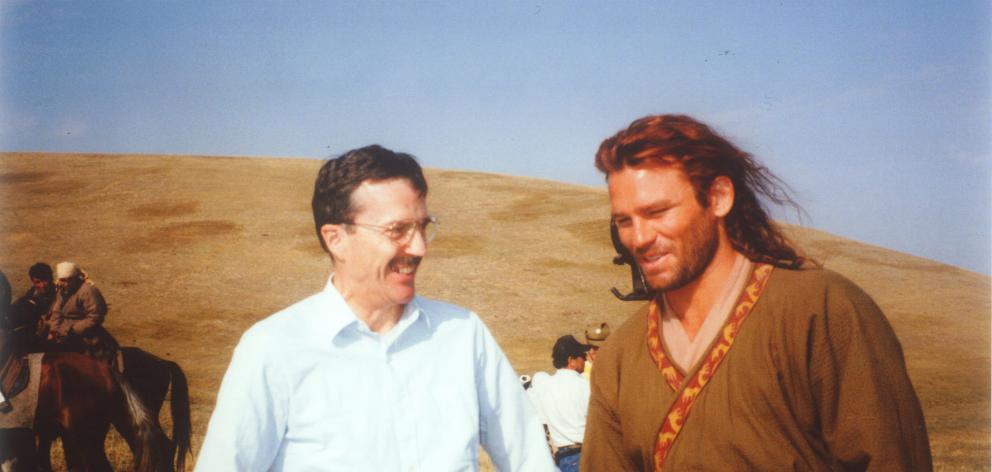

Dunedin-born diplomat Gerald McGhie has had a front-row seat to some of the 20th century’s most historic events, writes Shane Gilchrist.

Gerald McGhie has travelled from the jungles of Papua New Guinea to the great halls of global power; from Russia’s eastern outposts to Manhattan’s clogged streets; from Samoan villages to Seoul subways. He has seen, first-hand, a United States president impeached and a communist empire fall. It’s been quite a career.

In a remarkable twist of timing, McGhie boasts the honour of being New Zealand’s last ambassador to the Soviet Union, as well as its first to Russia.

His almost 40-year career as a diplomat included two postings to Moscow. The first was from 1979 to 1982 (as New Zealand embassy counsellor and charge d’affaires); the final stanza of Communist Party leader Leonid Brezhnev’s 18 years in office, it included dealing with the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, as well as the West’s subsequent boycotting of the 1980 Moscow Olympics.

The second spell, from 1990 to 1993, was even more dramatic: having survived an August 1991 coup attempt, Soviet President Mikhail Gorbachev announced his resignation on Christmas Day, signalling the collapse of the USSR and the rise to power of Boris Yeltsin.

"The breakup of the Soviet Union was the second-most significant event of the 20th century [behind World War 2] in my view," McGhie reflects via phone from his Wellington home as he ranges over subjects both past and present, many of which feature in his recently published memoir, Balancing Acts: Reflections of a New Zealand Diplomat.

McGhie officially retired in 2003, stepping down as director of the New Zealand Institute of International Affairs. He then briefly served as executive director of the newly formed Pacific Cooperation Foundation, before taking up a voluntary post with the New Zealand chapter of Transparency International, the global anti-corruption organisation, a role that continued beyond the 2008 Global Financial Crisis.

He may have stepped back from diplomacy, yet his interest in the sphere remains undiminished. He has maintained an academic approach to foreign affairs through the publication of journal articles, and has been a keynote speaker at the University of Otago’s Foreign Policy School.

Certainly, Balancing Acts conveys a deeply held passion - and concern - for foreign affairs.

"When I retired, a couple of publishers asked me if I would write my memoirs. However, I told them I was in no shape to write a book at that stage. I’d been in foreign affairs for almost 40 years so I was part of the culture.

"Still, when I became director of International Affairs I realised when I was addressing people that they sparked up when I drew from personal experience."

