The dustpan brush sweeps quickly across the makeshift mainstreet billboard, leaving a generous smear of paste.

Posters follow in quick succession. This is public art improv, performed with daylight stealth.

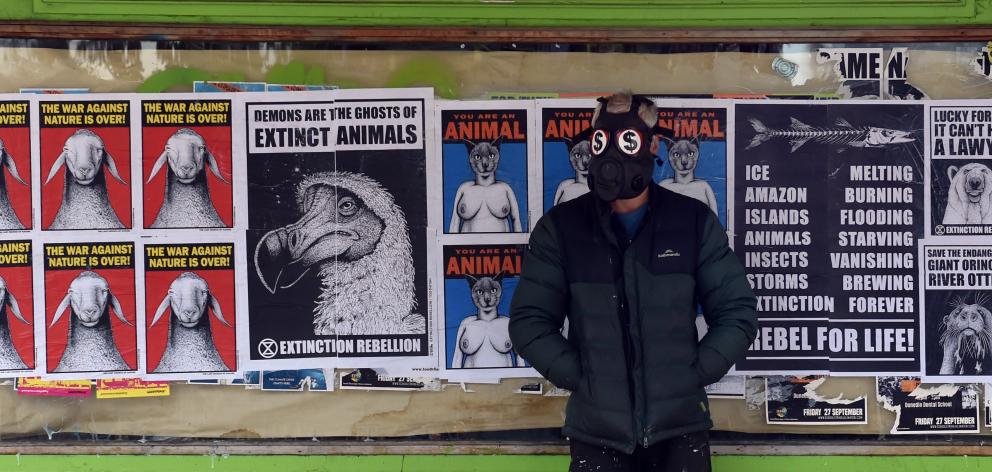

In short order a cast of characters fills the space: sheep, dodo, cat, bear, otter. Or is it a cat? A skull.

It’s early evening and the engine noises caught between the facing low-rises of Dunedin’s George St have a homeward purpose about them. In contrast, the few feet on the street have a light step and passing chatter releases the recently uncorked excitement of the hours after work.

The posters unfurling across the long-empty window of a vacant shop have become fixtures of the Dunedin streetscape in recent times. The city has joined tens of others around the world where agitprop street artist Toothfish has operated; London, Paris, New York, Dunedin.

"This is the first poster," Toothfish says as the uptown sheep go up. One, two, three, four, five, six.

Could this blackened window have once opened into a butcher’s shop? There would be irony there.

"The war against nature is over," the poster declares.

Would that it were so.

"This is the one that came out in 2010," Toothfish recalls. "When the Pope said he didn’t like Avatar because it encouraged nature worship."

"So I thought nature worship is exactly what we need," Toothfish says.

There is small print along the bottom of the poster: provocatively "The Last Church of Nature".

"It is obviously a bit inspired by the John Lennon Yoko Ono thing of ‘War is over (if you want it ...)’," the artist says. "They put up these posters, not just in America but overseas as well trying to end the Vietnam War by an act of positive thinking. They put a lot of money into these huge billboards."

Next to the sheep today is the dodo, scowling below the revelation "Demons are the ghosts of extinct animals" and above the declaration "Extinction Rebellion". That’s Extinction Rebellion (XR) — the international climate change activist group begun in 2018. Toothfish has enthusiastically assimilated its messaging, quickly recognising a fellow traveller when it burst on to the scene, initially in the UK.

We’re being asked to think, but the message is clear enough now: "The war against nature is over"; "Demons are the ghosts of extinct animals"; "You are an animal". Shortly, the final poster of this set will go up, a human skull — grinning stupidly as they all do — below the word "Extinction".

Toothfish’s genesis both predated and anticipated XR and its concern that civilisation’s disconnect from nature is precipitating a sticky end. But he’s running hard beneath its banner now, supporting XR’s demands for truth and action around climate change.

"There are two more posters I am working on, they should be out very soon. One has David Attenborough on it, and it is basically ‘Join Extinction Rebellion’, much more forthright," he says.

