Despite that, they believe that using water heated by Dunedin’s extinct volcano may be an idea whose time is coming.

John Gibb spoke to group member Dr Mike Palin about the group’s hopes and plans.

Scientists trying to unleash geothermal energy from deep under Dunedin have had a setback, but believe they still have a strong case for tapping into an extinct volcano.

Geologist Dr Mike Palin says there will be an opportunity lost and mismatch between policy and action, if a more sustainable heating source - such as geothermal energy - is not part of planning for the new Dunedin Hospital.

Dr Palin and a team of fellow researchers in the University of Otago geology department want to drill two 500m-deep test bore holes, one in central Dunedin and one in Portobello or Port Chalmers, to investigate if sufficient heat energy can be obtained from residual heat from extinct volcanoes deep under the city to heat water, and potentially power a new hospital, for example.

Dr Palin said there was a strong case for considering the potential use of geothermal energy.

"The Government is investing over a billion dollars on the new hospital complex," he said.

Because of climate change, reducing carbon emissions was also a high priority.

"Burning biomass for heating, as currently planned, is not the best alignment of policy and action," he said.

Climate change was happening much faster than previously thought, and human-generated carbon emissions should be cut to nearly zero within the next few decades.

He and his colleagues were asking if residual heat from extinct volcanoes could be used as a geothermal energy resource, thereby cutting use of carbon-based fuel and greenhouse gas emissions.

In Dunedin, the main users of heat were Dunedin Hospital, Otago University and the central business district.

Cutting fuel costs would help energy users directly, and would also generate indirect savings for the government through its funding of health services and tertiary education, he said.

The university and hospital already shared some steam-related heating.

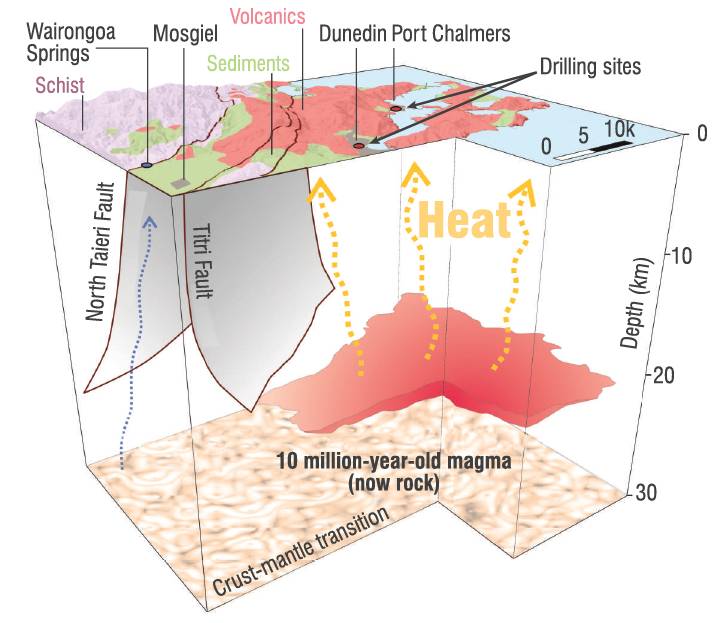

The team hoped to drill beneath the veneer of sedimentary rock to monitor any residual heat from the now solidified magma chamber that lay beneath.

If test results were positive, heat could be captured by pumping water underground in a loop and bringing it back heated—a potential world-first exploitation of heat from an extinct volcano.

Such drilling was "commonplace in mineral exploration" and had taken place across Otago for decades.

The team would continue consulting the local community, iwi, business and government, and carefully review feedback from the MBIE assessors when it was available.

The group would meet its partners and other interested parties to discuss options, including resubmitting its funding application later this year.

Dr Palin said the eroded Dunedin Volcano visible today represented "only the tip of the iceberg in terms of the ancient magma system".

Most of the magma - molten and semi-molten rock - was trapped below ground, where it cooled slowly and solidified as rock.

Available data suggested a large volume of warm volcanic rock was a few kilometres down, and there were "good reasons to be optimistic" that this was a good source of geothermal heat.

After hearing the term "geothermal", people often thought of "geysers and boiling hot springs in places like Taupo and Iceland".

"But geothermal is everywhere - the word literally means ‘earth heat’ and the interior of our planet is hot."

Iceland’s active volcanism and extremely high heat flow made it more like Taupo than Dunedin.

Nevertheless, Iceland had successfully used geothermal energy for many decades, also mainly to heat buildings, he said.

Dunedin Volcano

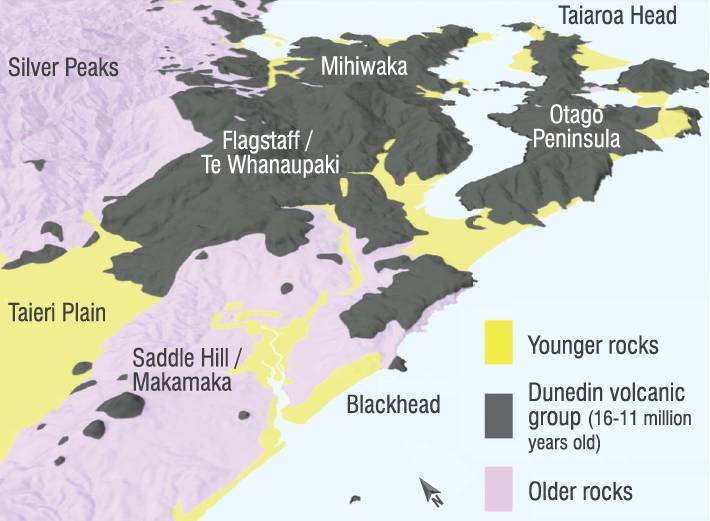

- Dunedin is home to an extinct, heavily eroded volcano that was active between about 16 million and 11 million years ago.

- Otago Harbour now fills some of the oldest parts of the volcano, which originally extended from central Dunedin to Aramoana, about 25km away.

- This compound volcano was partly formed from successive layers of basaltic lava, but also includes broken volcanic rock called tuff.

- Volcanic remnants now form hills around the harbour, including Mt Cargill, Signal Hill and Otago Peninsula.

- Although modern Dunedin does not look like Mt Taranaki, both are compound volcanoes.

- Dr Marco Brenna, of the University of Otago geology department, said a deeper volcanic plumbing system later matured and magma (molten rock underground) stalled in large chambers 10km-20km beneath the volcano. These slowly solidified, forming large bodies of hot rock, which were still cooling today, providing a potentially reliable source of clean energy.

- A volcanic mountain which had been built when activity ended 11 million years ago was slowly shaped, by extensive erosion and fault activity, into valleys and hills, including the harbour and peninsula.

Comments

If you had a go fund me entity (or such like) to contribute to I would gladly donate $1,000 to this project. Even if only for informative articles, blog pages or public lectures etc. like this, providing knowledge and feedback on learnings and results. It is really fascinating to learn about the forces that shaped the ground, beaches and rocky crags we walk, tramp and swim in daily. Wonderful work in a unique environment please keep it up.

In thanks Averil

Hi Averil-

Thanks for your enthusiastic response and desire to learn! I have heard similar comments from many people in recent years. We will try to find more opportunities to share knowledge within our community more regularly. We live in fascinating times and in a fantastic place!

Mike Palin