A controversial new book argues New Zealand should not have fought in World War 2 and may not have been fighting on the side of the angels.

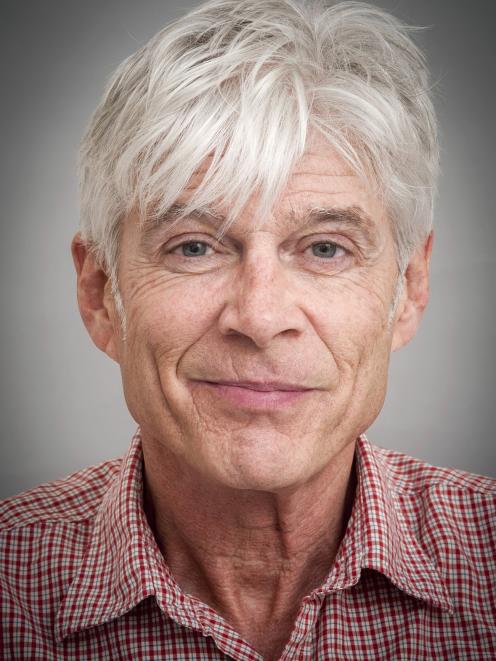

Bruce Munro talks to Stevan Eldred-Grigg about his quest to get Kiwis to ask tough questions about war.

"Dominion airmen, meanwhile, were up in the sky dropping bombs on Germany,'' Stevan Eldred-Grigg writes in his new book Phoney Wars.

"The policy of strategic bombing was swapped by the end of 1940 for a more frankly murderous policy called 'area bombing'.

"Air fleets no longer sought strategic targets but instead bombed city centres or suburbs. The New Zealand squadron started by dropping explosives on to streets of civilian housing in Mannheim...

"New Zealand households heard over and over again how pluckily the people of Britain were behaving under the bombings... Nobody told the households of the dominion that German civilians were also coping pluckily.

"Air raids after several months were killing far more civilians in Germany than in Britain yet the news media in the dominion stayed eerily silent about their suffering.''

It is historical fact. Little-known, but factual all the same. Laced, however, with emotive adjectives carefully selected and deliberately placed by the author.

Historians, it appears, are stuck between a rock and a hard place; between a hunger to share their knowledge and a desire to cultivate a hunger for knowledge.

Eldred-Grigg is speaking by phone from Wellington.

He is answering questions about his latest book Phoney Wars: New Zealand Society in the Second World War, which is hot off the Otago University Press. It promises to be just as controversial as its older sibling The Great Wrong War: New Zealand Society in World War 1.

Phoney Wars is the readily readable, 427-page, illustrated, footnoted and indexed culmination of five years of researching, mulling and writing on why New Zealand went to war, whether it should have fought, how New Zealanders felt about it at the time and the impact of this country's involvement in the war.

In it Eldred-Grigg, and his co-author son Hugh Eldred-Grigg, question the fundamental notionWorld War 2 was a battle between the "good'' Allied forces and the "evil'' Axis powers. They point to atrocities and failures by Allied leaders and troops, suggest New Zealanders were divided over whether to fight, and prod forcefully at the idea the country even really needed to take part.

"The Second World War is probably seen by nearly everyone, in our part of the world anyway, as an unquestionably justifiable war,'' Eldred-Grigg sen says.

"I wanted to tackle that question, and to get us to ask, and keep asking, questions about why we got involved.''

Although the Axis powers were "very unattractive, brutal regimes'', atrocities by Allied countries before and during the war were "sometimes as bad as the system our supposed enemies were imposing on people. And we don't often discuss that'', he says.

"In my opinion, all of the pain was unnecessary. There was no convincing reason for us to get involved in the war in the first place and no convincing reason to stay in the war.''

It is likely that at first glance, Phoney Wars may appear to many readers a massive betrayal.

Of course, war is not pretty. Of course, unfortunate things are done on both sides. Where is the value in focusing on the bad stuff when World War 2 was so clearly a worldwide battle against malevolent aggressors? Surely, digging for dirt is uncalled for; an act of treachery against all New Zealanders who suffered and lost their lives during the war.