Let’s put it another way. McGhie’s book is a treasure trove of historic events, fascinating insights into cultures, and journeys to places both strange and significant. A quick list (in no particular order): Papua New Guinea, Samoa, Hong Kong, the Solomon Islands, South Korea, Zimbabwe, Canada, the Soviet Union ... Appointed New Zealand’s Consul to the United States, McGhie arrived in New York in 1972 as President Richard Nixon was about to be impeached.

"I landed as Watergate broke. Each night we would get hour after hour of the Senate’s investigation. Initially, we thought, ‘ho-hum’, but then I talked to a friend in the State Department and he told me to watch, that it was beginning to log-roll. And it did."

This brings us, inevitably, to the subject of US President Donald Trump. More specifically, the calls for his impeachment following disclosures he pressured FBI Director James Comey (whom he recently fired) to drop an investigation into Michael Flynn, the former national security adviser linked to alleged Russian interference in the 2016 US election.

"By surrounding Trump, by making him seem embattled, the very establishment against which some people voted [makes itself a target]," McGhie says.

"I’d suggest backing away from him. If the evidence is there, it will come out. If not, leave him alone. The situation is a mess."

Balancing Acts, which went to press shortly after the inauguration of Trump, does raise questions about the geopolitical ramifications of his presidency.

"In the climate of uncertainty surrounding Trump’s assertion of power, countries are scrambling to gain some understanding of the new administration’s policies. The best we can do in the meantime is look for signposts," McGhie writes.

"In his inaugural address, President Trump said that his policies would now project ‘America First’. Every decision on trade, immigration, taxes and foreign affairs will be for the benefit of American workers and families."

The essence of these comments is, in fact, vintage Trump, McGhie points out. They go back to 1978 when Trump paid to publish an open letter to The New York Times under the headline, "There’s Nothing Wrong With America’s Foreign Defense Policy that a Little Backbone Can’t Cure".

"The contents contained an early expression of his mercantilist economic views, a reflection of allies and alliances, and a conviction that the world economy is rigged against the United States ..." McGhie writes.

"As a recent commentator perceptively observed, Trump’s core views don’t align with any of the current approaches to foreign policy. Instead their close relatives are to be found in the America First movement of the 1940s."

Given the US is New Zealand’s third-largest individual trading partner - it accounts for almost $6 billion in annual exports, is a significant source of foreign investment, innovation and research as well as tourism - changes of policy there have significant flow-on effects, McGhie says.

"The US is an exceedingly difficult scenario for New Zealand, which has a government that sees the United States and Australia as coming first. We then look to Asia, where we have export markets, and Europe, where we also sell a lot of product ... we also see ourselves as a Pacific nation."

His point is: New Zealand needs its diplomats to continue putting it on the global political (and thus economic) map.

"The key job is to raise awareness of New Zealand. To do that, we need staff on the ground. Diplomats often provide commentary from a great deal of experience.

"As a professional diplomat you report and give advice to the best objective standards you have. Diplomats are part of a group getting our thoughts across to the Government. And the best ministers call you in to have a chat."

BORN in Dunedin in 1939, McGhie recalls his interest in international affairs began while at Otago Boys’ High School, where teacher W. G. ("Monty") McClymont, a former All Black, mountaineer and historian, offered inspiration via a seemingly endless stream of anecdotes about writing and motivation.

On leaving school, McGhie joined Shell Oil, which allowed him (unpaid) time off for study at the University of Otago, where he gained an MA (history). His time at university included editing the political page of Critic with Erik Olssen, who later became a professor of history at the institution.

"I used to sell kerosene in South Dunedin, near the Mayfair Theatre. Now, a wet winter’s day in that part of the city was something to be treasured ..." McGhie laughs.

Yet the job at Shell taught the young man a lot about human nature and the priorities of business.

"In the Shell company, if you could not sell, you didn’t get promoted. You could be a great engineer, a great organiser, but until you were shown to be a district manager who could run sales operations, you weren’t seen as someone who could push the company forward.

