Dare mention co-governance and a range of responses is provoked.

Towards one end is enthusiasm about possibilities flowing from a set-up aimed at promoting inclusive, holistic decision-making.

Towards the other is rhetoric about the looming "ethno state" and suspicion of a perceived agenda to undermine democracy.

In the mix are advocacy for taking the Treaty of Waitangi seriously, uncertainty about the implications of this, concern debate is being stifled and worries about the tenor of discussion as an election nears.

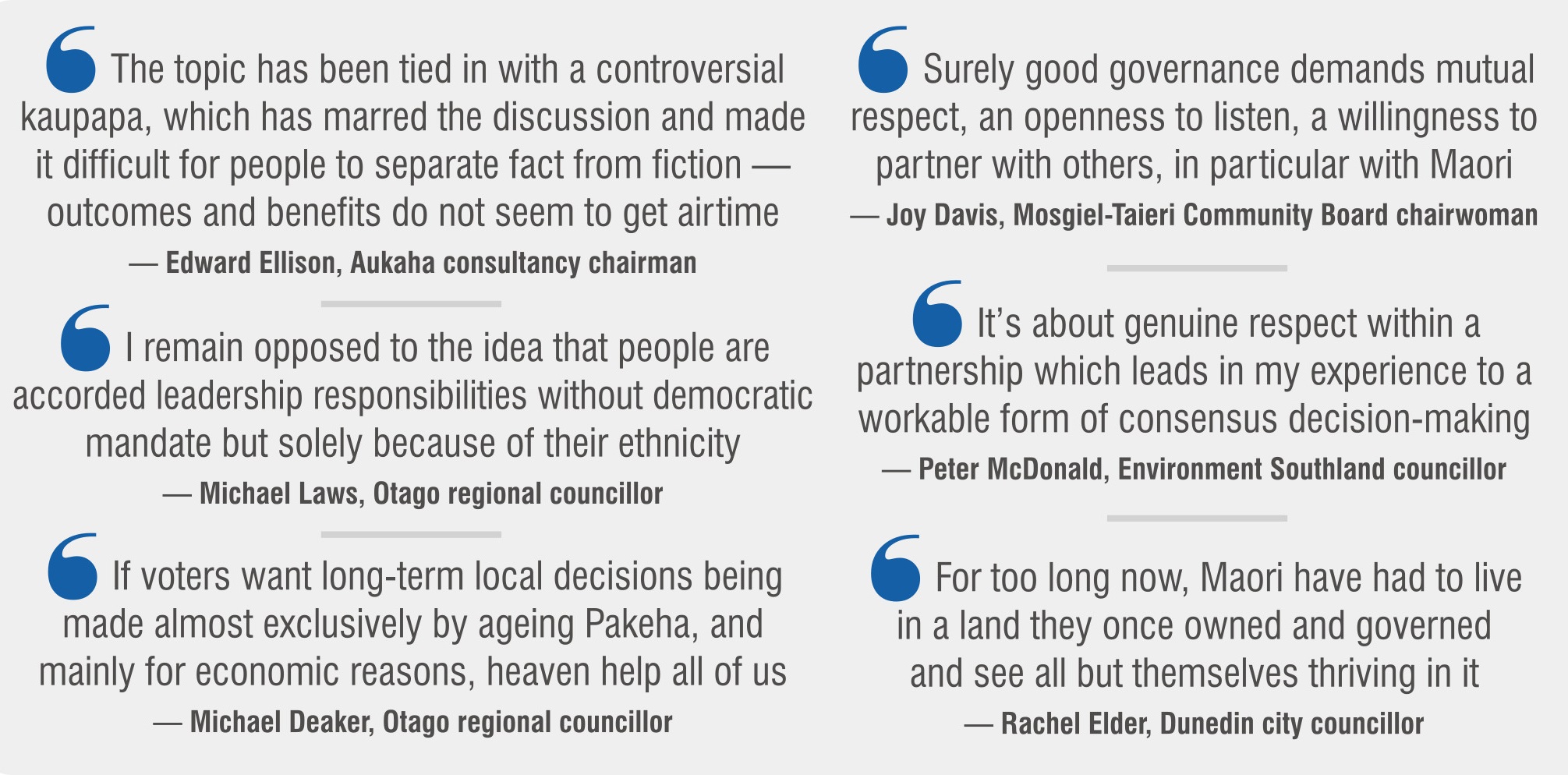

For Otago regional councillor Gretchen Robertson, co-governance has many meanings and recipes. Her experiences of co-governance and partnership have been positive.

