionate love of the subject and must like insects more than anything else.''

In stark contrast, most of us ignore, swat or poison insects.

We desperately need educating, Harris says.

He starts at the beginning, with a black and white photocopy of a pie chart representing the animal kingdom and its various, speciated slices of pie.

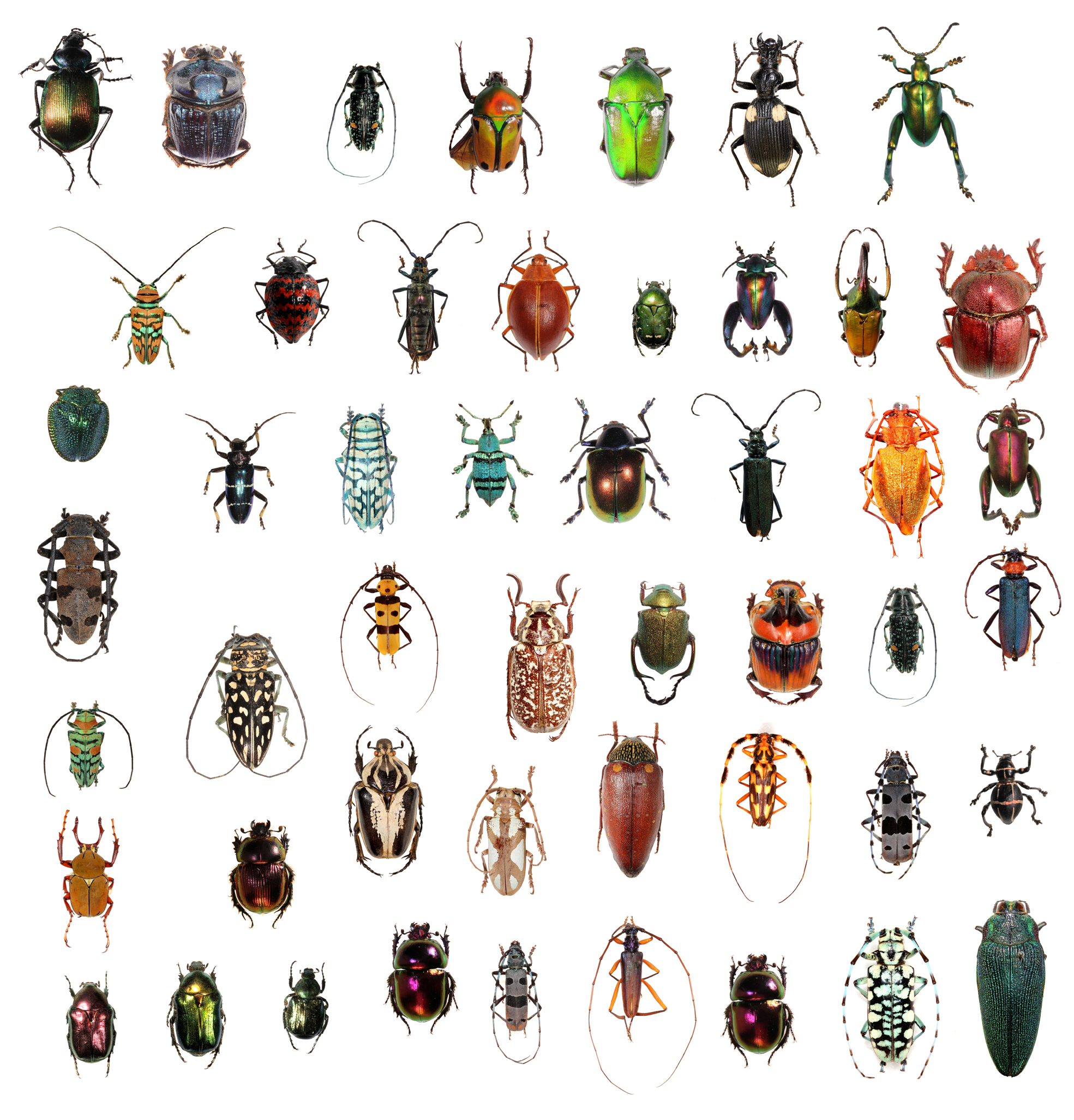

Eighty percent of all known species of animals are insects, he says.

You can tell an insect - if you can get it to hold still for long enough - by its six legs, exoskeleton divided into a head, thorax and abdomen and its two waggling antennae.

By far the biggest orders of insects are the coleoptera (beetles) and the hymenoptera (wasps, bees and ants), followed by the lepidoptera (butterflies and moths), then diptera (flies and mosquitoes) and, finally, other insects, such as grasshoppers and silverfish.

"The total number of individual insects alive worldwide today is ...''

He writes it out. 10,000,000,000,000,000,000.

"... 10 quintillion. That equals more than 1500 million insects for every person.''

