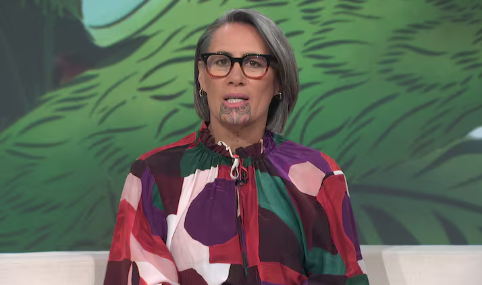

They knew what a moko was, and also a moko kauae; they had seen whānau and other wāhine adorned with it.

For a moment, there was silence in the car. Then one of my children spoke u, "are you sure, Mum? Having a tattoo on your face is pretty extreme".

That comment caught me off guard. It wasn’t said with judgement, but it landed with a sting. That sting came from a feeling that somehow, as a māmā, I’d failed to share the depth and beauty of this taonga tuku iho. That sting came because she saw moko kauae as a tattoo, not as whakapapa.

And that revealed just how deeply colonial ideas still linger, even within my own home.

Before I could respond, my youngest, the only one who had attended kōhanga and now kura kaupapa, chimed in with absolute confidence, "I love it, Mum! Can I get one too?".

That small exchange has stayed with me. I later asked the same child if she remembered the conversation, she didn’t. But I had carried it with me. Her words had sparked something that has only grown stronger since. For some time, the desire to reveal my own kauae has been quietly building within me. At first, it was a whisper, a thought I tucked away.

Then others began to see it for me before I could say it aloud. Over time, the feeling became more insistent, less like a decision and more like a remembering, as if my tūpuna had seen it, as if my skin already knows what it is meant to carry.

There’s a belief that every wahine Māori already has her moko kauae; she just hasn’t revealed herself yet.

Over the past year, I’ve been listening and learning. I interviewed six wāhine from my own marae, asking about their "why" and their experiences of living with moko kauae in their everyday lives. Some spoke of personal healing after loss, others of timing, when it simply felt right, some doing it so their tamariki and mokopuna could see a proud wahine Māori every day.

Their stories haven’t just informed me; they have shaped me, clearing the path toward my own mokopapa.

The story of moko kauae is also the story of suppression. For generations, wāhine were told to hide their culture, their reo, their bodies. The art of moko was condemned and many of our nannies carried shame where once there had only been pride.

That loss was not just about appearance, it was about identity. So, when I say some of the wāhine spoke of personal healing, that includes healing from the loss of culture, of language, of self-worth, of belonging. The trauma passed from generation to generation still echoes. For many, reclaiming moko kauae is a way to reclaim all that was taken, to restore mana motuhake, rangatiratanga, and wahinetanga. Yet among many wāhine Māori, I’ve also heard this quiet question: Am I worthy?

It’s whispered by those who don’t speak fluent reo, who live away from their marae, who feel they haven’t "done enough" for their iwi. This idea that there is a list of criteria to prove worthiness before revealing moko kauae, is, in itself, a colonial shadow. Moko kauae is not about status. It’s about whakapapa, commitment, and aroha ... and if your intention comes from a place of truth, respect, and love, that is enough. That is always enough.

When a wahine Māori walks into a boardroom, a classroom, or a supermarket with moko kauae, she sometimes unsettles assumptions of what leadership, professionalism, or beauty should look like. She makes visible what has too often been pushed aside, been misinterpreted, been judged and been devalued. That visibility can spark discomfort, but it can also spark transformation. We are seeing moko kauae more and more these days, in classrooms, on stages, in Parliament, on television, in our neighbourhoods.

Every time tamariki see those wāhine in all spaces, it’s normalisation is in motion. We are telling them, without words, that moko kauae will not hold you back. That you can be anything, go anywhere, and carry your whakapapa proudly on your face.

I often think about what Aotearoa would look like if every wahine Māori felt safe, supported, and celebrated in wearing her moko kauae.

What if our tamariki grew up surrounded not by whispers or sideways glances, but by open admiration and respect?

My daughter’s question, "are you sure, Mum?" has become my motivation. Yes, I am sure. I am sure because I want my children to grow up in an Aotearoa where moko kauae is not seen as "extreme", but as extraordinary.

And when my youngest responded, I smiled with a quiet sense of pride. A sense of pride and belief that for her generation, moko kauae won’t need to be explained or defended. It will simply be celebrated.

He puna moko, he mokopuna