The last time I attempted to write verse I produced a muddled mess of similes, metaphors and unwieldy rhymes. As I recall, the poem was about life in the ocean and featured innumerable descriptions of gleaming coral, toothy sharks and bumbling beluga whales. Wordsworth, I was not.

But at least I know I can’t write poetry. A certain William McGonagall did not.

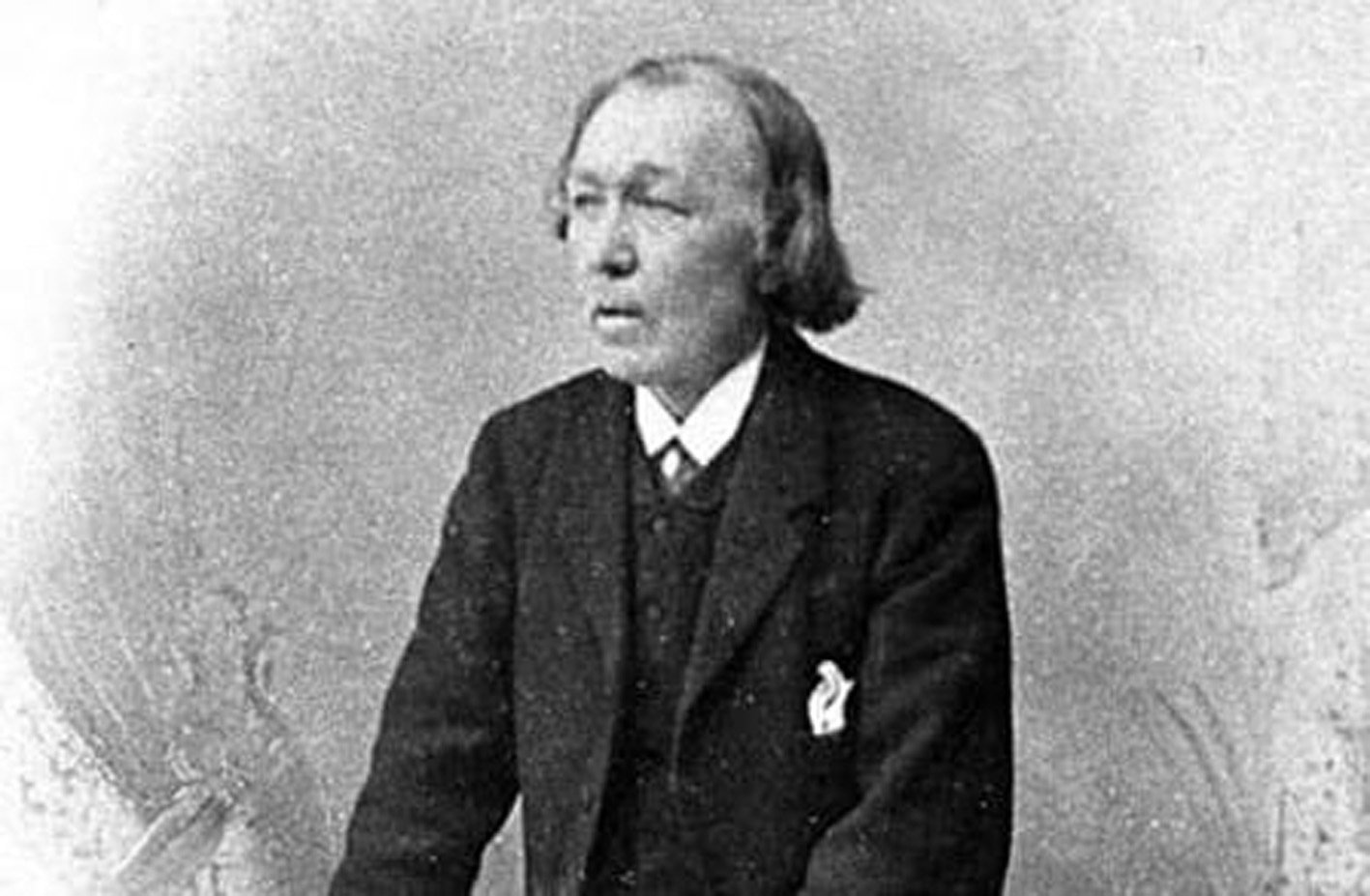

Largely self-educated, McGonagall initially decided to pursue a career on the stage, where his outlandish exploits, most memorably his refusal to die while playing Macbeth (he believed the actor playing Macduff was envious of him) hinted at the gargantuan self-confidence that would define his later life.

