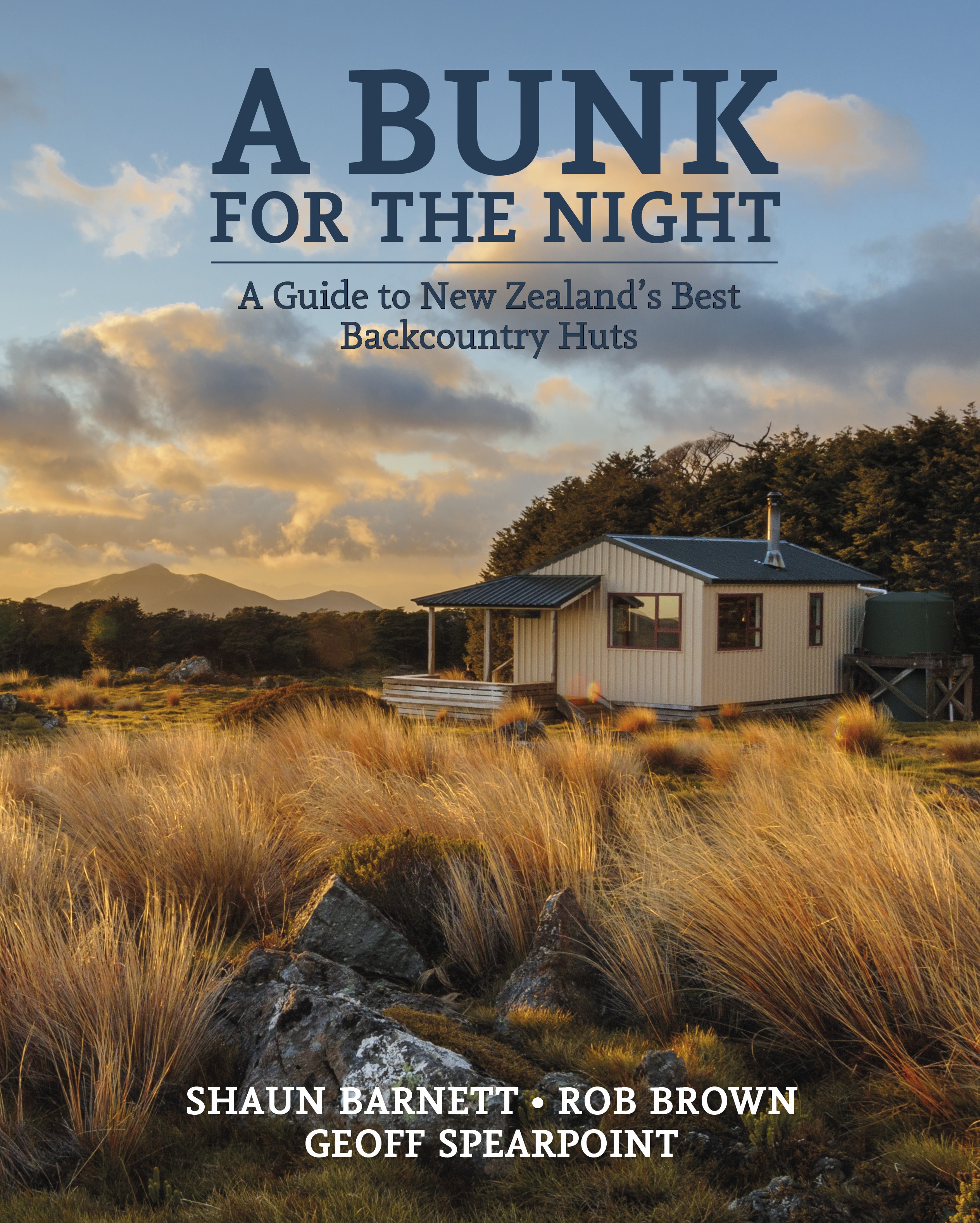

As we start the summer hiking season Shaun Barnett, Rob Brown and Geoff Spearpoint share an extract from their latest book A Bunk for the Night, A Guide to New Zealand’s Best Backcountry Huts.

They have selected a variety of huts, telling their stories and highlighting the need to treat the older huts as ‘‘cultural treasures’’ - looking after them as the country does its biodiversity.

Where: Hawea Conservation Park

Details: 6 bunks, open fire, basic

Stepping through the low door of this old musterers’ hut on to schist flagstones is to step into the past. The open fireplace, the hinges and catch on the door, and the long, low shape of the hut all create a wonderful ambience.

