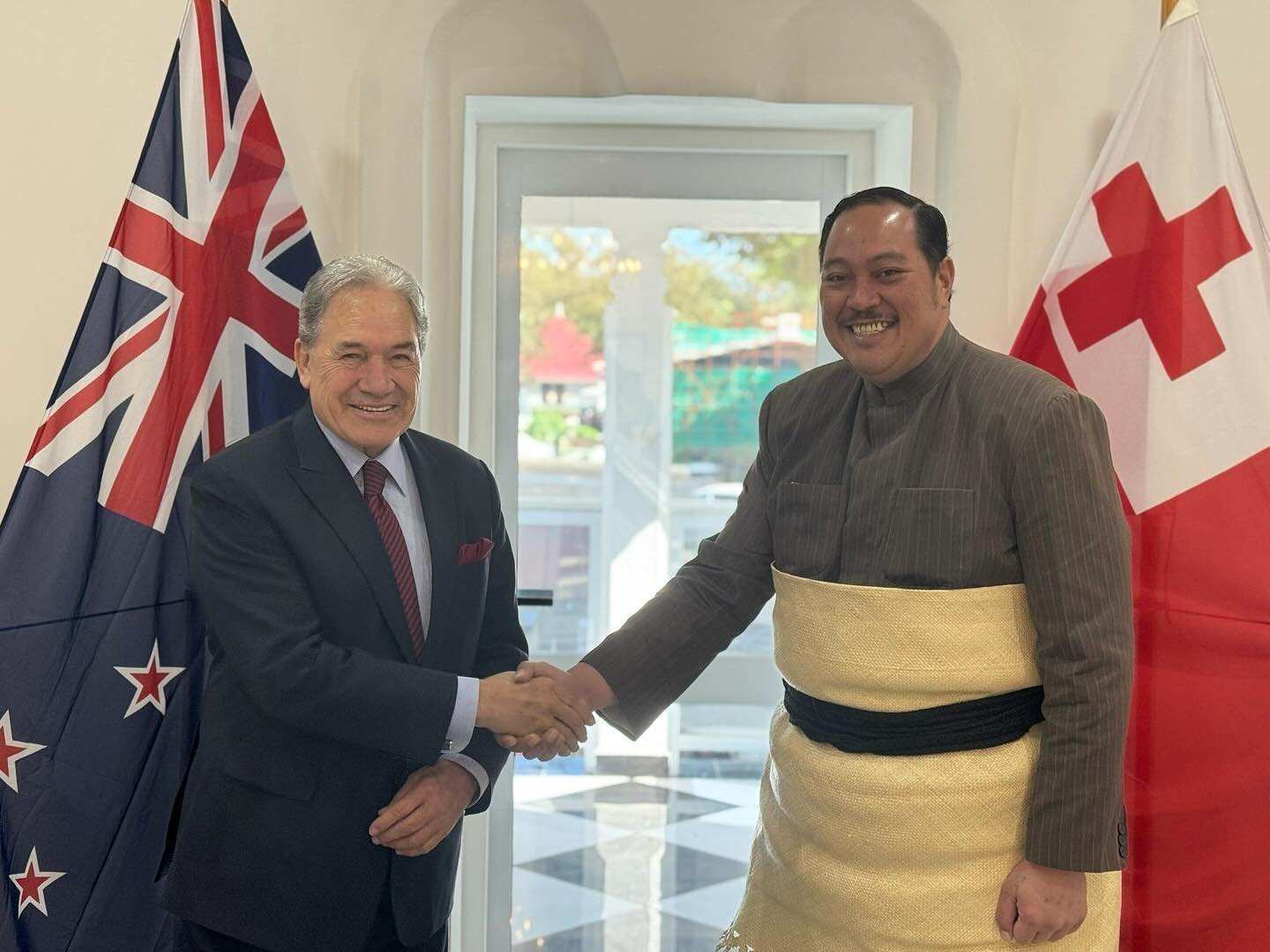

When Winston Peters speaks about political engagement with the South Pacific, he walks his talk.

Midway through his third stint as Minister of Foreign Affairs, Mr Peters has once again demonstrated a commitment to the area which was a hallmark of his previous times in office.

Now, as then, Mr Peters is a conscientious attender of regional conferences and forums; he has also visited 16 of the 17 other Pacific Island Forum member countries personally.

