Unborn, perhaps? Trying to stay awake to catch Santa in the act? Playing Santa yourself, to children who are now middle-aged with grown-up children of their own?

I was at Moose Jaw railway station, Saskatchewan, and I have a strip of three and a-half photos to prove it.

If you spit a good one at -40°C it’s frozen by the time you put your boot on it. Hitch by the road for half an hour in -40°C and you get frostbite on the skin beneath your eyes.

So, on the evening of Christmas Eve in frozen Moose Jaw, I bought a ticket for the train going east.

In the barn-sized waiting room, I was the only passenger.

When the train failed to arrive the station master came out from his little office to tell me it was frozen solid in Medicine Hat.

"She’s fruz up in the Hat" were his words. He suggested I catch some sleep and he’d wake me when it came.

He woke me at 1.30 on Christmas morning. The train was still fruz up. They were sending a bus for me.

He gave me a cup of coffee. I had half an hour to kill.

There was an automatic photo booth in the waiting room — a little privacy curtain, a single stool which you spun to raise or lower it, a slot for your money, and outside on the wall the rack where your still-wet black-and-white photos emerged, or sometimes failed to, a few minutes later.

In these days of limitless selfies, it is hard to recall the lure and novelty of the photo booth.

They stood at railway stations, bus stations, airports, the foyers of cinemas, anywhere people might gather with time on their hands.

Primarily for passport photos, they cried out to the young to be used for joke pics, pulled faces, tumultuous party snaps, down-trous, snogging, clowning. I’ve got a few of those.

But better were the solitary jobs, the reflexive, capture-the-moment strips of four.

The danger always was self-consciousness. You knew the camera was about to flash. You posed. You lied a little.

But here in Moose Jaw, well, I may have been too tired to lie.

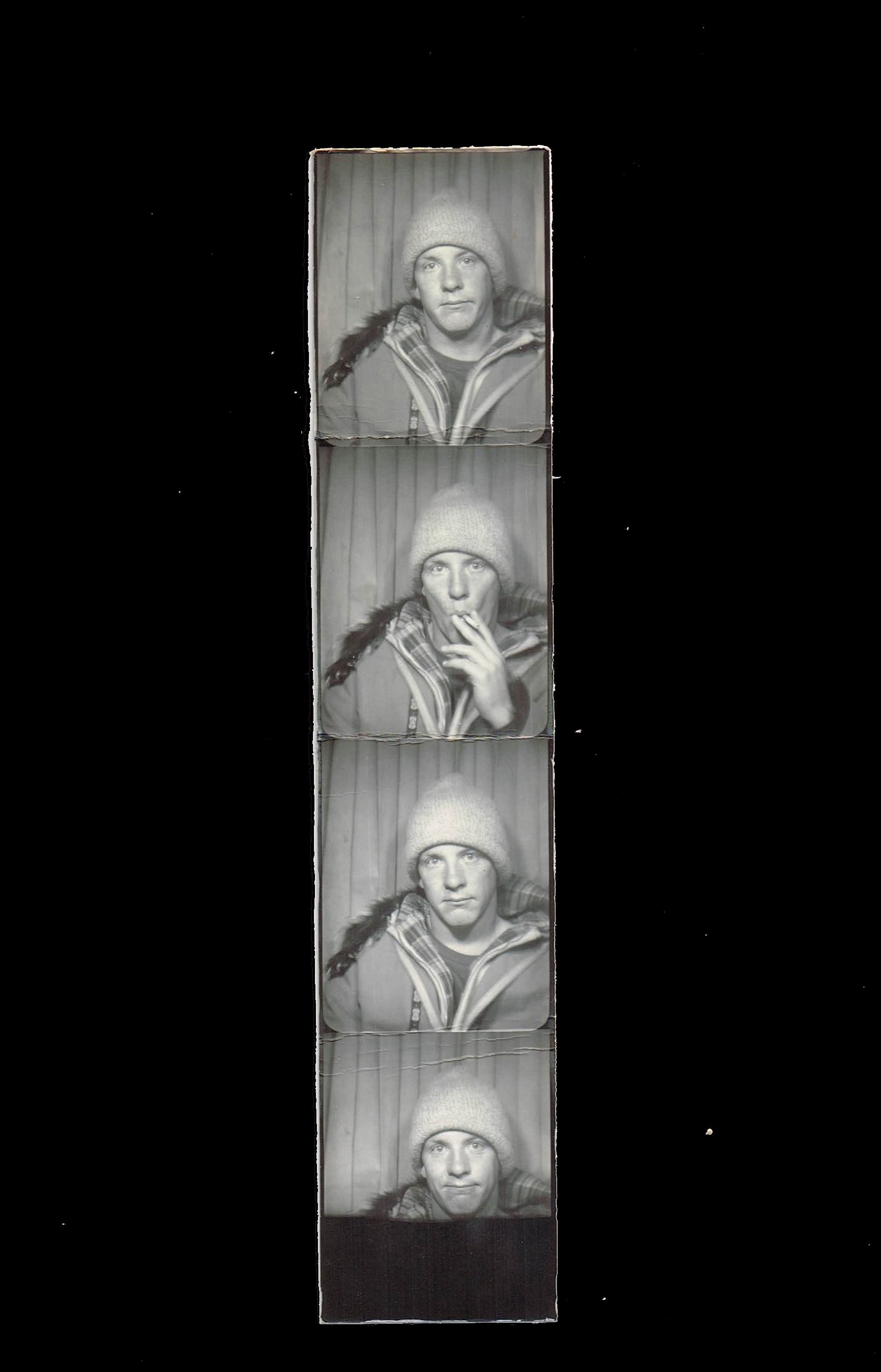

I’m wearing a thick-knit bobble hat, a thermal T-shirt, a plaid shirt and, open at the neck, a heavy jacket, the hood of which was trimmed with wolverine fur.

A woman I knew on the west coast had forced the jacket on me when she heard where I was going, afraid that I was not taking the prairie winter seriously and would die of the cold.

The thing was like a bomb-defuser’s coat, a mighty thermal wall against -40°C.

I was 26. From the neck of the jacket stares a bland and unlined face, pitched slightly to the right.

In the first frame I look resigned to the weariness of travel, perhaps a little peeved, I am not sure.

In the second I am drawing on a cigarette, the cheeks hollowed with the suck of breath, the eyes still fixed on the camera lens, the cigarette held loosely between the first two fingers of the left hand.

For 40 years the left was my smoking hand, those fingers yellowed, fragrant. To see that image now is to taste the bite of tobacco, the calming pleasure of the smoke itself, the contemplative punctuation of the day that it provided. If I had a smoke in the house right now I’d light it.

The third is the philosopher’s shot, a deep stare into the camera’s gut and a sense of the randomness of here and now.

While the fourth frame, half-blackened by some error, is a sort of shrug. I am about to board a bus towards what happens to happen, the next leg of an unknown future.

I thought a lot about the future then. I don’t now. I’ve seen it.

I came across these snaps last night when looking for something else and they’ve haunted me since.

All photographs are lies. The world does not stand still like that.

But is there anything more poignant?

• Joe Bennett is a Lyttelton writer.