POLARISING WORKS

IT IS NOT an accusation Eldred-Grigg is unfamiliar with. In 2010, The Great Wrong War polarised readers. Some congratulated him for setting the record straight. Others accused him of betraying his country.

He was surprised by the "betrayer'' label then, but thinks it is possible Phoney Wars will see him tarred with it again now.

He is not fazed.

"My opinion about it is that there is no such thing as a country. So, an historian has loyalty to the truth, not a country.''

The job of the historian is to get us all to ask questions and to take absolutely nothing at face value, Eldred-Grigg says.

"War is the worst thing humans do to other humans. The onus on us to look at them very closely and very sceptically is very heavy.

"So, we mustn't believe what we are told about wars. We must always keep asking questions about wars.

"And we haven't. We in New Zealand haven't, on the whole, asked questions about the Second World War.''

Eldred-Grigg was raised in a both-sides-of-the-tracks Christchurch family. His mother's family were proudly working class and defiantly sceptical about both world wars.

"My grandmother, Barbara Hall, personified that scepticism. She had a very sharp tongue and a very quick wit.

"My mother, to her dying day, was very good at doing an imitation of Winston Churchill: and it was not flattering.''

In contrast, his father was from conservative farming stock, which held rather different views.

Phoney Wars, he says, represents both the scepticism and the contrasts of his upbringing.

"Growing up ... made me very aware from babyhood that there were different ways of looking at New Zealand, even within Pakeha New Zealand.

"I grew up in a family where we talked about these things and thought about these things. You were allowed to think anything you liked rather than there being an official opinion imposed on us.''

Eldred-Grigg is not a pacifist. Nor is he defending Axis barbarism. But it is impossible to weigh one side against the other if you refuse to look at wrongs on both sides, he says.

Most New Zealanders are aware of the atrocious treatment of Jews, gypsies and homosexuals by the Nazi Government. And most know about the terrible treatment of prisoners of war by the Japanese military.

But few New Zealanders know of the way the British imperial government in India starved several million Indian people in Bengal in order to feed the British war machine, Eldred-Grigg says.

In 1943, when the Bengal famine broke out as a result of British policy, the New Zealand Government decided to send shipments of condensed milk to Bengal to help feed people and Canada decided to send a shipment of wheat. But Churchill vetoed it, saying the shipping was needed for the war effort.

"We and the Canadian Government could have insisted on prioritising the saving of lives in Bengal, but we didn't.

"Almost as many people were killed in the Bengal famine as died in the Nazi death camps. Three to four million. And it was absolutely in order to make the British war machine operate more efficiently by starving the villagers.

"That's one kind of atrocity that really needs the light shone on it.''

Another, Eldred-Grigg says, was the carpet bombing of German civilians.

"If you say 'Blitz' to most New Zealanders, they think of bombs dropping on Great Britain. They don't think of our air crews droning in their bombers over the cities of Germany, emptying their bomb bays on to villages and cottages and suburbs in German cities, unnecessarily killing many tens of thousands of people.''

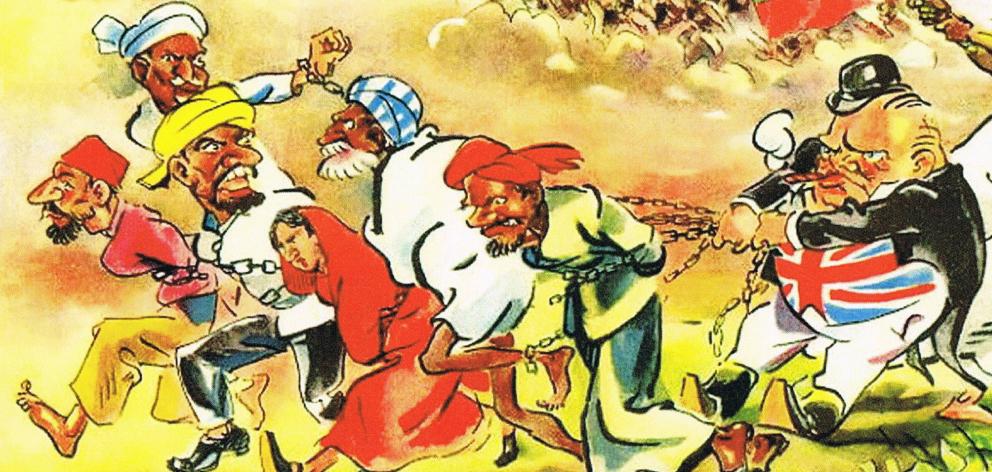

Comparing conditions in Allied countries with those in nations subjugated by Axis powers ignores the less rosy Allied treatment of people in its colonies, he says.

