Dunedin student Zac Mātariki is a hands-on creative from a small township near Whakatāne.

The Otago Polytechnic product design student grew up in a very rural setting in Te Kaha and Omaio.

While attending a private school in rural Northland, he discovered his interest in design.

During his degree, he created his own taonga (pendant) and jewellery box from scratch using traditional concepts with contemporary ideas and materials.

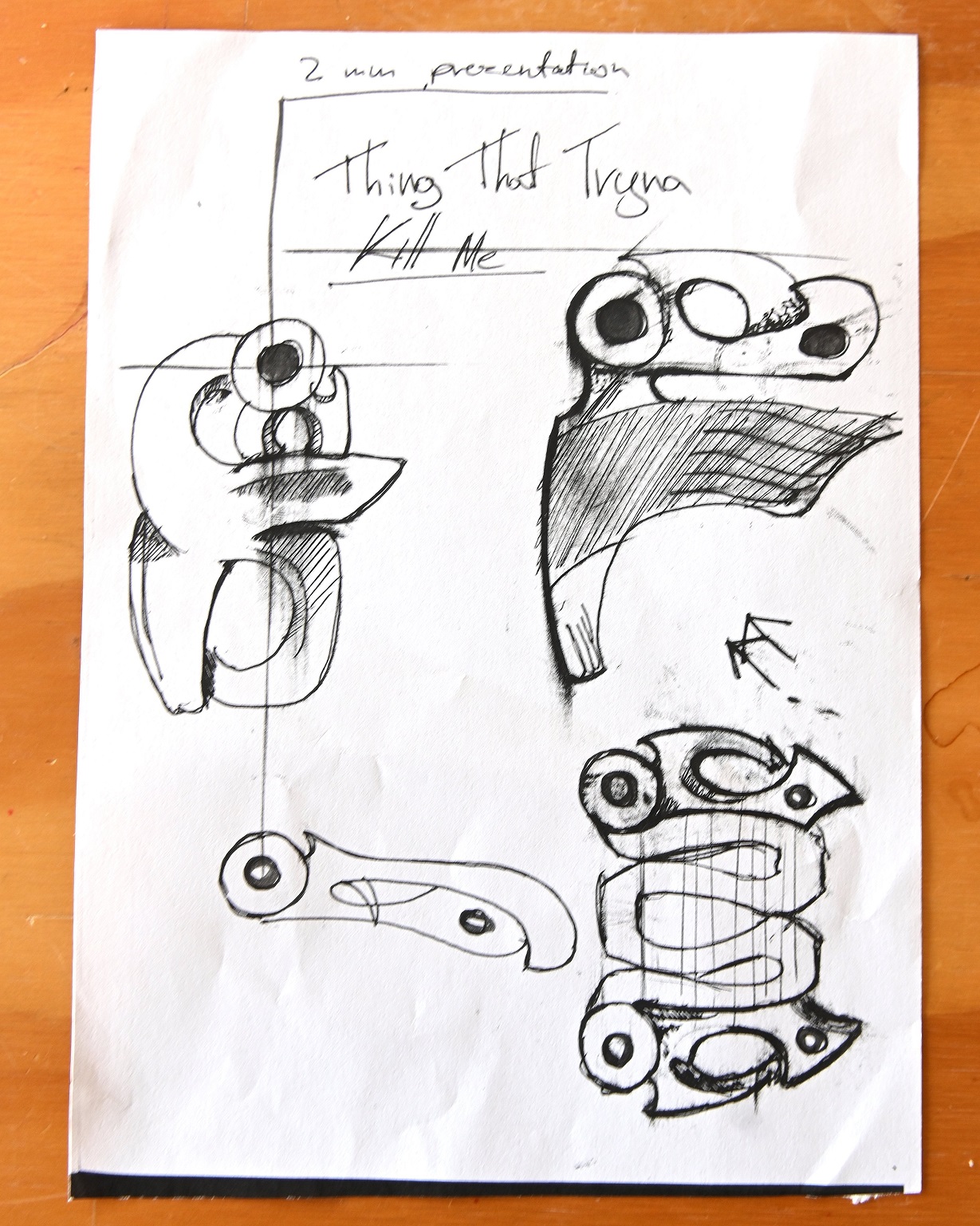

He began by researching Māori contemporary artists who inspired him.

From there, he started sketching and bringing his ideas to life before deciding on his best drawing.

He used the computer software Blender to turn his design into a 3-D shape.

"That takes a while — manipulating it and making sure that it looks right."

Being an experienced carver, Mātariki wanted to make his piece resemble carved wood, a very intricate process.

"The idea is that it’s made out of steel, but it looks like it’s carved."

Once he finished perfecting his digital model, he used a 3-D printer to bring his steel pendant to life.

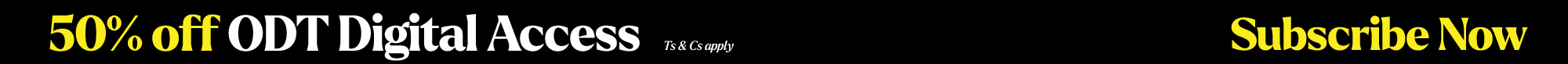

After creating the pendants, he made jewellery boxes out of paua shells to store his taonga.

"I wanted to create something that felt really natural."

"I used a paua shell that I had caught myself — I have a lot of them around."

He carved out a wooden piece to fit closely with the shell before using epoxy resin to create an even more accurate match.

His design and concepts were uniquely his own.

"There’s always been Māori art that’s been appropriated," he said.

"When you create a drawing, or create a new shape or something that’s your own, you’re putting your own soul into it, your wairua into it.

"So that’s the difference — I’m making something that’s new, and I’m using the materials that I have that are accessible to me."

Mātariki was heavily inspired by those who passed on their knowledge to him and the idea Māori artists were free to create whatever they wanted.

"When I go into museums, I get to see all these beautiful taonga, but they’re always behind glass.

"So the only connection I can have with them is a visual one, but there’s so much more to connecting with taonga.

"There’s this whole essence of energy — what it feels like to touch, to hold and to carry with you."

For Mātariki, he appreciated this aspect of his creation the most.

"It’s when it’s done and when I can finally get something in the real world — I can feel it, touch it, gift it, you know, it’s real.

"That’s my favourite part."