Wayne Kramer helped pave the way for punk rock, but paid a high cost for surfing on the edge of music’s new wave.

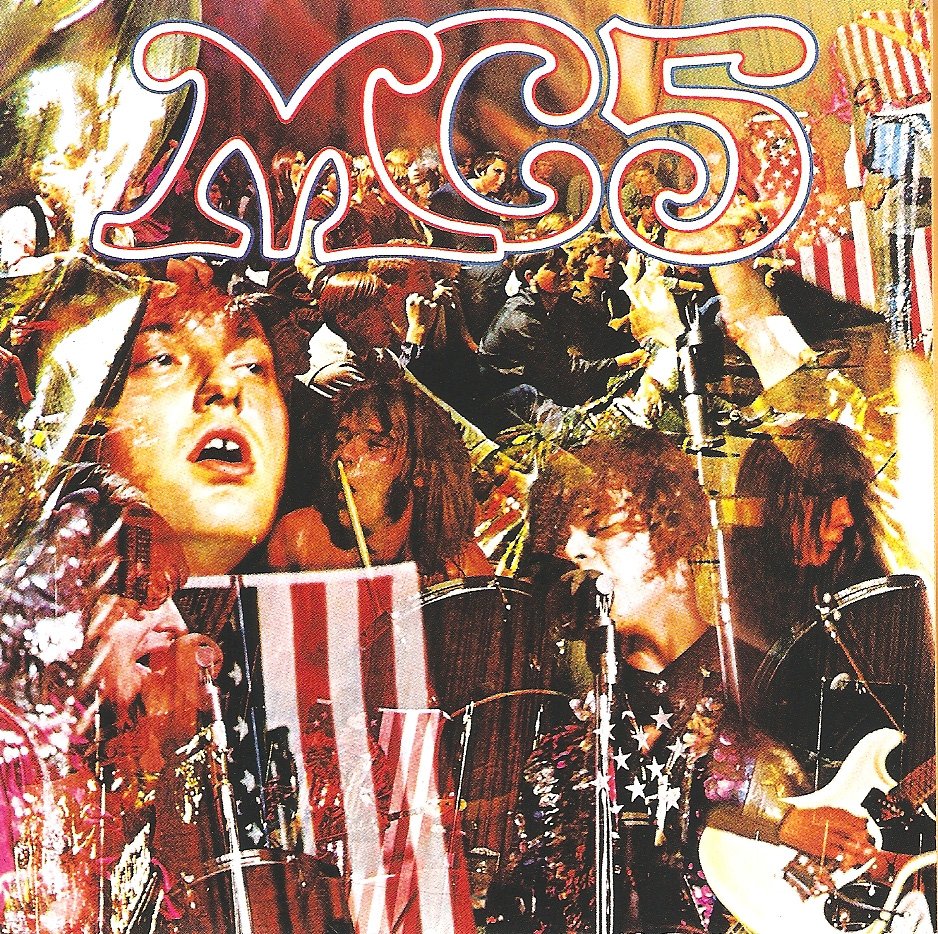

Raw and uncompromising, Kramer’s band MC5 did not sell a lot of records but they caused a whole heap of trouble.

Kramer spiralled out of control after the breakup of the band, but ended up rehabilitating and resurrecting himself as a punk pioneer revered by new generations of musicians.

Born Wayne Stanley Kambes in Detroit in 1948, his parents divorced at an early age and he suffered at the hands of an abusive step-father.

Music was his escape and the medium through which he met Fred "Sonic" Smith, his future MC5 bandmate.

The friends were in separate bands but both wanted to make music that was faster, heavier, harder and more political than anything anyone else was making at the time.

MC5 was formed in 1963 and from an R&B and blues base they created their own speeded-up garage rock sound which was rare at the time and which a modern listener would immediately classify as sounding like what in the 1970s was to become known as punk.

At the vanguard of both the musical and political shift was the twin guitar attack of Smith and Kramer.

As well as innovating musically, under the influence of manager John Sinclair (a co-founder of the White Panther movement) they espoused politics which put MC5 well out in front of the counter culture emerging in the United States in the late ’60s.

The MC5 was more radical politically than most of their peers and otherwise louder and more daring.

They were virtually the only band to perform during the infamous 1968 Democratic National Convention concert, in Chicago, where police were beating up anti-war protesters.

While attracting attention to MC5, their activities also attracted notoriety.

Sinclair had been Kramer’s entree to the worlds of jazz and poetry — fields in which he would later excel — and the two men remained close friends.

A live album of the same name reached the top 40 in 1969, their highest-charting release.

They also released the studio albums Back in the USA and High Time before breaking up at the end of 1972.

Kramer battled to ground himself after MC5 and became, in his own words, "a small-time Detroit criminal". In 1975 he followed in Sinclair’s footsteps and was convicted of selling drugs to an undercover police officer.

During his four years in jail, Kramer played in a prison band. He later became a leading figure in the charity Jail Guitar Doors, which provides musical instruments and lessons to inmates.

After his release Kramer mixed session work with playing in bands such as Was (Not Was), Pere Ubu and GG Allin.

Kramer faded from the spotlight in the 1980s, working as a carpenter, but the deaths of MC5 lead singer Rob Tyne (1991) and then Smith (1994) propelled Kramer back to music.

In the mid-’90s he began releasing music again as a solo artist, signed to punk label Epitaph Records, and in 2001 he formed a supergroup to perform MC5 music, which included The Cult’s Ian Astbury, The Damned’s Dave Vanian and Motorhead’s Lemmy.

His output wasn’t all hard rock though: in 2014 Kramer released a free jazz album, Lexington, which reached the top 10 of the jazz charts.

But MC5 kept calling, and various interpretations of the band toured, including a 50th anniversary lineup which featured the likes of Kim Thayil and Matt Cameron (Soundgarden) and Brendan Canty (Fugazi).

When not on the road Kramer delved into a new endeavour, working on the scores of films such as Talledega Nights and Step Brothers (2008), as well as several HBO documentaries. He also wrote a well-received memoir, The Hard Stuff.

At the time of his death Kramer was planning a world tour for the latest incarnation of the MC5 and had recorded new music to accompany it with the likes of Guns ‘n Roses guitarist Slash, Tom Morello of Rage Against The Machine, and Vernon Reid of Living Colour.

However, Kramer had been diagnosed with pancreatic cancer and died on February 2 aged 75. — Agencies