"You cannot arrest your way to social cohesion. You cannot regulate your way to fewer grievances. You cannot spy your way to less youth radicalisation."

The answer, it is argued, lies instead in "whole of government, whole of community, whole of society responses".

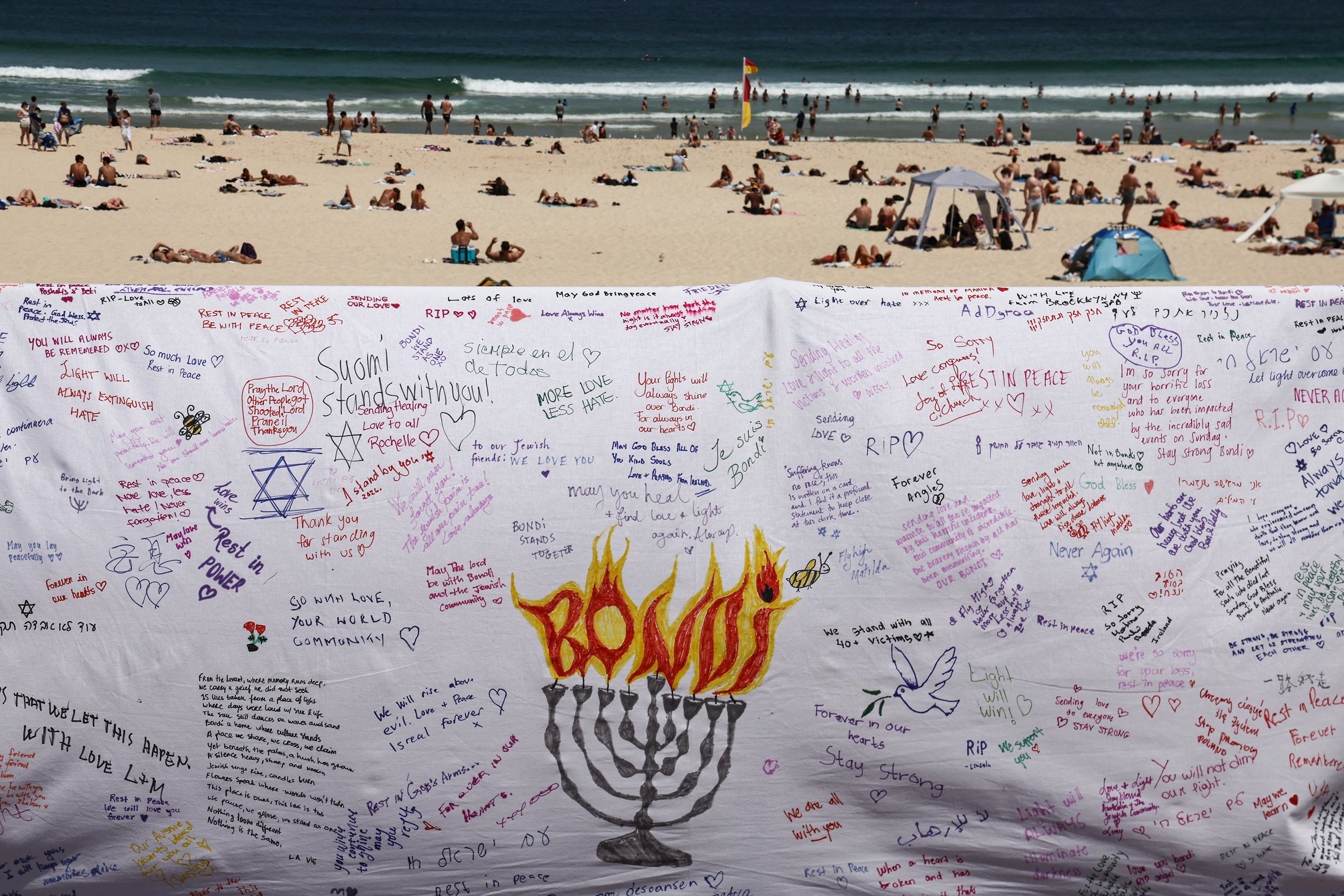

Those words resonate painfully in the aftermath of the recent terrorist attack at Bondi.

