The most visible reminder of the destruction of the 2010-11 earthquakes is the ruined Christchurch Cathedral, the focal point of Christchurch’s historic city centre.

While the debate about the Cathedral raged, other damaged buildings were restored, and new buildings - such as the celebrated ‘‘Cardboard Cathedral’’ - appeared in the precinct comprising Cathedral Square and the second Christchurch square to be named after a Protestant martyr, in this case Hugh Latimer.

This route also takes in some of the the city’s more important cultural and social sites: Turanga (the new Christchurch Central Library), the Isaac Theatre Royal and Takaro a Poi, the Margaret Mahy Playground.

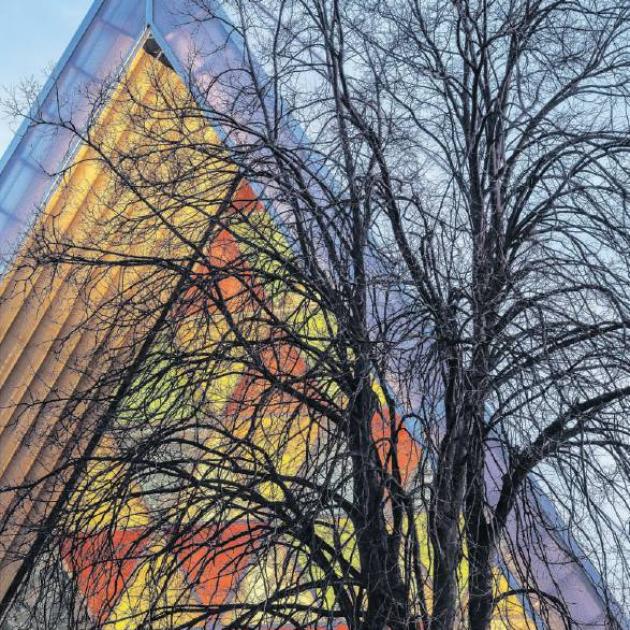

‘‘Cardboard Cathedral’’ 234 Hereford St Shigeru Ban, with Warren and Mahoney Architects, 2013

The genesis of the Christchurch Transitional or ‘‘Cardboard Cathedral’’ was so serendipitous that the theistically inclined might call it miraculous.

Shortly after the February 2011 earthquake wrecked Christchurch Cathedral, local Anglican cleric Craig Dixon came across an article about the Japanese architect Shigeru Ban, famous for his design of emergency structures, and then contacted Ban asking what he would charge to design a temporary cathedral in Christchurch. And so it came to pass that Christchurch now has the only building in New Zealand designed - for no fee - by a winner of international architecture’s top personal award, the Pritzker Prize.

Of course, the story of the building’s realisation was not quite so straightforward, but the project was characterised throughout by goodwill and collegiality, qualities notably absent from the debate about the fate of the ‘‘real’’ Anglican cathedral.

The article that caught Rev Dixon’s attention focused on a temporary church, made of paper tubes, that Ban had designed in Kobe after the 1995 Great Hanshin earthquake. Ban proposed a similar, although larger, building for Christchurch, but modified the structural design to accommodate local manufacturing capabilities and the church’s escalation of the projected life of the‘‘temporary’’ 700-seat cathedral from 10 to 50 years.

This is a deceptively sophisticated building. The structure’s 98 6m-long cardboard tubes are reinforced by timber beams and steel bracing. Up top, a polycarbonate roof twists into hyperbolic paraboloids; underneath, a 900mm concrete raft protects against ground liquefaction. Forty-nine translucent coloured panels designed by Ban and his colleague Yoshie Narimatsu illuminate the dramatic, triangular main facade.

After the September 2010 earthquake, a damaging but less destructive event than the ’quake of February 2011, the city council asked the public for ideas to inform the development of a central city recovery plan.

More than 100,000 suggestions were submitted, and the strong desire for a ‘‘greener’’, more accessible and more engaging city found expression in the plan. A few months later, the plan was redundant and the consultative process that shaped it was replaced by a top-down planning regime imposed by central government via the Canterbury Earthquake Recovery Authority (Cera).

The new direction for Christchurch redevelopment was set out in a ‘‘blueprint’’, produced to meet a 100-day Cera deadline, that compressed the size of the CBD, thereby protecting property values - post-earthquake demolition was leaving a lot of empty lots - and divided the city into precincts centred on ‘‘anchor’’ projects.

