It has been a generous year for celestial distractions.

September’s solar eclipse provided that peculiar mix of communal excitement and individual absurdity: grown adults standing in paddocks and carparks, peering through odd-looking eyewear, united by a shadow moving at several thousand kilometres an hour.

Yet the project that gave me the deepest satisfaction this year was, I freely admit, an unapologetically nerdy one.

I was honoured to be invited to take part in "Circumnavigation in Time", an international art-science collaboration involving just 24 participants worldwide — one in each time zone. The organisers, a group of delightfully mad Czech scientists and artists, sent each of us a small black box containing a pinhole camera.

These boxes had minds of their own. At apparently random moments, shutters opened and closed, silently and autonomously, as the Earth turned.

My first attempt, between January and May this year, was set up in my office at the Museum.

The resulting image was mostly trees and regret.

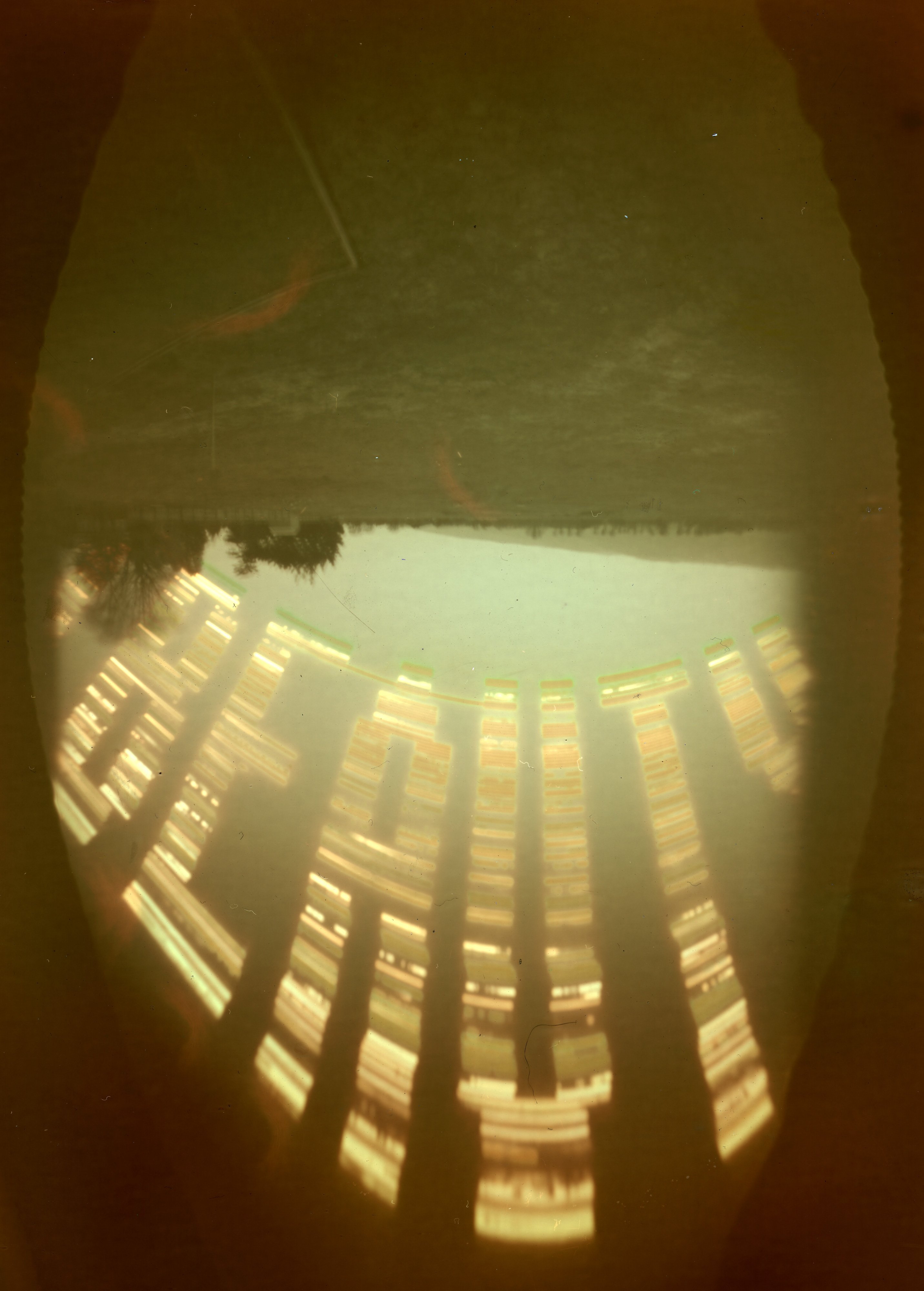

Undeterred, I mounted the box on my new observing shed in a Middlemarch paddock, where it sat patiently from July to November, accumulating light day-by-day, moment-by-moment, without complaint.

When I finally opened the box and scanned the image, the result was a delicate, ghostly record of the Sun’s passage through time and space.

A message, quite literally written in light.

It reminded me that there is still beauty in the universe — and that by working together, across borders and time zones, we can still reveal it.

This feels worth remembering in an era when parts of the free world are led by people who wouldn’t recognise beauty if it knocked on the Oval Office door.

May you all find reasons to look up, slow down and notice the light in 2026.