To mark the centennial the country’s only public broadcaster, Radio New Zealand, will fund Centenary Scholarships to be awarded to five of the best journalism students in the country.

Not surprising, really, as Radio New Zealand has little to celebrate. Audience figures are down and budgets are cut. For all the talk about good figures for websites, podcasts and what not, the sad fact is that listening to live radio is declining.

It doesn’t mean that the broadcasters are doing a bad job. It just means that technology has changed the landscape and turning on your radio to catch the cricket score is — like sending a telegram — something quaint that granddad used to do.

If anyone delves into the history of public radio during the next week, they may well suggest that it started on November 20, 1925, when the Radio Broadcasting Company (RBC) — Radio New Zealand’s ancestor — began broadcasting from 1YA Auckland, a private station purchased by the company.

They would be wrong. The Radio Broadcasting Company, having bought Fred O’Neill’s Dunedin station 4YA, made its first broadcast from the Dunedin and South Seas Exhibition at Logan Park three days earlier, on November 17, using the callsign VLDN.

The Radio Committee of the Exhibition hoped that not only musical programmes would be broadcast but that the general excitement of Exhibition would be heard far and wide.

"The great tug-or-war will be so realistically reproduced and accompanied by such complete description by the announcer that the listener will find himself entering fully into the spirit of the event. The shrieks of delight from the scenic railway and the thousand and one sounds and noises one expects at the Exhibition will all be passed on to the listeners throughout Australasia."

It all began with the speeches of the opening along with music from the Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders Band and items by the Exhibition Choir and soloists. The broadcast was not a technical triumph and the RBC was quick to defend its efforts, revealing problems that Radio New Zealand never has to face.

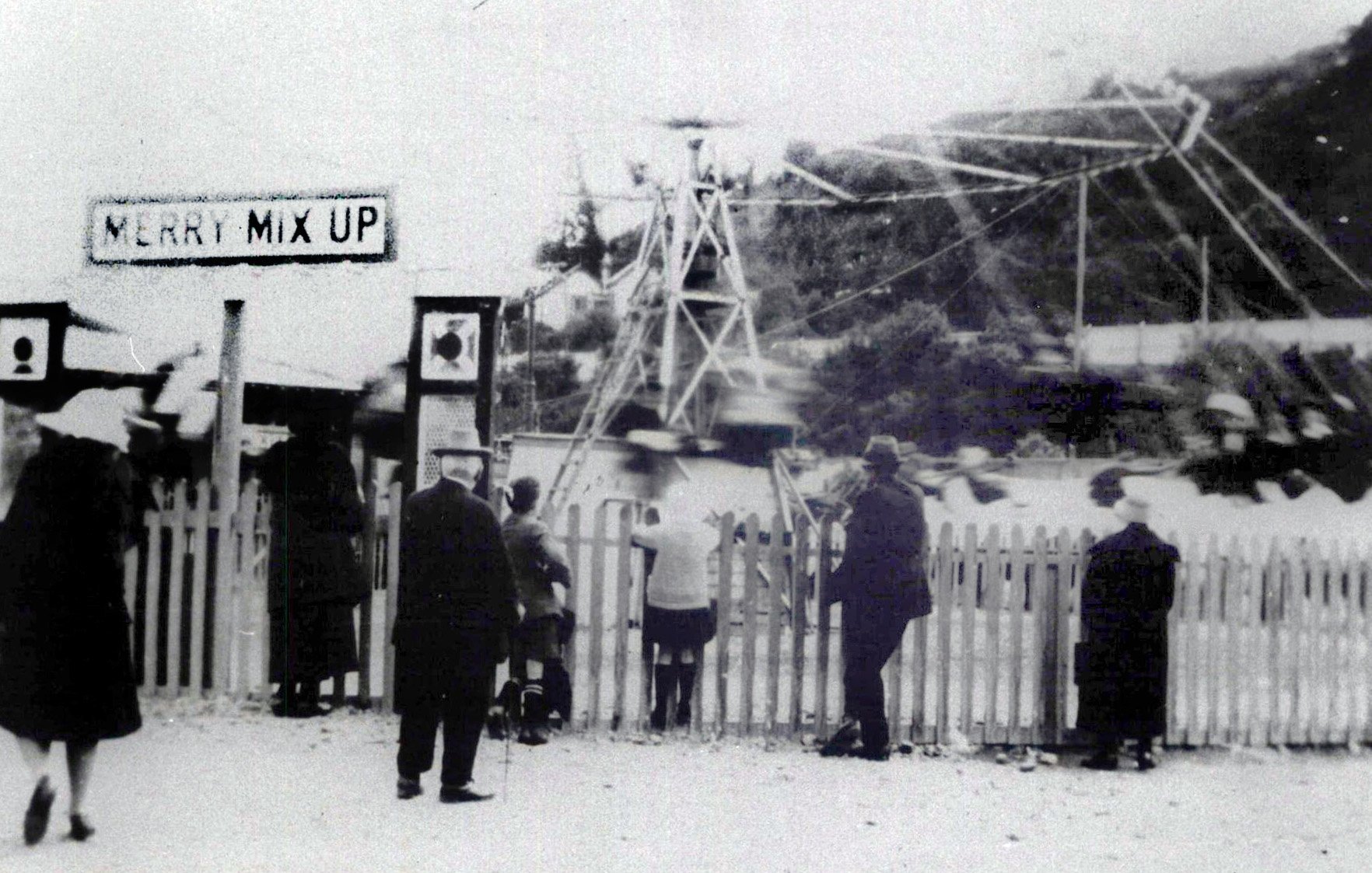

The transmitter, with high hills on three sides, was in "the worst location that could have been obtained". As well, underneath the aerials was the "Dodgem Car" and the "Merry Mix-Up" both driven by electric power.

The sparks from the dodgems affected the power lines and "the whole has a disturbing effect on the transmissions".

It was pointed out that the various artists were performing for their live audience and not primarily for broadcasting and so little regard was given to the relative position of the artist and the microphone. In fact, VLDN had not been allotted enough space to provide a proper radio studio.

The 300sq ft of the "broadcasting parlour" had to accommodate a piano and gramophone leaving no room for artists and instruments. "One hundred sq ft would make a moderate-sized bathroom, but not a broadcast station," complained the RBC.

Despite all this, the first broadcast was eagerly awaited as listeners huddled around radio sets to hear words and music from afar. In Oamaru a group gathered in a small room and "heard the whole of the speeches, band-playing and cheering as clearly and distinctly as if they had been seated a few yards from the official platform. It is almost baffling to the imagination. The valve wireless set is the wonder of the age. In a few years' time people in the country districts will be able to enjoy concerts, lectures, and musical programmes with the same facility as if they were resident in the cities. Broadcasting has conquered distance. It has brought the back blocks into close communication with the centres. It has solved problems of social intercourse. What the next half century will produce, in the way of electrical discovery, one dare not speculate. The world of science is advancing so rapidly that the revelations in the years to come will be astounding."

The next half-century brought commercial radio with ads for soap powder and television with mind-numbing soap operas. The full century brought a media world in which hearing a military band and shrieks of delight from a scenic railway would be old hat. A world where the excitement of live, free-to-air broadcasting is a poor relation.

But the great leap forward began in Dunedin 100 years ago and Radio New Zealand is still on the air. Good on them.

— Jim Sullivan is a Patearoa writer.