One development sector is the ‘‘East Frame’’, which was assigned the function ‘‘play’’, and its anchor project is the 1.6-hectare playground sited between Armagh St and a stretch of the Avon River.

‘‘Deliberate but managed risk’’ was the concept for the ‘‘all ages, all abilities’’ Margaret Mahy Family Playground, which was designed by Opus International Consultants (et al.) and named for the noted New Zealand author of children’s books. The facility is popular, and it also did its bit for the property sector: the playground cost $3 million; the land it occupies, $20 million.

New Regent St Henry Francis Willis, 1932, Historic Place Category 1

In an architecturally serious city in which the bar was set early, and high, by Benjamin Mountfort’s High Victorian Gothic Revivalism, New Regent St is a surprising incidence of design levity.

Along its 100m length, the street is lined with two-storeyed, pastel-coloured terraced shops, alternately topped by a curly gable or a straight-edged canopy. It looks make-believe - a film set, perhaps, or a piece of townscape conceived by Disney imagineers.

This fantastical quality is not accidental. The designer of New Regent St was Henry Francis Willis (1892/93-1972), a Christchurch architect who specialised in cinemas. Willis brought his theatrical sensibility to the design of New Regent St, and also a determination to give the project, which was developed as a kind of outdoor mall with 40 shops, a unifying coherence.

These impulses combined in Willis’ stylistic treatment of New Regent St. He opted for Spanish Mission, which, after having been deployed sparingly for 20 years in New Zealand, enjoyed a sudden vogue, especially in Napier and Hasting as those cities were rebuilt after the 1931 earthquake.

There’s something sunny about the Spanish Mission style (it came from California, after all): in the midst of the Depression, it promised the welcome escapism of a movie from Hollywood. After the 2011 earthquake, Fulton Ross Team Architects directed the street’s restoration (2013).

The Theatre Royal is the third incarnation of a theatre of this name on Gloucester St and the second on this site.

It was commissioned from the Australian-born and trained Luttrell brothers, Alfred (1865-1924), who was the designer in the family, and Sidney (1872-1932), who supervised construction and dealt with clients. In this case, the client was a syndicate, headed by American actor and impresario James Cassius Williamson (1845-1913), that owned a chain of theatres in Australia and New Zealand. The Theatre Royal was retro, even in 1908: the Luttrell brothers took a form-advertises-function approach and styled the building in a theatrical Victorian manner.

In the late 1920s, the building was turned into a cinema, but in the 1950s it once more became a performance venue, serving up, for several decades, a democratic bill of fare - operas, ballets, concerts, wrestling matches, magic shows.

A public campaign saved the building from demolition in the late 1970s and it was restored as a working theatre in 2004-05 and again, far more substantially, after the 2010 and 2011 earthquakes (Warren and Mahoney Architects, lead architect Richard McGowan, 2014).

A feature of the Rococo interior of the theatre, which now bears the name of civic benefactor Diana Isaac (1921-2012), is the dome with its original decoration - scenes from A Midsummer Night’s Dream, painted by G. C. Post of Wellington’s Carrara Ceiling Company, channelling his inner Tiepolo.

In the first years of post-earthquake reconstruction, there was considerable global interest in the questions of what form the new Christchurch central city might take and what sort of architecture might emerge on the tabula rasa of bulldozed city blocks.

It seemed that this interest, and a steady parade of overseas experts, would yield a crop of buildings designed by international practices, and that a relatively parochial city could take on, for better or worse, a cosmopolitan architectural character.

But this did not happen; apart from Shigeru Ban, whose presence was the result of peculiar circumstances, the only exotic architectural practice to have been involved in a major Christchurch recovery project is Schmidt Hammer Lassen Architects.

The Danish firm is a world-leader in library architecture and, in partnership with Architectus and the Matapopore Trust, which represents local iwi Ngai Tahu and hapu Ngai Tuahuriri, it designed Turanga, the central Christchurch library.

The anchor building is a five-storey civic marker on an important site that, pre-earthquake, was shared, in desultory fashion, by God (via Christchurch Cathedral) and Mammon (in the guise of various tourist traps).

Turanga is a milestone in the evolution of biculturalism in a city in which Anglocentrism has, at times, blurred into racial chauvinism.

The library acknowledges local iwi not only in its title - Turanga is the name of a Ngai Tahu ancestral settlement - but also through the realisation, most obvious in the library’s dramatic and generous central stairway, of the concept of whakamanuhiri, the welcoming or ‘‘bringing-in’’ of visitors.