Tāme Iti featured in a recent report on TVNZ’s Te Karere news programme, climbing his mauna tīpuna (ancestral mountain) Taiarahia to mark 40 years since a protest he led to save its forest cloak.

He’s the silver-haired koro at the head of a group comprised of at least three generations. With them is a film crew, making a documentary about the struggle all those years ago, one of many Iti has led or joined in his seven decades on the planet. The hoariri, the enemy, then was pine trees — the threat of the land being lost under an exotic plantation. It wasn’t.

There’s mana in the moment, the people on their mauna, its regenerating bush preserved in perpetuity. Iti’s mana is assured, but it is there in the young Tūhoe faces too, sharing their thoughts with the Te Karere crew in the iwi’s distinctive mita (dialect).

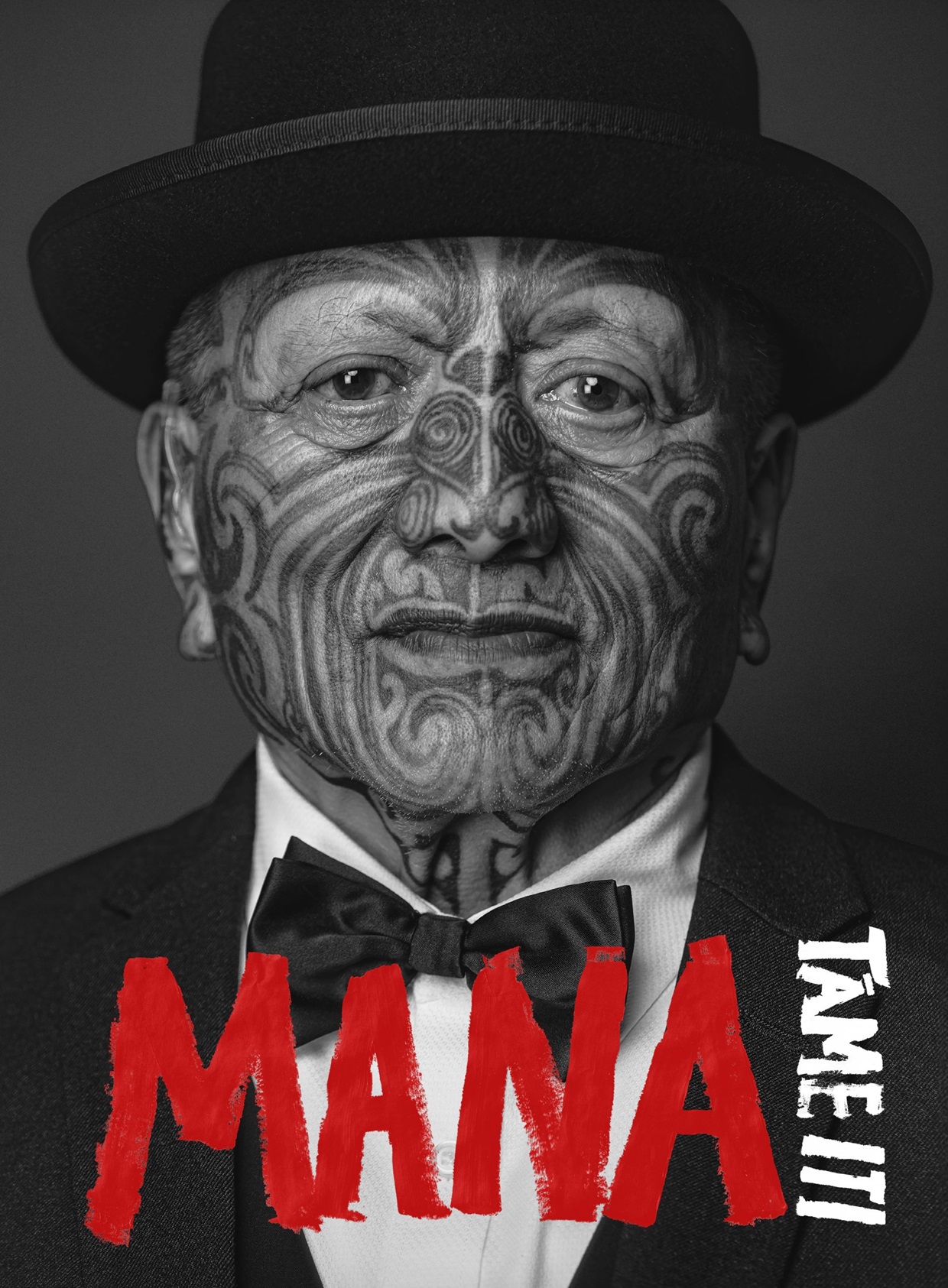

Iti speaks of both these things in his new book, Mana. Those long years of protest, when he struggled to keep the cause of ngā hapū Māori, of iwi Māori, of mana motuhake alive, but also of this new generation who don’t need to feel the mamae, the hurt, that he did. Because of the efforts of his generation.

Down the phone line from Whakatāne, where he is preparing for the book launch at the town’s new culture hub Ātea, Iti is content that the years have confirmed the stand he took to save the forest.

"It kind of brings us together that people are starting to understand more about our environment, our pūtaiao (science), you know? And they're finally saying, ‘whuu, he tika kē hoki tō kōrero e Tāme, koutou o ngā tamariki o te kohu’ (your talk was absolutely right, Tāme, you and the Children of the Mist, Ngāi Tūhoe)."

It’s the legacy of the taniwha hikuroa, one who has led by example.

"I see into the eyes of my mokopuna," he writes in Mana. "And I smile ... Kua puāwai ngā hua, ngā putiputi (the fruits and flowers have blossomed). I can see it now."

"He rerekē noa atu ō rātou wairua". Their spirit is completely different.

Mana is Iti’s story of the journey to restore mana, that elusive quality that defies easy translation — for himself, his hapū and ngā iwi Māori whānui, Māori more broadly.