For her colleague Hilary Calvert, there are issues "long before you get to the reality of what you mean by co-governance".

"Who has the casting vote? Is Parliament still in charge? Some seem to be suggesting equal say. How would that work?"

For Ngai Tahu, co-governance represents a basic idea — in some areas of policy, particularly the environment and managing natural resources, it makes sense for the Crown and its Treaty partner to work together as equals.

"It is not about an erosion of democracy, separatism, or any of the other accusations sometimes levelled at it," iwi representatives Edward and Matapura Ellison said in a joint statement.

"It’s about local communities, and people who care deeply for the land and water around them, helping get things on track."

Environment Southland councillor David Stevens, who is not seeking another term, is worried the community might not have adequate discussion about the issues before voting starts in local body elections next month.

"Co-governance is the elephant in the room and the sad situation is no-one wants to discuss, as they are ... often accused of racism if they have a different opinion."

What is co-governance?

Co-governance is typically described as an arrangement for negotiated decision-making between iwi and other groups, such as central and local government. It refers to input at the governance or strategic level, rather than day-to-day management.

It emerged in Treaty of Waitangi settlements and, as former Treaty Negotiations Minister Chris Finlayson has said, co-governance has been part of the landscape concerning natural resources, such as rivers, for some time.

As Mr Finlayson describes it, debate now is about the extent to which that could or should be extended.

Nationally, the subject has been contentious enough for

Act New Zealand to call for a referendum, arguing co-governance means "some representatives are democratically elected and others get a seat at the table because of who their ancestors were".

Co-governance is one contentious element of Three Waters reform, where it is proposed iwi will have a role in determining strategy for planned large water entities.

Environment Southland chairman Nicol Horrell suggested the national Three Waters controversy had been unhelpful.

"Partnerships which include aspects of co-governance ... work well where there is trust, respect and transparency between all parties," he said.

Regional councils are required by legislation to work with mana whenua to improve freshwater.