Following a poetic epiphany in his 50s, McGonagall decided to make a living from his verses, hawking broadsides and performing to often riotous audiences who pelted him with rotten eggs, flour, stale bread, potatoes and fish. Gloriously undeterred, McGonagall ploughed on, even appealing to Queen Victoria (unsuccessfully) for patronage.

McGonagall persisted with writing horrendously bad poetry until his death in poverty in 1902, leaving behind a body of verse still enjoyed for its accidental comic genius and a memorial bench in Greyfriars Kirkyard bearing the inscription "Feeling tired and need a seat? Sit down here, and rest your feet."

But what is it that makes his poetry so bad? Let me count the ways.

McGonagall’s romantic verse is strictly narrative in style, completely lacking any simile or metaphor. Frequently inspired by natural disasters or bloody war, the poems lack any sense of imagination or imagery and are choppy and inconsistent in terms of rhythm and meter. Then there’s the flat diction, weak vocabulary and forced rhymes — his poems often read like accident reports disguised as nursery rhymes.

McGonagall’s poems are so unrelentingly banal that they become humorous — they’re so bad they’re good!

Don’t take my word for it — let us examine McGonagall’s most infamous poem, The Tay Bridge Disaster, written in 1880 following the collapse of the eponymous structure during a severe gale.

"Beautiful Railway Bridge of the Silv’ry Tay!" he begins enthusiastically, "Alas! I am very sorry to say / That ninety lives have been taken away / On the last Sabbath day of 1879, / Which will be remember’d for a very long time."

The poem continues in this vein, cheerfully moralising the tragedy that robbed 75 people of their lives (not 90, as McGonagall states). He blithely summarises the shock of the people of Dundee with such immortal lines: "And the cry rang out all round the town, / Good heavens! The Tay Bridge has blown down."

McGonagall’s recitations became just as infamous as the verses themselves and he became something of a comic music hall character, performing most frequently at pubs despite his hatred of alcohol. Notwithstanding his denouncement of publicans for causing sin, McGonagall saw nothing wrong with performing at such establishments "to an accompaniment of whistles and cat-calls" and "a shower of apples and oranges", to quote a contemporary reviewer. On one occasion he was pelted with peas after reciting a verse about the evils of "strong drink".

Beyond the unintentional hilarity of the verse, McGonagall’s poetry brings me joy in several ways.

Firstly, his poems are pedagogically valuable in that they teach rhyme, metre, tone and bathos precisely because they get them wrong so consistently.

By studying McGonagall’s verse, you can learn a lot about what not to do.

And then there’s his sincerity — McGonagall genuinely believed he was a great poet. There’s no winking irony or self-awareness to his verse; there’s no cushion for his mistakes. The absolute earnestness of his poetry render McGonagall’s failures ever more acute and yet more funny.

We modern audiences have become so inured to irony and parody that there is something delightfully disarming about a man who tried so hard and missed the mark so completely.

Moreover, there’s the fact that despite all the abuse and miscellaneous foodstuffs hurled at his person, McGonagall’s poems are rarely cruel. Rather, his verses are moral, civic-minded and well-intentioned, with a certain naive decency that feels oddly refreshing.

Consider for instance his poem on women’s suffrage: "Fellow men! why should the lords try to despise / And prohibit women from having the benefit of the parliamentary Franchise? / When they pay the same taxes as you and me, / I consider they ought to have the same liberty."

He’s got my vote, although perhaps he would not approve of my dress-sense; "When women will have a parliamentary vote, / And many of them, I hope, will wear a better petticoat."

Then there’s his tendency to violate literary expectations in visible ways. McGonagall’s rhymes are obvious, forced or painfully predictable and the metre lurches along like a war veteran before collapsing mid-line.

Elevated subjects such as the aforementioned train crash or Queen Victoria are described in flat, prosaic language.

Readers can see the very machinery of the genre failing and, in doing so, his poems become comic objects.

In a sense, however, it’s McGonagall who has had the last laugh. Many better poets have been forgotten — countless peers have fallen by the literary wayside, languishing in ignominy, their verses unread, their rhymes unuttered, their efforts unappreciated. McGonagall, however, has survived, even as a subject of ridicule.

There’s an incorrigible durability to McGonagall’s efforts; his poems are memorable; his voice is distinct; and his earnestness is undeniable, pathetic and rather touching. Perhaps McGonagall survives not because he failed, but because he failed so publicly, persistently and wholly without bitterness.

Never did McGonagall exhibit anything in the way of recognition of, or concern for, his peers’ opinions of his work.

I can’t help but admire the man who continued to pen outrageously bad poetry in the face of such censure, not to mention flying vegetables.

May the (lesser) Bard live on.

•Jean Balchin is an ODT columnist who has started a new life in Edinburgh.