Now, world-first research led by the University of Otago has discovered how it happens.

Otago neuroendocrinologist Associate Prof Karl Iremonger has found stress-controlling brain cells, called stress neurons, switch on and off in a steady rhythm, about once every hour.

But if they are over-activated, it can result in mental health and stress-related health conditions.

"Even when we’re in a calm, resting state, what we’ve discovered is that these stress neurons are still turning on and off, and this activity is actually important for the normal patterns of stress hormone release in our body that exist in a normal 24-hour day.

"So if you look at the level of stress hormone in your body, it’s actually quite surprising to find the levels are actually very high first thing in the morning when we get out of bed.

"And to many people, that’s really surprising because they say, ‘I’m not stressed out. I’m actually probably highly relaxed after a night’s sleep’.

"But this is our body’s natural rhythm and, in fact, these hormone levels being high when we wake up is our body’s way of getting us ready for the potential challenges and stresses of the day ahead."

He said the research showed the neurons were also important in controlling stress hormones such as cortisol.

"When they turn on, they also help increase wakefulness — they are driving an increased, physical activity state.

"So the two systems co-ordinated together are a part of our brain’s waking system."

However, if the neurons became over-activated by external threats or chronic stress, it could result in changes in mood and disrupted sleep.

"Too much stress hormone release, too much activation of these stress circuits, can lead to mental health conditions and other health disorders.

"So what we’re really interested in is trying to develop ways to modulate the system to be able to shut down the activity of these brain cells in conditions where they become too activated.

"And that will help us with a lot of mental health conditions and stress-related health conditions."

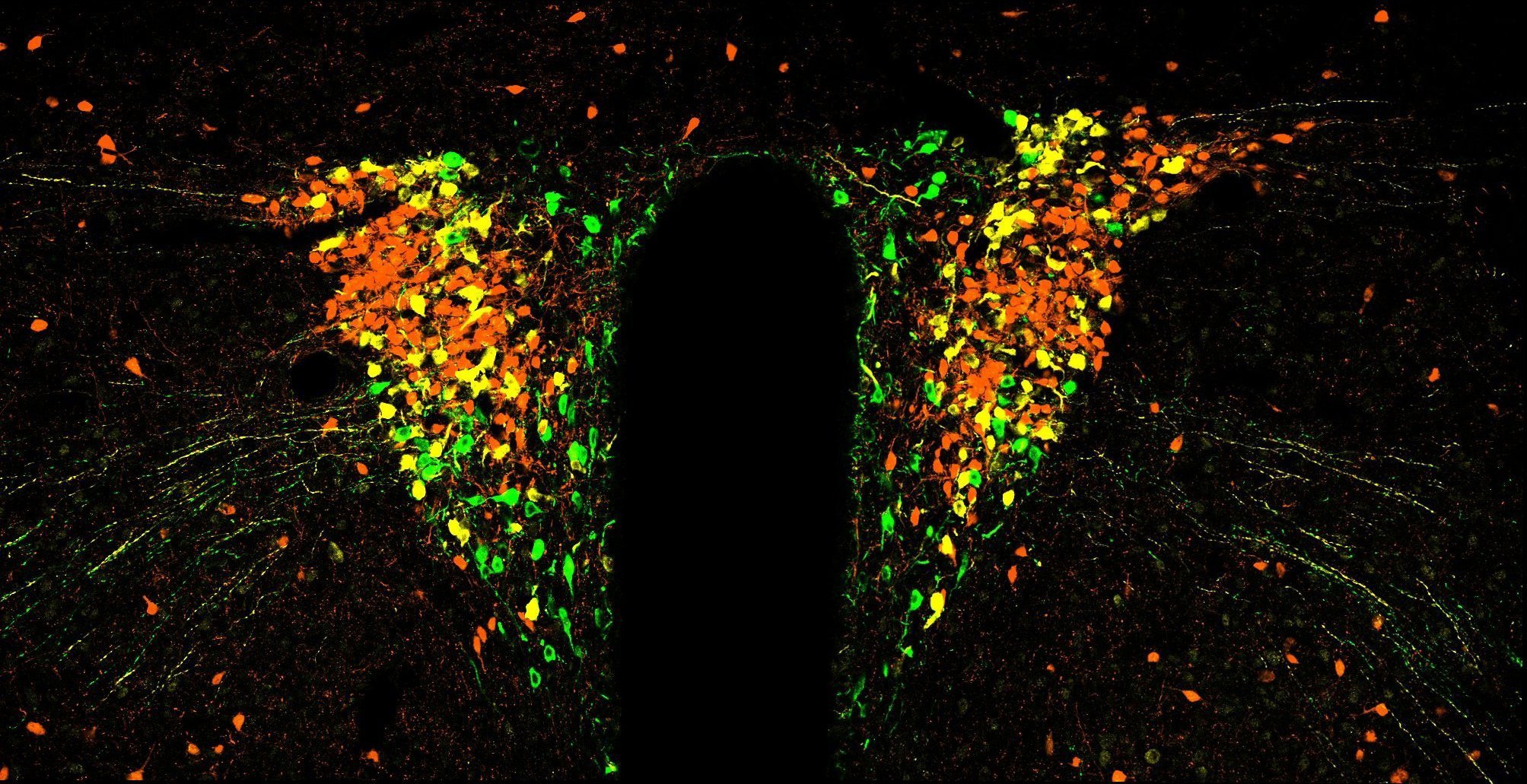

The researchers used an optical technique called photometry to track brain cell activity of mice and rats over the day and night as they moved around freely.

"A group of brain cells called corticotropin-releasing hormone [CRH] neurons were found to be particularly important for the daily rhythms of stress hormone release.

"We also found when the CRH neurons were artificially activated, this changed the animals’ behaviour. Animals that were previously quietly resting became hyper-active."

Prof Iremonger said the research findings might lead to a better understanding of how disrupted stress rhythms could result in changes in mood and disrupted sleep.

Drugs that decreased CRH stress neuron activity might also be beneficial in treating conditions associated with hyper-active stress responses, he said.

"Knowing how these brain signals work will help us understand the links between stress hormone levels, alertness and mental health."