There are insects that spend part of their lives under water. Quite a few can walk on water.

Some communicate with chemicals. Others, with sound and light.

Insects grow by shedding their older, smaller, exoskeletons. Some completely transform. The landlubbing caterpillar, for instance, wraps itself in a chrysalis, melts itself down and rebuilds to emerge as a delicate, winged creature.

NEW ZEALAND does not have many butterfly species and only about 46, mostly introduced, ant species, Harris says.

In our long-isolated land, giant weta took the role played elsewhere by mice; until rodents arrived and virtually wiped them out.

Beetles are well represented in Aotearoa. Of weevils alone, we have about 2000 species, he says.

As native insects, we have only solitary bees and wasps.

"Bees are basically wasps that are vegetarian.''

Harris' research showed that in some species of New Zealand solitary wasps the males mimic the females, pretending they too can sting.

"There is a lot of this mimicry in the insect world,'' he says, rattling off some local examples.

There are two species of fly that mimic a wasp right down to its coloured markings and the way it flies.

Some of this copy-cat behaviour is downright nasty - or ingenious, depending on whether you are predator or prey.

There's the robber fly, for example, that imitates the look and walk of a female wasp.

"The male wasp flies down to say hello and the robber fly responds by jumping on the male and eating it.''

Entomologists are constantly discovering more about insects and the important role they play in the global ecosystem. But there is so much more to learn, Harris says.

New Zealand's 10,000 known insect species are probably less than half of the real number.

This week it was revealed that last summer, on mudflats near the mouth of Otago Harbour, Assoc Prof Steve Kerr found a previously unknown species of native fly, now labelled Scorpiurus aramoana.

Ninety percent of New Zealand's insects are found nowhere else.

Worldwide, about one million insect species have been identified, but scientists estimate there are another 29 million without names.

That is a fair bit of work left to do.

Except they are disappearing quicker than entomologists can record them. Bees and their decline have been worried over for more than three decades.

The dwindling numbers of other insects, however, is not widely recognised nor talked about. Only now is it becoming so obvious to some observers that the conversation is beginning to buzz.

In 2016, United Kingdom (UK) environmental journalist Mike McCarthy wrote The Moth Snowstorm: Nature and Joy, about the disappearance of moths.

Last year, retired MP and former environment minister Marian Hobbs, speaking at the Orokonui Ecosanctuary, made a similar observation about moths in New Zealand.

"I remember driving when I was in my 20s and 30s,'' Hobbs recalls.

"I used to do a regular trip from Dunedin to Christchurch. You would have to clean off the windscreen, and the radiator grille, because it would be chocker with insects.

"Now, I still drive quite a bit, and you don't get anywhere near as much.''

SCIENTISTS are wading in with troubling findings of their own.

Twenty years ago, one billion monarch butterflies made the annual migration from Canada to Mexico. Entomologists say the latest count is 56.5 million, less than 1% of new-millennium numbers.

In October, last year, researchers revealed that, since 1989, three-quarters of all flying insects had disappeared from nature reserves throughout Germany.

The findings prompted warnings of an impending "ecological armageddon''.

Harris has noticed it too. He can recite a list of Latin-sounding native invertebrates that are now rarely, or never, seen.

During the 1970s, he was fossicking in a patch of bush on the edge of the Waipoua kauri forest, in Northland, looking for solitary wasps. What he spotted instead was "a distinctive carabid beetle with a very long, thin head and rounded pro-thorax''.

The interesting insect was a Maoripamborus fairburni.

"I knew it from [entomologist] Albert Brookes' 19th-century description of it. It was fairly uncommon then. But I haven't been able to find one since. might have been the last person to see one alive. There's quite a few like that.''

And humans, it appears, are the problem.

Harris waves a sheaf of pages. It is a new piece of research, published less than a month ago in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America.

Burdened with the deceptively boring title The Biomass Distribution on Earth, the paper, by researchers at the Weizmann Institute of Science, Israel, is in fact a ground-breaking assessment of all life on earth. It reveals the astonishing and disproportionate impact humans are having on the planet.

The total biomass, that is the total weight of all organisms on earth, is estimated at 545.2 Gt C (gigatons of carbon), the researchers say.

More than 80% of this, 452.5Gt C, is plants. Next comes bacteria (16%, 87.2Gt C) and fungi (2%, 10.9 Gt C). Animals make up just 0.4% of the total biomass. The globe's 7.6 billion people account for just 0.01% of all living things.

And yet our impact on the globe has been enormous - some would say catastrophic.

According to the Proceedings article, humans are responsible for the possibly irreparable loss of large chunks of the animal and plant kingdoms; more than 80% of all wild animals and half of all plants.

Anthony Harris finds it deeply disturbing.

"Farmed poultry now makes up 70% of all birds on the planet, with just 30% wild,'' he says with a shocked tone.