It’s the story of a Tūhoe boy with te reo Māori as his first language who was told not to speak it at school, who grew up looking at the whenua whānako, the stolen land on the other side of the confiscation line that runs through Tūhoe country. Of the young man sent off to Christchurch in the late 1960s to get himself a trade in the Pākehā world, as a painter and decorator — but who made it home. Home to Tūhoe and his Tūhoetana.

Along the way there was that protest camp on Taiarahia. And there was also the protest for his river, Ōhinemataroa.

That was a few years later. At the time, jet boat races were roaring along its length.

"Awa are not just bodies of water — they’re part of who we are, they’re our tīpuna. Ko ahau te awa, ko te awa ko ahau," he writes: I am the river and the river is me.

"Yet with a splash and a roar, we were being sidelined in our own space."

The mana of the river needed to be upheld and restored.

So, Iti waded in. Literally. And stood there, waiting for the jet boats to power around the corner. Where he was standing, in a narrow section of the river, there was only room for one of them.

"I always look at it as a performance. It's theatre," he says of his activism. "You have to take yourself to that space and become a breathing exercise. Hā ki roto, hā ki waho. (Breathe in, breathe out.)

"And you put yourself there. And it can be quite challenging. It can be quite hard.

"Not everybody is ready to kill another person just like that, you know. So I had to take that risk. I might die on that, eh, but, you know ..."

In the event, the jet boat chose to crash through the willows at the side of the river, rather than through Iti. And the race organisers finally agreed to discuss their race route with him.

"I'm quite passionate about some of these things, you know," Iti says, possibly the most redundant statement ever made.

There’s mischief too, to go with the passion.

"You've got to smile, you've got to laugh, and it's quite exciting," he admits. "There's a moment of excitement, but there's also a moment of, holy hell, you know. And you go through that, holy hell, this fella's going to come and kill me."

You have to believe in what you are doing, he says. "Kei te pono ahau (I believe)," he says.