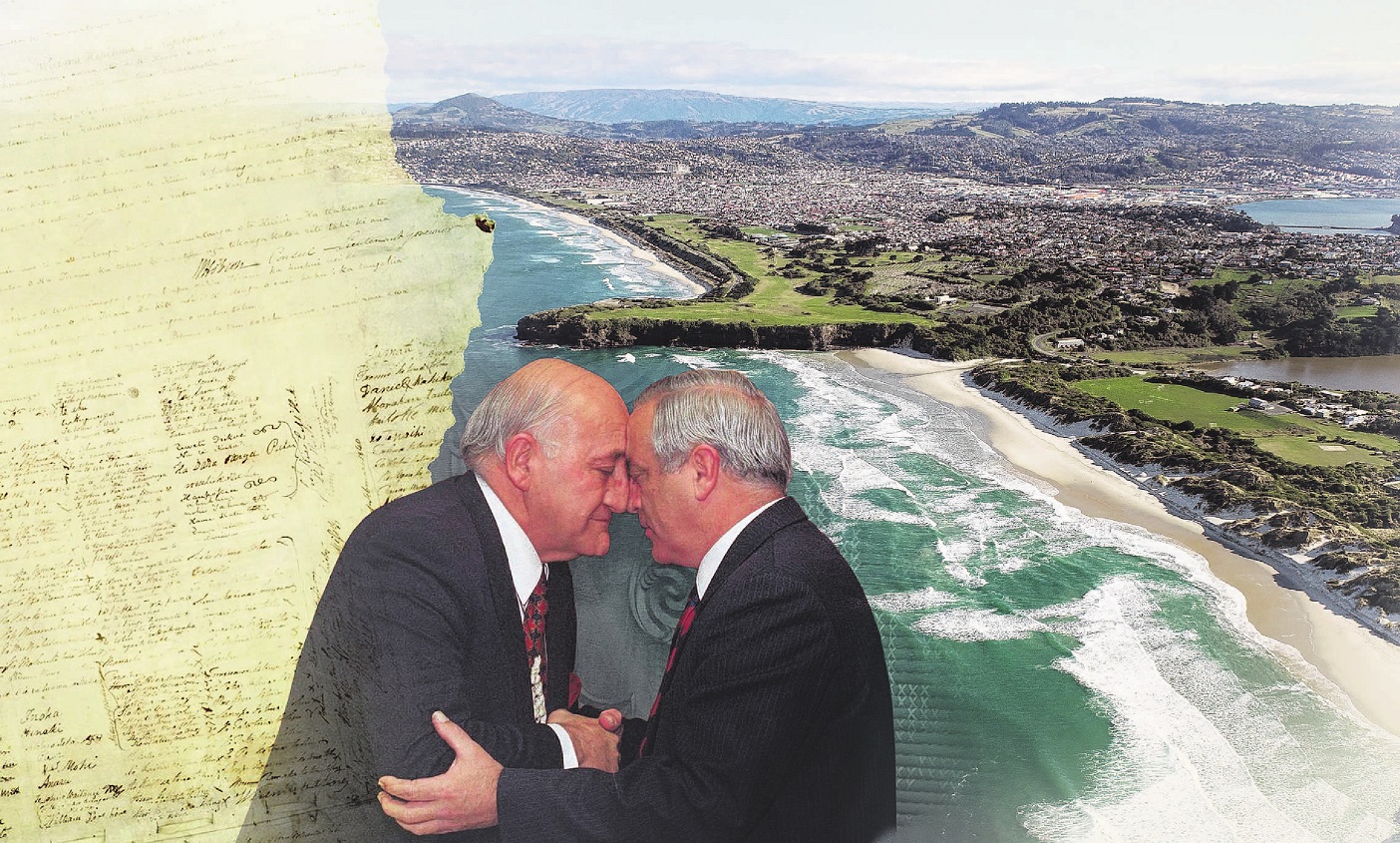

Otago Regional Council chairman Andrew Noone highlighted a partnership with mana whenua established in 2003.

"The partnership provides for increased participation of Kai Tahu in Otago’s environmental management — both parties are committed to working collaboratively in a structured and meaningful manner."

The Local Government Act 2002 makes clear councils should develop and maintain ways for Maori to contribute to decision-making. Councils are required to provide detail in their 10-year plans about how they will help build Maori capacity to contribute to decisions.

For Ngai Tahu, co-governance includes reconnecting iwi to taonga and providing expertise and knowledge in managing resources.

"Look at the state of freshwater in the South Island," the Ellisons, who are second cousins, said in their statement.

"It’s a disaster.

"So it’s not as if the Crown has had much success over the last two centuries.

"The Ngai Tahu view is that we can help provide the cleaner water and environment that all New Zealanders want."

Co-governance, sometimes called co-management, has become an increasingly common part of Treaty settlements in the past 20 years.

Back when Ngai Tahu settled its claim in the late 1990s, co-governance arrangements were not yet common.

The settlement contained one co-management agreement, enabling the iwi to work alongside local government to manage Waihora, Lake Ellesmere, in Canterbury.

Edward Ellison — who was prominent in Treaty negotiations, is chairman of the Aukaha consultancy and heads up the Otakou runanga — saw existing arrangements in Otago as being at the partnership level, rather than co-governance.

Mr Ellison said it was important to understand that the co-governance concept had a Treaty base.