"The picture for mammals is worse. Sixty percent of all mammals on earth are livestock, mostly cattle and pigs, 36% are humans and just 4% of all mammals are wild.''

It is no wonder insects are dying out, he says.

Industrialised farming is one of the main causes.

McCarthy, who noted the decline of moths, writing in October about the dramatic drop in flying insects numbers in Germany, stated, "It seems indisputable: it is us''.

"It is human activity - more specifically, three generations of industrialised farming with a vast tide of poisons pouring over the land year after year after year, since the end of the second world war.

"This is the true price of pesticide-based agriculture, which society has for so long blithely accepted.''

Harris has no shortage of other ways humans are doing the dirty on insects: introduced pests, habitat destruction, clearance of forests and native vegetation, greenhouse gas emissions ...

And the various impacts are having a grave, multiplying effect.

When global climate changed in the past, insects, along with other animals and plants, could transition higher or lower and further north or south to areas where they could still survive.

Now, however, with so much deforestation and as temperatures climb, pockets of native bush and their entourage of insects have become life rafts slowly sinking in an uncrossable ocean of pasture land.

Just why the decline of insects is such a catastrophe is perhaps not immediately obvious.

Here's why, Harris says. They do everything from cleaning up waste to keeping plants alive and feeding us and the animals.

A study in New York city revealed urban insects get rid of thousands of kilograms of food waste each year. It adds up to less rotting garbage, recycled waste and fewer disease-bearing vermin.

Insects form the base of many thousands of food chains. Research has shown their disappearance is the main reason the number of farmland birds in the UK has more than halved during the past 50 years. No wonder, when it takes 200,000 insects to raise a swallow chick to adulthood.

Insects also take a lead role in pollinating flowering plants. About 70% of the human diet comes from flowering plants, which include the staples of most diets worldwide; wheat, corn and rice.

Insects keep the global ecosystem rolling down the highway of life.

They may be less the canary in the global mine and more the linchpin that is falling out of the world's axle and will cause the whole bus, with everybody and everything aboard, to suddenly lurch and crash in a spray of sparks and a cacophony of metal grinding on chip seal.

Without insects, we face total ecological collapse and global famine. It is being called the Sixth Mass Extinction. The Fifth Mass Extinction was the one that killed off the dinosaurs, 66 million years ago.

Harvard entomologist Prof E.O. Wilson has estimated that, without insects and other land-based invertebrates, humanity would only last a few months. Land-based plants and animals would be next to go. The planet would fall quiet and still.

The last time the earth was like that was 440 million years ago.

What should be done and what can be done is a matter of debate.

It is not helped by not knowing the extent of the problem.

Dr Greg Holwell is president of the Entomological Society of New Zealand.

All entomologists are concerned about global declines in insect diversity, Dr Holwell says.

"In New Zealand, although there are a number of excellent scientists researching the causes of insect declines and potential solutions, research funding is desperately needed to identify the specific causes and identify how we can manage the situation here,'' he says.

Harris' solution requires a radical paradigm shift.

Humans have to realise they are just one part of a bigger whole, he says with quiet, fierce, resolve.

"I think humans are just another species of carnivore ... They have to fit in with the other animals and plants, which are literally their relatives.

"We share a lot of the same genes. A banana has about 60% the same genes as a human.

"It has to be a form of symbiosis, with all the species of the same intrinsic worth. Humans are not of greater value.''

"We must value the other species, on whom we depend for our existence, very much more than we do at present and this should be reflected in our laws, spirituality and culture.''

From that point of view, preventing the extinction of insects is not merely, or even primarily, for the sake of saving humans.

"[Insects] are such a huge part of the fauna that if you take them out you destroy the food webs. But for me, it is the intrinsic beauty of insects that is the main thing.''

His views are echoed by Dunedin bone artist Bruce Mahalski.

Mahalski and Auckland-based medical doctor Craig Hilton have recently published a photographic book of Mahalski's art, Seeds of Life.

He uses his art, which mixes animal and human bone, to convey that "animals and humans, we're all in this together''.

"I do it to try to put us back into the natural order of things before it's too late.

"Craig and I both feel that humanity is on the verge of precipitating a massive extinction event and that it is the responsibility of both artists and scientists to wake people up.''

Seated in his office, holding a small display case of endangered and extinct native weevils, Harris recalls his second earliest significant memory of insects.

"When I was three, I used to keep beetles in tins,'' he says, gazing at an unseen, long gone, yet vivid scene.

"My brother, who was 1 year old at the time, put his hand in the tin and got bitten.

"He started crying and my father came out, tipped the beetles on the path and squashed them.

"It made me cry in anguish for a long time. I can remember it very clearly.''

Do his eyes moisten again?

If they do, it is not for himself, or for the possible fate of humanity, but for the loss of insects, the obliteration of beauty.