Like so many across Australia and New Zealand, I watched with grief and disbelief as ordinary people going about an ordinary day were confronted by sudden, brutal violence. The instinctive response, understandably, is to ask what laws failed, what agencies missed the warning signs, and what new powers might prevent the next atrocity.

Those questions matter. But they are not enough.

If violence of this nature is only met with sharper policing and heavier surveillance, we will treat symptoms while neglecting causes. The deeper question is not simply how do we stop attacks, but what kind of society are we becoming?

When we speak of "community" and "society responses", we are talking about far more than official programmes or government funding lines. Community is not a policy lever; it is a lived reality.

It is formed — or eroded — through families, schools, churches, mosques, synagogues, neighbourhoods, sporting clubs and voluntary associations. It is shaped by whether people feel known, valued and accountable to one another, or anonymous, disposable and unheard.

From a Christian perspective — particularly an evangelical and Reformed one — this moment calls us to recover a moral and spiritual imagination that has been steadily thinned out of public life.

Christianity begins with a clear-eyed realism about the human condition. The Bible does not flatter us. It teaches that violence, alienation and rage are not merely social failures but spiritual ones, flowing from hearts disordered by sin.

We should not be surprised when a society that has pushed God to the margins struggles to articulate why human life is sacred, why restraint matters, or why love of neighbour is more than a slogan.

At the centre of the Christian faith stands Jesus Christ, Lord and Saviour of the world. He does not offer a quick fix or a technocratic solution. He offers reconciliation — between God and humanity, and therefore between human beings themselves.

The gospel insists that peace is not first imposed from above but grows from transformed hearts. "Blessed are the peacemakers," Jesus says, not the peace-enforcers alone.

A "whole of society" response therefore must include a moral renewal, not just institutional reform. It means forming people — especially the young — in virtues that resist radicalisation: patience, self-control, empathy, truthfulness, courage and hope.

These are not generated by algorithms or legislation. They are cultivated over time, through relationships, discipline, worship and shared stories about what life is for.

Churches have a particular responsibility here. If we speak of putting Jesus back at the centre of society, that must begin with putting him back at the centre of our churches and lives — not as a cultural symbol or political mascot, but as the crucified and risen Lord who commands repentance, forgiveness and love of enemy.

Evangelical Christianity at its best does not retreat into private piety nor shout from the sidelines. It embeds itself locally: mentoring young people, supporting families under strain, welcoming the lonely, visiting the troubled and naming evil without surrendering to hatred.

This also challenges the wider community. Social cohesion does not mean the absence of disagreement; it means the presence of shared moral ground robust enough to hold disagreement without violence.

A society that cannot say what it stands for will eventually struggle to say what it stands against.

In New Zealand, watching events at Bondi from across the Tasman, we would be naive to think ourselves immune. Our own social fractures — loneliness, youth disaffection, loss of purpose and quiet despair — are visible enough. The question is whether we will respond by doubling down on control, or by rebuilding the relational and spiritual foundations that make control less necessary.

Government has its role. Police and intelligence services do essential work. But they cannot manufacture meaning, belonging, or hope. Those grow where communities take responsibility for one another, and where society rediscovers that it is answerable to truths larger than itself.

At such moments, Christians are called not merely to comment, but to witness — to live in ways that demonstrate a different centre of gravity. In placing Jesus Christ back at the heart of our communities and our common life, we are not imposing a theocracy.

We are recovering a vision of humanity grounded in dignity, accountability, mercy and peace. That is not a soft response to violence. It is the hardest and most enduring one of all.

■ Tony Martin is a Dunedin minister and former military chaplain.