On this evening, Toothfish is working alone, but it’s an "et al" thing, collaborators contributing to the art and the distribution.

"There are quite a few other people who I have collaborated with on Toothfish projects. So some of the artwork has been done by other artists. But they have been formatted to have the look. There is one main collaborator who has been really helpful over the years, in doing colour and formatting. So I do a lot of the artwork but not all of it."

"So this one was quite contentious when it came out originally, in 2011."

He’s talking about that cat poster.

"It was the answer to the first poster. So the question is, by [the sheep] one, ‘Is there a war on nature?’, and if so, which side are you on? This poster intends to make it clear that we are all animals, so you need to be on the side of the animals."

Billsticking business Phantom was told not to put them up in Wellington and Dunedin.

"Some women don’t like it," Toothfish says. "But other women really like it because the breasts are really realistic. They are not like, perfect, you know? They are actually drawn off a friend of mine. I photographed her and drew her.

"It is also about the nipple wars. The idea that nipples are always censored in our society, female nipples. And, I think, not because of the sexual thing, it is because they remind us too much that we are animals. That’s my theory anyway."

Should we fail to come to terms with that, the outcome is certain, he says.

"Extinction. So, I see myself as a bit of an Old Testament prophet. Like the guy in the sack cloth going ‘The end is nigh’. It does not give me any pleasure to do it. But I feel somebody needs to do it."

If the cat poster got a rise, it was Toothfish’s full frontal assault on the poster boy of capitalism that really hit a nerve.

"Toothfish got its most visibility when the John Key poster came out," he says.

"I went towards John Key when he called us rent a crowd, at TPPA protests. I just got really angry when no-one questioned him on that. ‘What do you mean Prime Minister? Rent a crowd? Are you saying that somebody paid these people?’.

"He just seemed to get away with it."

Those posters went up directly in the public space, like all Toothfish’s art, punching up and sidestepping the editors and the censors.

"I believe that revolutions don’t happen on the internet," he says. "They happen on the street. So it is a way to go straight to the people that anyone can do. I am always surprised that there are not more people doing it. Why aren’t there more people out there putting up posters? Anyone can do it. What is it that is stopping people?"

Toothfish provides at least part of the answer himself.

"There is an element of risk doing this. I have been attacked doing this. I have had my camera stolen, threatened a number of times ... it’s not 100% safe."

Toothfish has finished with the shop window now, and moved on to an alleyway.

"I really like a nice composition where the whole thing becomes like one picture," he says, changing his mind and swapping a couple of posters around before the paste begins to set.

"In fact, I’m aiming a lot of these posters to hit people subliminally. I am not trying to tell people what to think. I am just trying to get them to engage. And they might not even notice they have seen the poster, you know? But if they walk past 10 of them it might sink in."

He’s happy to get feedback of all kinds, including vandalism.

"Interestingly, the one with the skull, some people really don’t like that. There have been some people who have actually been ripping off the word extinction. Which is great: I love it when things like that happen. And there have been other people writing on it, ironic comments. But that’s great. I love it. "

Toothfish calls his characters vengeful gods of nature. But talks about them with a great deal of affection. The sheep, the cat, the chicken, the fox, they’ve been chosen because he likes them.

"I have painted a lot of people’s pet chickens," he says. ... "They are beautiful animals."

His own nomme de art fits in here, Toothfish. As his website says: "Toothfish are also a species of deep water fish which live in the Southern Ocean and around the continent of Antarctica ... These lucrative fish are the basis of a risky fishery which threatens the health of the most pristine ocean on the planet — the Ross Sea".

The final poster to go up on this section of George St tonight is the fox, the trickster, staring enigmatically from the wall.

It has a message: "There is no God but me". Though it is all written in capitals. So, perhaps that should be: "There is no god but me".

The latter is more challenging. It allows no other god. The former simply upsets monotheism’s particular prejudices.

These are possibilities but there will be others. The viewer must bring what they can to this artwork, as the artist will be long gone, a trickster himself.