The Crown’s actions in the past had been blatantly unfair, but it had in recent years engaged constructively in a bicultural path forward, he said.

He spoke of reversing shortcomings of local government and helping it to be responsive to its Tiriti o Waitangi obligations.

Iwi tended to enable a more holistic approach and that drove better outcomes for the environment.

Why the controversy?

Otago regional councillor Michael Laws said a constitutional revolution was under way to undermine the philosophy that traditionally underpinned representative democracy in New Zealand — one person, one vote.

He was one councillor who brought up He Puapua, a discussion document that essentially argues for more Maori self-determination but which has also been characterised as an unofficial blueprint for "breaking up New Zealand" along racial lines.

"Co-governance has been imposed as an almost direct consequence of the He Puapua thinkpiece initiated by Te Puni Kokiri," Cr Laws said.

"Neither the Treaty of Waitangi in 1840, nor the Court of Appeal judgements interpreting the ‘principles’ of the Treaty (in the late 1980s/early 1990s) flagged co-governance as a leadership device. That is a very modern artifice."

Dunedin city councillor Lee Vandervis called co-governance "the antidemocratic divisive sharing of power with unelected self-selected race-based tribal elites".

Invercargill deputy mayor Nobby Clark said he supported partnerships, but he was opposed to progression of He Puapua by stealth.

Counter-arguments

Cr Robertson said fear-mongering sprang from fear of the unknown.

Fellow Otago regional councillor Alexa Forbes said power structures had not suited "those who are not of Pakeha mindsets".

"We need to shape our democracy to suit our unique situation."

Otago political commentator Dr Morgan Godfery agrees with Cr Laws a constitutional revolution is in motion, but he has argued co-governance is orthodox Labour and National party policy.

Dunedin city councillor Steve Walker highlighted an example of co-governance that was set up in 2010.

"From what I’ve read about the Waikato River Authority, the co-governance board has led to extremely positive outcomes for the Waikato River’s restoration," Cr Walker said.

"I’d argue that from a purely governance perspective, it’s only wise and sensible to try and ensure that Maori voices are heard at the decision-making level."

Healthy debate

Cr Calvert raised concerns about groupthink, as it seemed diversity of views about the merits of co-governance was increasingly less welcome.

Dunedin city councillor Sophie Barker said debate should not be avoided, but it should be respectful.

"It’s harmful to truth and trust when people take reactionary stands on issues," Cr Barker said.

"I believe that there is a lack of understanding throughout the community of Treaty/Tiriti obligations of local government."

Outgoing Queenstown Lakes Mayor Jim Boult said debating important issues, including co-governance, should not automatically lead to racism or hateful speech.

"In fact, healthy and open debate should be encouraged, bad behaviour should be called out and we should be investing more time and effort as a nation in preparing our young folk to be willing and able to actively participate."

Opportunities?

Environment Southland councillor Robert Guyton said co-governance arrangements in a regional forum there had resulted in high-quality advice for improving water quality.

Dunedin Mayor Aaron Hawkins said he saw exciting opportunities to "make good on our commitments under Te Tiriti o Waitangi".

"This is the messy business of what it means to be a bicultural nation in practice. There will absolutely be differences of opinion in terms of what that looks like, among Maori and tauiwi.

"We just have to accept that we’re going to get it wrong sometimes, be prepared to learn from that experience, and build deeper connections as a result."

‘Rise above the use of divisive language’

The Human Rights Commission holds the position that New Zealanders should not fear the developing and strengthening of indigenous rights.

"There are different ideas, concepts and models that are discussed when the topic of co-governance is brought up," a spokesman said.

"Discussion around these concepts is both valid and important.

"However, it can be both unhelpful and counterproductive when groups of people are pitted against each other as we work towards an inclusive and cohesive society.

"We should rise above the use of divisive language and steer clear of stereotypes and sentiments that negatively frame whole communities.

"Honest and frank discussions around Te Tiriti o Waitangi and its history, and an openness to learn, are a must when holding responsible conversations."