Iti seems always to have believed, or at least to have been possessed of a restless curiosity from which he built belief.

Back when he was setting out on life’s journey, everything was still to do. As a founding member of Ngā Tamatoa, alongside the likes of Syd Jackson, Hone Harawira, Donna Awatere Huata and Hana Te Hemara, he was part of a movement that exploded out of the 1970s, helping to reshape the country.

Already during his time training in Christchurch he’d been schooling himself in the politics of the street, hanging out around the speakers in Cathedral Square, mixing with communists, activists and poets.

Ngā Tamatoa were inspired by rights movements offshore, in the US but also the struggles of Australia’s Aboriginals. In Australia, a tent embassy had been erected in Canberra. It was 1972, election year here, and Iti decided Wellington could do with the same medicine.

So, he borrowed his father’s tent and pitched up on the Parliament lawn. Just him.

Again, Iti sees it as performance.

"Yeah, well, life is theatrical. People don't realise."

Every day we make decisions about how we’ll present ourselves to the world, he says.

"Shall I have black shoes or red shoes? Shall I wear a hat? So, life is very theatrical, and we do that every day.

"I discovered that performing arts is a way that we can articulate how we’re thinking, how to confront ourselves around these issues and create a space."

That space lies along a thin line dividing Tūmatauenga and Rongo, the gods of war and peace, and draws on the mortal and divine that reside in whakapapa, he says.

"Kei roto au i tāku puna ira tānata, kei roto i tāku ira atua," he says. (Inside me there is the wellspring of both the mortal and the divine.)

"I’m very much a total practitioner of that. And to do that, there’s a real fine line there."

The earliest stories are a touchstone for Iti.

"We have to look back to our nehenehe rā, our ancient times, to find guidance. In the beginning when Papatūānuku and Ranginui were together, it only took one of the kids to see the light out there and tell the others. That started a kōrero ..." he writes in Mana.

The past is in front of us, he says. We know because we keep bumping into it.

It was that phenomenon, of bumping into our past again and again, that Ngā Tamatoa and others were confronting back in 1970s New Zealand. Specifically, the huge loss of land Māori had suffered — that whenua whānako, the stolen land.

In the popular remembering, Dame Whina Cooper is the central figure of the 1975 land march, but as Iti writes in Mana, it was Ngā Tamatoa who initiated the action and recruited Dame Whina to lead it.

"We didn’t have the profile, and we knew that," he says. "Myself, Syd Jackson, all that. We didn’t have the profile, but we needed a profile."

So, they got around a table and drew up a shortlist.

"We placed a whole lot of names on the table, mainly males, and mainly from Ngāpuhi, and then there was one woman in that space, and that happened to be Whina Cooper."

She had been president of the Māori Women’s Welfare League and was already known as Te Whaea o te Motu, Mother of the Nation.

"Koirā te kanohi. That’s the face. And then we needed a slogan," Iti recalls. "Not one more acre of land. That came from us, from us, a young generation."

There’s a lot going on in Mana — Iti’s life of activism could fill volumes. And he concedes his book is just a snapshot. But it’s his own framing.

"I’ve been trying to put something together for 20-odd years, you know," he says. "I finally got my head around it, you know, and I’m telling my own story, and not somebody else writing a story about me.

"I’m in my 70s, you know. And so I think it’s just really important that we capture those moments, capture those moments and share those whakaaro, you know, whakaputa i ngā whakaaro (publish those thoughts)."

It’s an opportunity to set a few stories straight, what was really going on when he shot that flag in front of the Waitangi Tribunal at Ruatoki, and who really stole Colin McCahon’s Urewera mural — a question long speculated upon but never settled, until now.

Well, it wasn’t Iti, but it was his idea. And it was Iti who, after long conversations with arts patron Jenny Gibb, arranged for its return.

Iti writes about standing in front of the painting in the Āniwaniwa Visitor Centre, at Lake Waikaremoana.