Some of those countries have been visited twice or more, and Mr Peters has also twice taken cross-Parliamentary teams (with MPs from Labour and the Greens as well as National, Act New Zealand and his own New Zealand First party) to the Pacific.

"That’s important to send the message that even with future changes of government, our relationship with the Pacific will remain constant," Mr Peters said.

He will be in Dunedin this week for a duty he has performed several times before, giving the opening speech to the University of Otago’s annual Foreign Policy School.

Now in its 59th year, the school is an annual gathering of politicians, diplomats, academics, students and those interested in diplomacy, to hear a range of papers on the theme of the conference — in 2025 that is "Small Powers and Strategic Competition in the Indo-Pacific" — and also to network.

The foreign minister of the day usually gives the opening speech — although Mr Peters did not do so last year as the conference had a specific focus on health. He is back this year, and speaking on a topic close to his heart.

"Why the Pacific," he asks.

"Well, because it's our neighbourhood. No-one thinks that charity should not begin at home.

While Mr Peters’ reference was to geographic isolation, he also has plenty to say about diplomatic isolation.

As Foreign Minister in Jacinda Ardern’s first term in government, Mr Peters racked up plenty of frequent flyer points going to the Pacific.

He then watched frustrated, out of Parliament and out of power, as his successor Nanaia Mahuta — to his mind — abandoned the region.

While Ms Mahuta did have the reasonable excuse of the Covid pandemic cancelling many of her travel plans, Mr Peters is adamant that a vacuum was left in the Pacific which other powers sought to fill. His hectic travel schedule is an attempt to repair frayed relationships he said.

"Was there a void? It was a huge void. They hadn't seen anybody," Mr Peters said.

"Sadly, many of them hadn't seen anybody in New Zealand either. When diplomats take you aside, shortly after I came back in 2023, and said, we're not there, we were wandering. I said why, they said why do we bother because no-one will talk to us, no one's seen us.

"I then began to realise from a leadership point of view, just how vacuous many of their claims of the leadership were. It was actually a disgrace.

"And so yes, it's been hard work and it's been exhausting for us time-wise, but we've managed to fill it and we've managed to talk to others alongside us as they realised that more had to be done on the Pacific."

And in South East Asia. New Zealand has just signed an enhanced partnership agreement with Vietnam and last week in a speech in Wellington Mr Peters said New Zealand was "working hard" to similarly upgrades in its relationship with the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (Asean) and Singapore.

Coincidentally, the Foreign Policy School is also hosting a roundtable commemorating 50 years of diplomatic relations between New Zealand and Asean.

News of New Zealand’s response — pausing nearly $20 million of core sector support funding for the Cook Islands — emerged last week.

One of the themes of the Foreign Policy School is great power competition between China and United States in the region; the gathering takes place at a time when Chinese interest in the Pacific is as high as ever, and as the US is cutting its aid programmes worldwide, including to the region.

Just as the former presented challenges to New Zealand, the latter presented opportunities Mr Peters said.

"We should always be, though, doing a review of our offshore aid and our offshore expenditure. America is having a massive one at this point in time. And then the second thing you've got to remember is it is their money, taxpayers' money. I think that there's some reasons to be confident that we'll have a greater engagement."

To that end, New Zealand’s Pacific international development co-operation programme has been revamped to focus on fewer, bigger, projects — an emphasis which it hoped means that they will be done better. Projects include efforts to build climate and economic resilience, strengthen governance and security, and to lift heath, education and digital connectivity.

Although not one of Mr Peters’ portfolios, he has been an advocate for greater defence spending, and has urged that with the Pacific very much in mind.

Quite apart from any actual or perceived security threats, Mr Peters well knows that NZDF forces deploy to the region for many reasons, and that the greater role New Zealand can play in surveillance and emergency recovery the more the country is appreciated by its neighbours.

"When you are seeking to talk to people, remember that they don't just talk to you, they look over your shoulder to see what's behind you, or they look at your record. If they find that you're all words and no action, then your level of influence is massively reduced. So that's the first thing," he said.

"Then the second, right across the board ... we are actually expressing the need for greater defence spending. It's important. And remember this, though it's a commitment, the timing of the purchase, the optimisation of that purchase, and the interoperability of those purchases are critical.

"So it's not all here right now, it's going to happen, but at least we've made the commitment, and therefore other countries who are forced to make a commitment will take us more seriously."

• The University of Otago Foreign Policy School, June 27-29.