In fact, Hitler was very impressed by the way the British controlled India.

"A very big country with a far larger population than Britain, which it effectively controlled and milked for money''.

Hitler's real end goal in the war in Europe, Eldred-Grigg says, was to take over the Soviet Union and run it like Britain did India.

SHOULD NZ HAVE BEEN INVOLVED?

TODAY, most New Zealanders believe the unprovoked Japanese attack on Pearl Harbour brought it and the United States into World War 2. That is not the view of most historians now, nor was it the view of chunks of the public at the time, he says.

When New Zealand responded to the Hawaii attack by declaring war on Japan, despite media censorship, The New Zealand Herald said in an editorial responsibility for the war with Japan rested with US president Franklin Roosevelt, and to a lesser degree Winston Churchill.

"Most historians of the Second World War would now argue that Japan had been pushed into a very tight corner, primarily by a United States strategy,'' Eldred-Grigg says.

"Roosevelt wanted a war with Japan and was working very hard to get one. The New Zealand Herald saw that and said it.''

The Allied leaders were partially culpable and had innocent blood on their hands.

New Zealand need not have had any part in that, he argues.

Or, sort of argues. He also wants to ask the questions, present the information and let people make up their own minds.

"Why were we involved in the Second World War in the first place? Why did we stay involved? Why did we get involved the way we did get involved? Were there other options? Should we have changed the way we were involved once we discovered the cost in terms of money and above all lives?''

There were only two areas where New Zealand made a significant military contribution. Neither made any difference to the outcome of the war, Eldred-Grigg says.

"New Zealanders made up a significant part of RAF bombing squadrons. The bombing of German infrastructure almost certainly shortened the war, but unfortunately the great bulk of the payload of the bombs was dropped on houses rather than factories and railways. So, the one area in which we were most effective was in what wartime German propaganda accurately called 'terror bombing'. So, it was bombing of no military use at all except terrorising civilian people.''

The other was in the sideshow called North Africa.

"It wasn't crucial. The real war, in Europe, was the war between Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union.

"New Zealand played virtually no role in that war at all. It was the Soviet Union that ground down Nazi Germany.''

If New Zealand had wanted usefully to right wrongs it should have focused in its own Pacific backyard.

"I'm not a Christian, but the idea that charity begins at home is a compelling one. We had pressing issues closer to home we could have been trying to sort out, such as imperialism in the Pacific. People in the European colonies in the Pacific were being systematically conscripted for forced labour; what we were doing to the people of Nauru, strip-mining Nauru, was appalling; we continued to keep hold of Samoa against the wishes of its people.

"There were lots of issues of injustice in our own backyard. Why were we going off on some Quixotic crusade to Europe?

"We couldn't stop Nazi Germany, but we could be of some use in our own neighbourhood without going to war.''

What is forgotten, or is not known, is that not getting involved was an option. It was an option that some other countries choose and which a good number of New Zealanders at the time thought the Government should have chosen, he says.

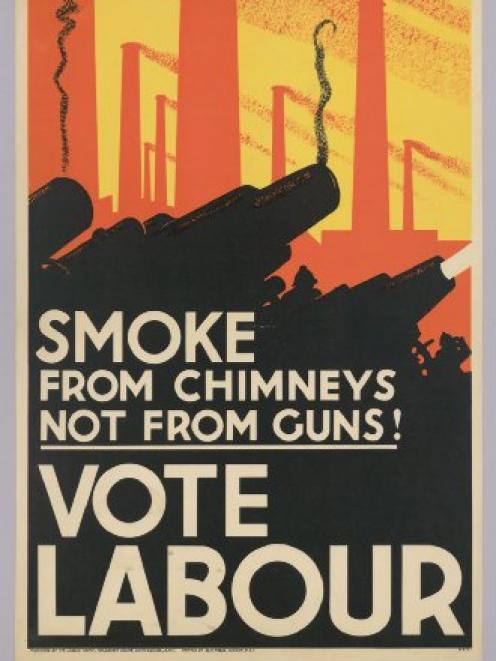

Labour governments around the world had a strong pacifist tradition. In New Zealand, it was epitomised by Dunedin-born MP John A Lee. So, it was a surprise when this country's Labour Government immediately jumped into the war.