"A thought came into my head: ‘I want this painting to disappear. I want it to vanish’. My whakaaro was that I could use the painting to make a statement: the Crown stole our land, whenua whānako, so maybe if they lose this painting, they will feel a tiny fraction of what it’s like to lose something precious. I wanted them to think: ‘This is how it feels to have a taonga tuku iho taken from me’."

It was a success too, he writes.

"For me, the McCahon painting activation was hardcore, sure. The logistics and the strategy were stressful. But it worked. People talked about what mattered to us."

In 2007, the Tūhoe raids put him on the front page. It could all have been avoided if the police had just come and talked to him, he writes. The camps he was running in Te Urewera were a threat to no-one.

It hasn’t been easy to move past the trauma of the raid on his house, its spotlights, guns and dogs.

"You see red dots on your chest and all of that, and you’re going, holy hell."

He talks through it still with the people around him, he says.

"And you say, tino waimarie tātou, e hoa mā. Kei konei tonu tātou. Kei te ora tonu ahakoa he aha pēhea."

("We’re very lucky, my friends. We’re still here. We’re still alive, despite everything.")

In the end he had to let it go.

"I couldn’t hold on to it, you know? I had to let it go. I had to let that experience go and, again, then I can paint about those things."

One of the things he writes about in Mana in connection to the raids is the day the police returned to apologise, Police Commissioner Mike Bush bringing some biscuits with him for the occasion.

"To the credit of the police, they followed Tūhoe tikanga to restore their mana and cleared a way forward. For me it showed that the restoration of an offender’s mana is intrinsically linked to the restoration of the victim’s mana. That is justice."

Building back mana has been a life’s work for Iti.

"It’s like a jigsaw puzzle, trying to put it back together," he says.

Piece by piece, manifesting this concept, this idea, in his communities. Living it.

"Well, you know, you’re going to see it, you’re going to feel it, you’re going to eat it, taste it, you know, and it becomes a colour too, and sometimes it becomes blue, sometimes it’s got a bit of red in it," he says.

"It’s actually trying to make sense of it, you know, and then I finally got it," he says.

"Mana motuhake for me is my mana motuhake, my liberation, you know. And in order for me to be able to articulate mana in that shape or form, I had to feel it, then I get it.

"It took me 60 to 70 years to reach that point, and here we are, you know? It’s like painting a picture, you know?

"And people would say, ‘how long did it take you to do that?’. It doesn’t really matter how long, it’s a period of time, you know?"

In that context, Iti has been thinking about Wiremu Tāmihana Tarapīpipi Te Waharoa, a central figure in the establishment of the Kingitanga, whose initiative, it seems to Iti, is now bearing the long promised fruit — after all this time. That was clear to him at the recent Koroneihana at Ngāruawāhia, at which the Māori queen Nga wai hono i te po stepped out of a year’s mourning for her father to greet huge crowds of well wishers, poi in hand.

The occasion involved a kawe mate, remembering the departed, but was also a celebration of that new generation who don’t carry the mamae and an invocation of the same mana motuhake Iti writes of in his book.

"I’ve been going to the Koroneihana since 1972," Iti says.

But this time, Tarapīpipi’s vision all made sense.

"I got it, I got it, what Wiremu Tāmihana was trying to get at."

As usual, it doesn’t end there for Iti. He’s taken that experience back to Tūhoe.

"Me aha tātou? (What shall we do?). What’s that look like for Tūhoe, for the next generation? And, you know ... having those little conversations. So, yeah, yeah," he says, apparently as excited as ever by the possibilities for art and activism.

"I’m just going to live to the day I die, you know. There’s no room for retirement. It doesn’t exist."

In conversation

• Mana: In Conversation with Tāme Iti, Dunedin Writers and Readers Festival, Dunedin Town Hall Fullwood Room, today 5.30pm.

Tāme Iti will be in conversation with Paulette Tamati Elliffe and Komene Cassidy.