Those who put the hut here chose well. Situated on a dry, sheltered brow at the bushline overlooking the rugged terrain of the Timaru catchment, the hut offered easy access back up on to the tussock tops for farm work. Water springs from a nearby basin, and the bushline provides access to firewood.

Lake Hawea Station was formed in 1910. Stodys Hut was apparently built by the runholders sometime in the 1930s further up the ridge, and then moved to its current site by the Rowleys, who took over the station in 1948. Tom Rowley wrote in the hut logbook on February 20, 2011:

This hut was a Musterers Hut. Part of Lake Hawea Station. When we mustered this block three men would walk up Timaru Creek hunting the sheep up as they came up the valley. Another two men came over the top from the Homestead and came out and mustered the next basin out and then came back to the hut where the Packee would have a meal cooking. We would break camp at four o’clock in the morning and muster through towards the lake. The early start was to catch the sheep before they broke camp and returned to the valley floor. This happened in late October and was the shearing muster for the wether flock.

Over time, as mechanised mustering developed, Stodys became less important for farming. But others began to value it more, and in 2010 Doc spent time and money restoring the old hut for use by trampers, hunters and those walking the Te Araroa Trail. New bunk platforms were installed, flashing around the roof perimeter was added, a flexible brown lining was installed as a condensation barrier, the open fire was made safer with the addition of a steel liner, and a woodshed was built, but all this was done with care to retain something of the original character of the hut. The bare corrugated iron remains unpainted.

Other farming huts in the area have also been renovated, including Junction Hut and Moonlight and Roses Hut, both of which are in the Timaru catchment.

Junction Hut, in the lower Timaru River, belongs to Dingle Burn Station. Significant repairs were carried out in 2013, with the station’s owners, the Meads, supplying the materials and transport, and Derek Parkes and Julie Mador providing the labour. They ask, please enjoy and respect this hut.

Moonlight and Roses Hut, at the bushline about 2km southeast of Dingle Peak, is in particularly good condition. It was built in 1941 for boundary-keeping, mustering and recreational hunting by Timaru River Station, but soon afterwards Dingle Burn Station was carved out of Timaru River Station and the hut went with it. In the mid-1980s, the Forest Service upgraded the hut, adding bunks, mattresses, flooring, new windows, a concrete hearth and a lean-to woodshed. At the conclusion of the stations tenure review in 2003, the hut was incorporated into Hawea Conservation Park, and in 2010 more maintenance was carried out, with the addition of a new bunk and mattresses, new fire-retardant building paper, a new bench and water tank, a new chimney and a steel liner in the fireplace.

The main access to all three huts is along the Timaru River, which can be reached via Timaru Creek Rd from Lake Hawea. Doc signs and a car park just before the Timaru River bridge indicate a mixture of track and riverbed travel upstream, with numerous crossings. Junction Hut will be reached in about 1½ hours, and Moonlight and Roses Hut is a further 3½ hours beyond. Timaru River is popular with trout fishers and hunters, as well as trampers. Upvalley, a Doc sign indicates the steep track to Stodys Hut off the sidle track. Allow 6-7 hours from the Timaru car park to Stodys Hut by this route. A high tops route to Stodys Hut — another section of the Te Araroa Trail — leaves from the shores of Lake Hâwea, and this will take about 8 hours.

- By Geoff Spearpoint

Slaty Creek Hut, West Coast

Where: Waiheke Valley

Details: 4 bunks, open fire, historic, basic

Slaty Creek is a very special place, offering a traditional hut experience. It’s small and rustic, but it keeps you dry and, with the fire going, is very cosy. When the light of flickering flames glows off the rough-hewn walls, it positively oozes authenticity and ambience. If you put all the generic elements of a classic New Zealand bushman’s hut together, it would look, smell and feel like Slaty Creek Hut. This is perhaps not surprising, considering that the deer cullers who built it for the Department of Internal Affairs in 1952 were skilled bushmen in the old style, who used timber from trees in the vicinity. The hut, carefully restored by DOC in 2006, offers its past to the future, unvarnished. A stay here is a refreshing experience, giving an insight into what was standard backcountry hut accommodation until the 1960s.