"I remembered that when I went into foreign affairs: if you can’t get out and talk to people, promote your country or work out ways in which to do so, then you lose the initiative and even your mojo."

Despite being "quite happy" at Shell, McGhie put his name forward for a Ministry of Foreign Affairs interview when a representative visited Dunedin.

The result: in 1965 he headed to Wellington, attached to the United Nations division of the ministry. So began four decades of to and fro around the globe.

In 1967, he was named second-secretary at the New Zealand High Commission in Western Samoa, and played a significant role in helping the nation develop before his return to Wellington in 1970.

It was in the capital that he met a young linguistics lecturer from Victoria University, Caroline Scott. Soon married, the couple headed to New York in 1972, enjoying a period filled with introductions and challenges, as well as social opportunities (including hosting a function for Kiri Te Kanawa at the time of the opera star’s debut at the Metropolitan).

Four years later, the couple (who have no children) returned to Wellington, McGhie heading a training section in Foreign Affairs’ external aid division.

The next step, however, was much more significant: Soviet Russia. Having spent several months in Canada learning conversational Russian, McGhie and his wife arrived in Moscow in late 1979, just before the first of the winter snows. As he recalls: "For anyone posted to Moscow in the midst of the Cold War, expectations, particularly on access to consumer goods, were not high."

McGhie again returned to New Zealand and in the next decade squeezed in two more overseas postings, including as high commissioner to Papua New Guinea, a country struggling to build a democracy at the time. By 1990, he was back in Moscow (as New Zealand ambassador). When he left three years later to return to New Zealand, the Soviet Union was no more.

Amid the various chapters of McGhie’s long career lurk some bizarre moments. During his time as New Zealand ambassador to South Korea (from 1996-1999) he found himself an unintended proponent of Seoul’s subway system having been overheard by Korean media congratulating the city’s mayor on its public transport.

The episode dovetails into another point McGhie would like to make. It has to do with the crunching of numbers, and his distaste for what he describes as "the great managerialist revolution, which holds that if you can’t measure things they don’t exist".

More than a million Seoul residents saw images of McGhie and his wife extolling the virtues of that rail system.

"We were on giant television screens on the streets of the city. Every diplomatic mission in South Korea was deeply envious," he recalls.

"Yet none of this appeared on any management achievement forms, or whatever they called them. I think it was a ‘verifiable performance indicator’."

For a man schooled in the deft dances of diplomacy, it seems he prefers to speak plainly.

As he concludes in Balancing Acts : "The most recent New Zealand Foreign Affairs White Paper was produced so long ago that it now bears a closer relationship to an historical artefact than a document of national value.

"The need for a renewed debate - indeed a national conversation - on foreign policy issues is clear."

Here and there

Gerald McGhie’s career highlights:

• 1965: Wellington, External Aid Division

• 1966: Western Samoa, High Commission, second secretary

• 1970: Wellington, South Pacific Division

• 1972: New York, Consulate General, consul

• 1976: Wellington, External Aid Division

• 1978: Wellington, United Nations Division

• 1979: Ottawa, High Commission, Russian language study; Moscow, Embassy,counsellor and charge d’affaires

• 1982: Wellington, Middle East and African Division

• 1983: Hong Kong, Consulate General, consul general

• 1985: Papua New Guinea, High Commission, high commissioner

• 1988: Wellington, Middle East and African Division, director

• 1990: Moscow, Embassy, ambassador.

• 1993: Wellington, chief of protocol; Wellington, Information and Public AffairsDivision, director

• 1996: Korea, Embassy, ambassador

• 1999: Wellington, Fellow at Victoria University. Joint Fellow of the Institute of PolicyStudies and the Institute of Asian Studies

• 2001: Zimbabwe, High Commission, acting high commissioner; Tonga, High Commission, acting high commissioner

• 2002: New Zealand Institute of International Affairs (director)

• 2002-03: Pacific Cooperation Foundation, foundation trustee

• 2005: Awarded QSO