Grant Robertson has failed to do so for several years but he can be forgiven for that. A pandemic will tend to alter the best-laid projections of Treasury analysts.

One of the most striking things about the 2022 Budget was Mr Robertson’s confident prediction that New Zealand would be back in surplus by 2024-25.

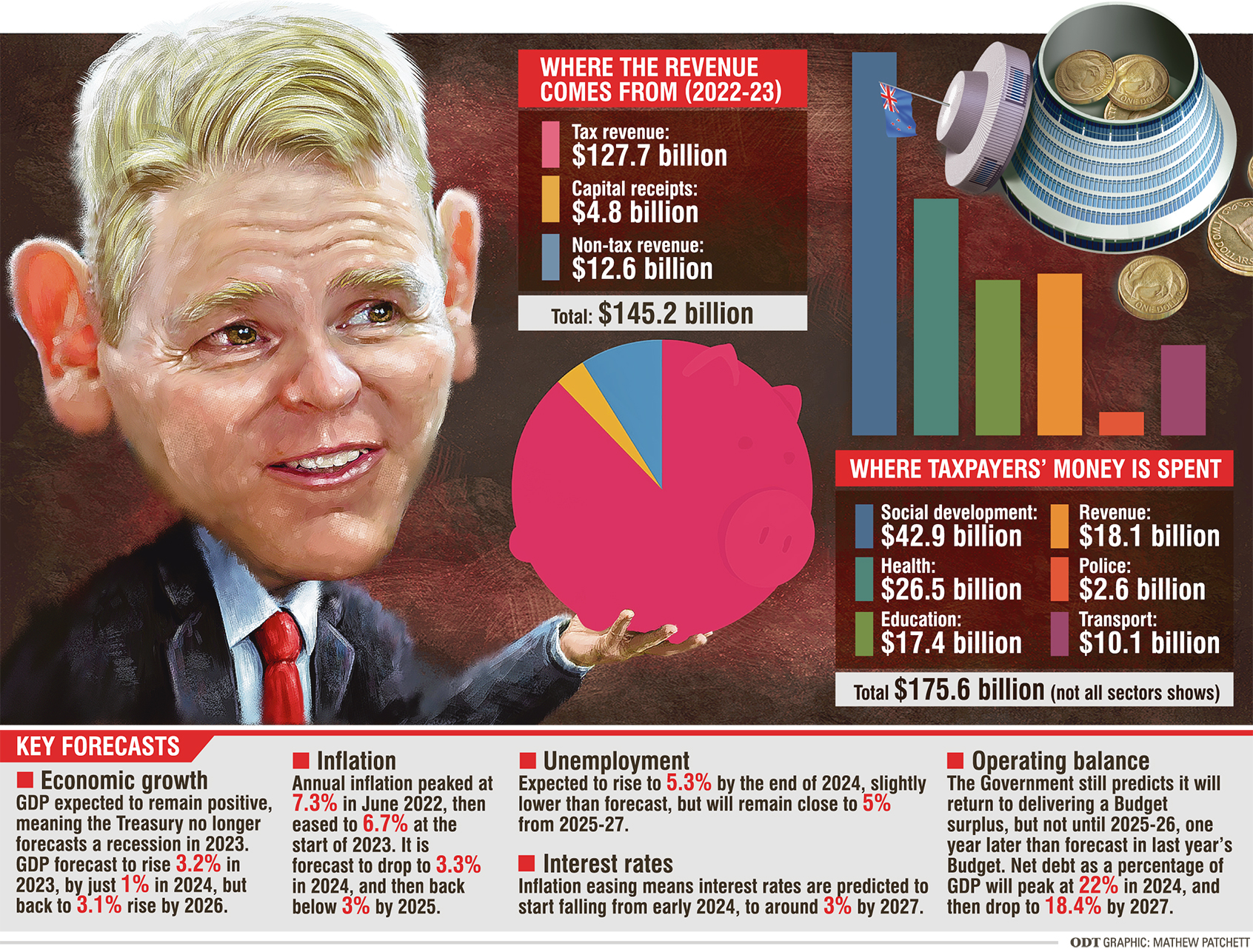

Yesterday, in Budget 2023, Mr Robertson quietly tip-toed back a little from that bullish statement. A surplus is likely but not until 2025-26.

Again, the Finance Minister has been beset by misfortune. Cyclone Gabrielle and the associated cost of the rebuild has slowed progress, and Covid-19 is still very much a drag on the economy.

The holy grail has moved beyond Mr Robertson’s grasp for now, but his forecasts suggest it does look tantalisingly close.

It has been long expected the New Zealand economy would dive into recession this year, but the Treasury is now suggesting otherwise.

GDP growth will likely drop to an anaemic 1% next year, which makes recession avoidance a knife-edge proposition, but is anticipated to climb back to about 3% by 2026 and 2027.

By coincidence, 2026 is also when the holy grail is expected to be seized.

But the thing about the holy grail is that it proved elusive to most who quested after it, and there are still some worrying numbers in this Budget.

The supposition upon which the forecasting rests is that the annual inflation rate, which is slowly starting to drop, will rush back as fast as it soared. It is meant to almost halve, from 6.3 to 3.3 by 2024, which seems as heroic assumption, and then nestle back close to the band in which the Reserve Bank is meant to keep it.

Relatedly, interest rates are also expected to drop from early 2024, to around 3% by 2027.

Given where the Official Cash Rate and bank interest rates sit, it — again — seems a glass half full surmise that both inflation and interest rates will drop that quickly, even if homeowners about to have to refix their mortgages might wish they would.

They also face the fact that the value of their homes has fallen by nearly 17% from their peak and are predicted to keep falling. Balancing the desirability of housing affordability with the spectre of negative equity is another trouble Mr Robertson still has to solve.

When costs go up, spending cuts are made — and Mr Robertson ‘‘reprioritised’’ several billion dollars of expenditure in recent weeks.

Despite that, both operational and capital expenditure are higher than predicted in the Budget Policy Statement.

Mr Robertson has blamed inflation and weather events and said Crown expenditure as a share of GDP is forecast to drop, while Crown revenues hold steady.

It will be a delicate balance though, and it is a complex and easily dislodged set of assumptions which all add up to his hoped for surplus.

Mr Robertson will have wanted to proclaim the surplus would arrive next year but grim recognition of the economic headwinds still buffeting New Zealand meant that he could not be that triumphant.

Getting to claim a surplus next year, should Mr Robertson still be the Finance Minister, may still be a stretch on these numbers, but at least the holy grail is still twinkling in the near distance.