The hut sits at the fringe of a grass flat in the Waiheke Valley, backed by red beech forest. In gold-rush days a benched pack track led up the valley, over the Main Divide at Amuri Pass and then down the Doubtful Valley to the Lewis River. This pack track is now a well-maintained tramping route. Approaching the hut along this route from the Lewis Road via the Doubtful Valley and Amuri Pass will take about 10 hours. Alternatively, a much shorter route from the west leads up the Ahaura River through Waikiti Downs Station to the Waiheke Valley, taking 3-4 hours. River crossings will be required either way, but it is wonderful tramping country.

On my last trip to Slaty Creek Hut, we arrived via Mid Robinson Hut. Mist and slushy snow on the tops, then windthrow on the bush spur down, left us exhausted. We stumbled upvalley, pushed open the hut door, lit the fire and put on a brew. Wonderful.

- By Graham Spearpoint

Cobb Tent Camp, Tasman

Where: Kahurangi National Park

Details: 3 bunks, open fire, basic

Nelson’s northwestern mountains have long cast a spell over hunters and trampers, and the area is full of interesting huts, many of them historic. Perhaps the most charming, however, lie in the Cobb Valley, which boasts no fewer than four huts -Trilobite, Chaffey, Cobb and Fenella - as well as this wonderfully restored tent camp, now one of only two in the country (the other is the Soper Shelter, constructed in 2016). It’s about 2.5 hours’ easy stroll up the valley.

Set near the burbling Cobb River, among a copse of beech trees and overlooking a red tussock flat, the tent camp occupies an enchanting spot (if a little sunless and shady during winter). It’s a genuine replica of an original deer cullers’ tent camp, fully restored in 2014 by Doc. As anyone who has stayed there can attest, it’s a novel experience to sleep under something that has all of the spaciousness of a hut, but instead of iron has a canvas roof that sighs when the breeze stirs. Through the canvas you might hear bellbirds chime, the river chuckling or beech trees creaking.

Between the 1930s and 1970s, tent camps were commonplace in those parts of the backcountry where deer cullers operated. They were cheaper to build than huts, and could easily be dismantled when needed at a new site. Even after the Forest Service began its extensive hut-building programme in the mid-1950s, cullers continued to use tent camps. One of a trainee’s first tasks at Dip Flat (the Marlborough base where aspirant cullers began their career) was learning how to erect and dismantle a tent camp. Many cullers developed quite an affection for these hybrid huts.

Doc restored the Cobb Tent Camp faithfully to the exact dimensions of an original Forest Service one. It boasts a large corrugated-iron chimney, framed with mountain cedar, a door made from red beech and canvas stretched over a manuka frame. Once through the door, you enter the main room, which has a rough-hewn bench and wooden stools. At the back is a smaller sleeping room, closed off by canvas flaps.

So why does a tent camp still exist in the Cobb Valley? In 1973, Forest Service ranger Max Polglaze oversaw an upgrade of the Cobb Valley Track. His men needed accommodation, so Polglaze erected a tent camp. No doubt it reminded him of his own days as a deer culler the previous decade. During the mid-1980s, ranger Hugh Mytton relocated the camp to its present site. Later still, Doc staff used it on occasions, but the shelter gradually began to disintegrate. Mountain weather is hard on canvas.

By the 21st century, very few tent camps remained. Although almost derelict, the Cobb site was probably the best still surviving. Takaka-based Doc ranger John Taylor badly wanted to save it. He’d already worked on the restoration of several huts in Kahurangi National Park, including Riordans, Waingaro Forks and Chaffey. If he could fix up the old tent camp, it would conclude the last major hut restoration project needed in the Golden Bay area.

Taylor’s shoestring budget wouldn’t stretch far, but the local community responded with keen interest and heartening generosity. Members of the Golden Bay Deerstalkers Association and Friends of the Cobb helped prepare the site by carrying river stones to make a higher, drier foundation. Local suppliers and manufacturers donated canvas and completed all the upholstering for free. In July 2014, with the site prepared and materials transported in by helicopter, Taylor and fellow ranger Tony Hitchcock spent two weeks putting the camp together, working in days that began with heavy frosts. They used skills once common among bushmen but now rarely used, like hand-dressing and cutting the timber with a broad axe.

In November 2014, some 50 people gathered for the official opening of the tent camp. Bellbirds sang, billies of tea swung over the open fire and people devoured camp oven scones with lashings of butter and jam. Max Polglaze was there to see a new era of the old camp he’d put in four decades before.

Now anyone can spend a night in the camp, perhaps experiencing something of the life of the deer cullers of times past.

- By Shaun Barnett