'WAR FOR RICH TO BE FOUGHT BY POOR'

TO GAUGE how ordinary citizens felt, Eldred-Grigg not only looked at newspapers and diaries but turned to a little-used historical source, literary fiction.

"I did a lot of reading of novels and poems from during and immediately after the war to find out what people's feelings were, beyond what official documents told us about this.

"A lot of the unskilled working people saw it as a war for the rich to be fought by the poor.''

Most of the countries of the Americas, apart from Canada, stayed out of the war until their own interests were at risk.

Canada took a week to decide to go to war. South Africa took many weeks and only got involved in a limited way. Ireland declared neutrality and held their line despite enormous pressure from Britain.

If New Zealand had declared itself neutral, Britain would have made it pay an economic price. But that could have been an opportunity to cut the apron strings with Mother England, rather than being forced to a generation later, Eldred-Grigg says.

If neutrality had been a step too far, the country could have chosen limited involvement, as it did in the 1960s when faced with US pressure to take part in the Vietnam War.

"In the Vietnam War, we were under intense pressure from a very powerful and rather overbearing ally to get involved in a war in which our own interests were not at stake.

"Ironically, a National government, the Holyoake government, was very skilful and quite sophisticated in involving itself only slowly and minimally. It did a very good job of keeping Washington sweet, killing very few of our young men and doing almost no damage to our economy.

"While in the Second World War, our Labour Government did quite a bad job of protecting New Zealand's interests and killed many thousands of our young men.''

In the end, Phoney Wars was written with input from both father and son, Stevan and Hugh. A complementarity of the father's vivid writing to show what happened and the son's analytical input to explain events.

But the book's origin lay with the father in his upbringing and then, a decade ago, in a discussion with a friend.

The friends were puzzled and then concerned about the growing popularity of Anzac Day parades. Eldred-Grigg decided to investigate and The Great Wrong War and Phoney Wars were conceived.

He remains concerned about Anzac Day.

"Historians like the idea of people looking back at the past, and asking questions and saying 'why, how, what?' I don't think those questions are being asked now on Anzac Day.''

In the past, people had lived through war and so the parades were occasions of genuine mourning.

"Now, it is sentimentalised. It is a nostalgia industry.

"Now, we are finding large numbers of young people who are being socially engineered to be sentimental and nostalgic about the war, and not to ask hard questions about why we were involved,

"I think it is dangerous because it creates a social climate in which war is regarded sentimentally, rather than what it is, which is nasty, vicious and usually avoidable.''

Phoney Wars was written to counter that lack of analysis and insight, Eldred-Grigg says.

"I'm hoping that will be the impact, that more of us will think about the Second World War in a less knee-jerk and more adult way.''

So, was New Zealand on the side of the angels or the side of the devils?

It is difficult, when you want people to think for themselves but you have done a lot of thinking about the subject yourself, to resist the temptation to tell them what to think. Having hunted hard and long for the missing puzzle piece, do you eagerly display the completed picture to what may turn out to be a disinterested audience or hold back that final piece in order to whet their appetite for their own quest?

"Of course there were no angels and no devils,'' Eldred-Grigg says.

"Not even Hitler was a devil, although he came pretty close. And Churchill was certainly no angel. And nor was Peter Fraser, our Prime Minister for most of the war. An admirable man but with serious limitations, like all of us.''

He continues.

"We were on the side of the world of humanity: making bad decisions often and sometimes good decisions.''

But then, he checks himself.

"I don't have a final conclusion,'' he says.

"The book ends in an open-ended way, inviting people to ask questions for themselves.

"That's really what any historian wants. Historians don't want to tell you what to think; they want to suggest to you that you should think.''